![]()

1 Introduction

Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster.

(Nietzsche, 2009)

Introduction

When de’ Medici ‘founded’ the first bank on the benches of the Florence market over 600 years ago (Ferguson, 2008), they could hardly imagine the role that financial institutions would play in the future, nor could it be inferred that financial institutions would become one of the big brothers of the twenty-first century, reporting their own clients to the authorities in case of suspicious transactions or attempted money laundering.

The role of banks in anti money laundering (AML), although inevitable in the battle against this type of crime because of their central and crucial position in financial markets, has taken the shape of an encompassing and above all very intrusive system. Surprisingly, criminology has given relatively little attention to this system since its emergence in the late 1980s. This is remarkable, not only for the extent of its invasion into personal spheres and the subsequent privacy issues that arise from it, but also for its immensity. After all, the AML system is – quietly – activated whenever a bank transaction is carried out, cash is deposited or bills are paid through online banking. Financial institutions, as gateways to the financial system, to economic power and possibilities, are considered to be one of the major vehicles for money laundering and therefore also represent an important means to prevent this type of crime. In the past ten years, the investment of this sector in the prevention of money laundering has been increasing rapidly.

Today, ‘compliance’ and ‘anti money laundering’ are terms that make part of a semi-universal language that has been developed since the late 1980s. After all, money laundering, the ‘process in which assets obtained or generated by criminal activity are moved or concealed to obscure their link with the crime’ (IMF, 2004), has increasingly received attention during the last twenty years, from both policy-makers and international organisations. This criminal phenomenon is depicted – first by the US, but quickly followed by the UK and Europe – as a major threat to society and its economy. As a result, the battle against money laundering has become an international concern and – as some claim – a convenient motive for policy-makers to implement far-reaching regulations and guidelines. Fighting money laundering is a national (cf. for Belgium see the National Security Plan of the Belgian Police, 2008–2011) and international priority (on the level of the European Union, the US and international bodies like the OECD and IMF) and has been so for over two decades. During this period, we have witnessed a growing apparatus of legislation, regulation and guidelines on an international level. This battle not only focuses on the prevention of money laundering as a crime in itself, but is also used as a means to identify the perpetrators of predicate crimes being the origin of the crime monies to be laundered.

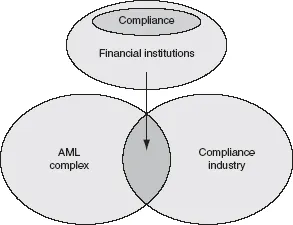

The input and effort that is demanded from public and private actors in the prevention and detection of money laundering is rather high (Commission of the European Communities, 2009). As a result of international and national initiatives that were taken in the fight against organised crime and money laundering, we are currently witnessing the development of two parallel angles around the fight against money laundering and its predicate crimes: a legislative, regulative angle, designed to prevent and detect money laundering on the one hand, and an intrinsic commercial position towards anti money laundering, stemming from a self-protecting reflex by financial institutions, aspiring to protect themselves against regulatory and reputational risks. These developments will be referred to respectively as the anti money laundering complex and the compliance industry. Between these separate and yet intertwined perspectives, we see private financial institutions, straddling both worlds. These private institutions are on the one hand a part of the AML complex, through the employment of inspectors who need to enable the institution to comply with the regulation: the compliance officers. On the other hand, however, these financial institutions purchase services from the – non-financial – compliance industry to support their implementation of AML measures, and are in this sense sponsors of the compliance industry.

The compliance officer, responsible for the implementation of AML legislation and reporting of potentially suspicious transactions, symbolises a part of this private investment in anti money laundering. As a bank employee, responsible for the implementation of governmental objectives, he finds himself trapped between crime-fighting objectives and commercial goals. The duality of the involvement of private partners in the AML complex and the vastness of the system induce a closer look at the functioning, values and perceptions of actors within this system. This was the starting point of my PhD study (2006–2009) which is embodied in this book.

Research questions

This research set itself the objective of gaining insight in the compliance function of financial institutions, based on the central hypothesis that the AML complex and the compliance industry are two parallel constructions, both working in the same domain, but on the basis of different objectives and motivations. These differences in motivation may not only result in differential attitudes and working methods, but also reveal the dilemmas that actors within AML are dealing with.

The AML complex consists of the activities of private and public actors, carrying out regulatory, monitoring, reporting, investigatory and judicial tasks. The objectives of the AML complex are prevention, crime fighting and law enforcement, and it is based on government regulation.

The compliance industry, on the other hand, is an entrepreneurial market providing services and tools in support of the fight against money laundering. This industry stimulates compliance and AML investments by providing monitoring systems, blacklists, training and advice to corporations that are obliged to implement the AML legislation. The compliance industry provides an additional service to AML regulation, in which AML compliance is marketed as a product for sale.

