eBook - ePub

renovatio urbis

Architecture, Urbanism and Ceremony in the Rome of Julius II

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Examining the urban and architectural developments in Rome during the Pontificate of Julius II (1503–13) this book focuses on the political, religious and artistic motives behind the changes. Each chapter focuses on a particular project, from the Palazzo dei Tribunali to the Stanza della Segnatura, and examines their topographical and symbolic contexts in relationship to the broader vision of Julian Rome.

This original work explores not just historical sources relating to buildings but also humanist/antiquarian texts, papal sermons/eulogies, inscriptions, frescoes and contemporary maps. An important contribution to current scholarship of early sixteenth century Rome, its urban design and architecture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access renovatio urbis by Nicholas Temple in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Signposting Peter and Paul

The Tiber's sacred banks

Today we have the festival of the apostles’ triumph coming round again, a day made famous by the blood of Paul and Peter. The same day, but recurring after a full year, saw each of them win the laurel by a splendid death. The marshland of Tiber, washed by the nearby river, knows that its turf was hallowed by two victories, for it was witness both of cross and sword, by which a rain of blood twice flowed over the same grass and soaked it . . . Tiber separates the bones of the two and both its banks are consecrated as it flows between the hallowed tombs.1

Written by the late fourth-century Spanish poet, Aurelius Clemens Prudentius, this description of the topography of the Tiber River in Rome, in the context of the places of the martyrdom and burial of St Peter and St Paul, is testimony to the long-held belief in the redemptive significance of the left and right banks of the river. Throughout much of Early Christianity and the Middle Ages, the partnership between the Princes of the Church, as the most venerated saints of Rome, was matched by the apparent symmetry of their consecrated territories on either side of the Tiber River. This topographical relationship was, however, more a symbolic reading than an actual reality. Indeed, Prudentius's account had little connection with the physical layout of the city of Rome, given that the hallowed sites of Peter and Paul were located at the periphery of the inhabited city. The description reaffirms that Rome's status as a Christian city, in the fourth century, was quite distinct from the nature of the urban fabric déntro le mura (inside the walls).

Under Constantine, the first Christian emperor, the programme of church building had been, as Richard Krautheimer explains, “confined to sites mostly on imperial estates and always on the edge of the city or outside the walls”.2 Constantine instigated an ambitious programme of church building on communal burial sites previously dedicated to martyrs and saints (St Peter's, St Agnese fuori-le-mura, San Lorenzo fuori-le-mura, San Paolo fuori-le-mura etc.). These essentially communal halls were built to accommodate growing numbers of congregation and no doubt to underline the imperial status of the religion.

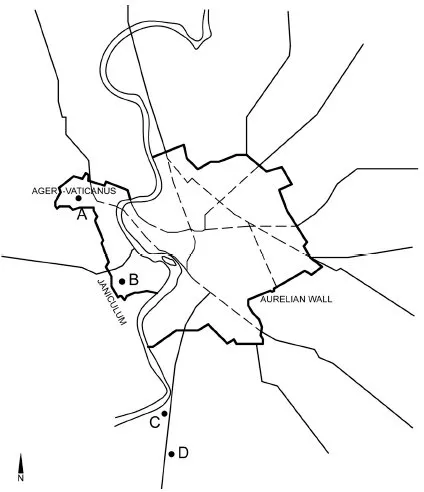

Figure 1.1 Outline map of Rome, indicating the Aurelian Wall and the construed locations of martyrdom and burial of St Peter and St Paul respectively. Vatican Hill/St Peter's Basilica (A), Janiculum Hill (B), Aquae Salviae (Tre Fontane) (C) and San Paolo fuori-le-mura (D). (Drawn by Peter Baldwin.)

While this situation of extra-territorial complexes changed from the late part of the fourth century, with the establishment of monumental basilicas within the city walls (such as Santa Maria Maggiore), Prudentius's model of sacred topography extra muros was nevertheless to persist as a ‘summary’ of Christian Rome throughout the Middle Ages. It largely defined the perception and representation of Rome conveyed in pilgrimage guidebooks to the city and the legacy of the main pilgrimage road through Rome.3 Entering the city from the north, via Monte Mario, the Via del Pellegrino (Via Peregrinorum) passed through the Borgo to St Peter's Basilica. Partly retracing the construed route of the ancient Via Triumphalis, it then crossed the Tiber River at the Ponte Sant'Angelo and extended south through the Ponte, Parione and Regola rioni (districts) of the city towards San Paolo fuori-le-mura.4

An important aspect of Prudentius's model of Rome's sacred topography is the way in which the sacrificial blood of martyrdom is expressed through its passage across terrain (turf) and flowing water (Tiber River). One implication of this relationship between human blood and topography is that Church liturgy becomes intimately intertwined with land and its hidden geological features, to the extent that the symbolic efficacy of the former is dependent upon the reception and appropriation of the latter for ritual purposes:

The quarter on the right bank took Peter into its charge and keeps him in a golden dwelling [basilica], where there is the grey of olive-trees and the sound of a stream; for water rising from the brow of a rock [mons Vaticanus] has revealed a perennial spring which makes them fruitful in the holy oil. Now it runs over costly marbles, gliding smoothly down the slope till it billows in a green basin [catharus]. There is an inner part of the memorial where the stream falls with a loud sound and rolls along a deep, cool pool [baptistery]. Painted in diverse hues colours the glassy waves from above, so that mosses seem to glisten and the gold is tinged with green, while the water turns dark blue where it takes on the semblance of the overhanging purple, and one would think the ceiling was dancing on the waves. There the shepherd himself nurtures his sheep with the ice-cold water of the pool, for he sees them thirsting for the rivers of Christ.5

In this description, we are presented with an account of the site of St Peter's Basilica, and its Early Christian baptistery, which assumes that the Vatican was somehow ‘fated’ to host the Apostle's martyrdom and burial. The