Financial institutions perform a pivotal role between these constructions, adding to and interacting with both the complex and the industry. As go-betweens, they are continuously looking for a balance between the interests that derive from each structure: commercially oriented – within an entrepreneurial environment – or crime fighting and prevention. Based on this dual role, the complex and industry were studied from exactly this viewpoint. Starting from the compliance function in Belgian financial institutions, we intended to answer three questions: (1) how do these constructions function; (2) which interactions do we see between both; and (3) how does the compliance function fit into this perspective?

Figure 1.1 AML complex–compliance industry.

At the start of this research, we hypothesised that within the AML complex adverse attitudes are present, as different actors with dissimilar backgrounds are united. The outsourcing of government tasks to the private sector results in a paradoxical role for financial institutions. After all, the financial institutions’ core business can clash with the monitoring task that is imposed by AML legislation; it is not always in a commercial interest to refuse customers or end client relationships. Looking into these potential contrasting interests can lead to an increased insight into the position of financial institutions and the norms they uphold, and to a view on the feasibility of imposing a surveillance function on private corporations. On the other hand, we also recognise interests that stimulate compliance within banks. Out of concern of risk management and foremost reputation protection, AML compliance can be encouraged. Regulatory sanctions also play a role in this respect, and serve as the stick in case of noncompliance.

The compliance officer bridges both worlds. In his/her role as inspector of employers, colleagues and clients, his function inherently implies a duality. The compliance officer is a relatively recent actor within AML; in Belgium this function was only implemented in 2001, as a result of a regulatory obligation. The compliance officer is therefore a new and recent profession that has some analogies with policing and private investigation. The compliance officer actually polices the money and determines the input of the AML chain, through his or her reporting duty to the FIU (Financial Intelligence Unit).

Research scope

In every research, choices need to be made and some paths cannot be taken. This allows for a detailed focus in research, but inevitably implies that certain areas will remain unstudied. In this research, we have defined the research scope by focusing on three domains. Our choices will be outlined shortly.

First of all, in an international sense, this study is limited to the Belgian compliance officer, working within the Belgian system. However, I am convinced that the issues which the Belgian compliance officers are confronted with, are quasi-universal. Compliance officers all over the world have to make judgements on a daily basis whether to report a client or not and have to analyse the extent to which a transaction can be considered as ‘normal’. Compliance officers all over the world are faced with the same dual position: working as a bank employee, but sometimes having to make decisions that may harm the bank in a commercial manner. This was also confirmed by research in other countries (for example Levi, 1997; Levi, 2001; Favarel-Garrigues et al., 2008; Harvey and Lau, 2009). Regardless of the specifics of the legislation, the bottom line is the same. Of course, differences in legal system and requirements for compliance officers exist and are sometimes crucial to the AML system. On the other hand, system problems are also discussed as universal. For example, feedback from the authorities to the private sector can be seen as minimal in most European countries, as shown by a recent study commissioned by the European Commission. The same study concluded that reporting institutions within Europe also question the efficiency and effectiveness of the system. This is partly due to the lack of transparency and know-how with regard to the outcome of AML policy (European Commission, 2008). The daily dilemmas may therefore very well be relatively convergent.

Second, in view of the AML reporting system, we must note that this study is limited to financial institutions, excluding other reporting institutions, based on both feasibility and their role within the AML approach. Although studying the reporting behaviour of other institutions would have been interesting, financial institutions were the first to institutionalise a formal compliance function for the AML task.1 Furthermore, within the reporting system, financial institutions not only report the highest sums to the FIU, their reports were also those that are most often sent to the public prosecutor's office (in 2005, almost 75 per cent of all reports to the public prosecution were based on reports by financial institutions (CTIF-CFI, 2006)). Banks therefore represent an important actor within AML. Today this finding still holds. In 2008, financial institutions reported 4,034 suspicious transactions to the FIU. Although financial institutions today make up only 21 per cent of all reports to the FIU (see Chapter 8), reports stemming from banks have the highest percentage of ‘subsequent reports’ that are sent by the FIU to the public prosecutor's office (64.7 per cent of all files), and are worth 79.3 per cent of the total amount of money that is considered as ‘criminal’ in all reports to the public prosecutor's office (CTIF-CFI, 2009). We assert that financial institutions are involved in the battle against money laundering in a threefold manner: first, they are a commercial institution, aiming to present themselves as reliable and trustworthy towards their stakeholders. This implies implementing solid AML and compliance policies to show the outside world that they are taking these matters seriously. Second, the financial institution also acts as an inspection agency, having to monitor and verify (trans)actions of their customers and employees. Financial institutions are put in a position that may lead to conflicts of interest (Naylor, 2007) between their obligations towards the authorities on the one hand and responsibilities towards clients on the other. And third, banks themselves are monitored by regulators as they are also potential offenders.

A third limitation to this research is the fact that compliance was narrowed down to anti money laundering. First of all, we must make clear that ‘compliance’ may refer to a number of initiatives taken by corporations to make sure that they are abiding rules (Hutter, 1997), which can relate to a broad area of regulations, such as environmental or labour issues. ‘Compliance’ in the present study, however, is used in a more strict sense and implies the implementation of the integrity policy within the financial institution, concentrated on the topic of money laundering. A compliance function within a bank combines, next to anti money laundering, also other domains, including for example privacy legislation and insider trading. Anti money laundering, however, not only represents the basis of the compliance function (through the Law of 11 January 1993) and still makes up for a large part of the daily activities of compliance officers (as was also confirmed during the interviews and in the survey), but also is the most relevant part of the compliance function to study from a criminological point of view. The AML task, after all, implies prevention and detection of a criminal activity, which in itself is of interest for criminologists. In this sense, obligations of compliance – or AML officers – have several similarities with policing. As part of their duty is to make sure the bank acts according to the rules, we witness the emergence of a type of ‘policing’ within a private organisation (‘policing the enterprise’, in other words). In this context, we also observe some parallels with private investigation services, operating within corporations to investigate fraud and crime by employees (Hoogenboom, 1988b; Cools, 1994). These parallels, combined with the specific position of the compliance officer within a bank, result in an intriguing function in which several interests are at stake.

Methodology

Phasing

In this four-year research we used a multimethodological approach (Ponsaers and Pauwels, 2002; Bijleveld, 2005), implying a combination of quantitative and qualitative traditions. Both methods are complementary and may provide supplementary data. This decision was based on two grounds: first of all, we were moving in a research domain that had not been subject to criminological research in Belgium before, and we therefore had to take into account that a large investment was needed in order to make a first exploration of the sector. Second, the combination of several methods seemed the most efficient way to deal with potential access problems.

Every research consists of a technical research plan (Billiet and Waege, 2003). This study was divided in five phases, but we must note here that these phases were not as strictly defined as they may seem below. Actually the phases melted into one another – specifically the interviewing phases – which inevitably resulted in overlaps. The first phase – the literature study and document analysis (twelve months) – consisted of an exploration of the compliance domain and was carried out by means of studying literature and documentation on the domain of financial institutions and money laundering.

In a second phase, we carried out a number of exploratory interviews with a limited number of gatekeepers of the compliance field: compliance officers of the large banks in Belgium, the financial institutions’ umbrella organisation and AML consultants. Based on this information, combined with the information from the first phase, a web survey (standardised questionnaire) was developed. As contact addresses of compliance officers were either not available or, if available, protected for reasons of privacy, we were not able to send the survey directly to the compliance officers. However, the umbrella organisation for the financial sector, Febelfin, was willing to help us by sending the survey to all of their compliance contacts within the Belgian banks.2 A reminder was sent twice (Dillman, 1991). This resulted in the spring of 2007 in seventy-four filled-out questionnaires, which were analysed by use of SPSS (a statistical software package). The web survey allowed us to reach a larger amount of respondents at the same time, mapping their views and characteristics (Dillman and Bowker, 2001), and gave us the necessary basic information on which we could found the following phases. Despite the shortcomings such as low response rates, coverage errors and technical problems related to web surveys (Dillman and Bowker, 2001), we are of the opinion that the use of a web survey had several advantages. It allowed us to reach a relatively large number of compliance experts in a short period of time. The goal of this web survey was to get a first impression of the backgrounds of compliance officers, their opinions and views on AML regulation, cooperation and information exchange, but also to map different compliance practices.

The subsequent in-depth interviews (phase 3) built on the results of the survey and could give more context to the results. Again, being compliance officer is a delicate profession and this became clear when we started looking for contact information: names or addresses are not publicly available. Compliance officers were contacted through telephone calls to general information telephone numbers, and via general e-mail addresses. In combination herewith, we also made use of the snowball method: at the time of an interview, we asked respondents who they would recommend for an interview. In this phase maximum diversity was strived for, which implies that we contacted both large, medium- and smaller-sized banks, with the view of gaining insight into a broad array of compliance functions. In this phase, we interviewed twenty-three compliance officers (eleven large banks, seven medium-sized banks and five small banks). The interviews lasted on average 1.5 to 2 hours.3 Additional observations of three AML courses for bank employe...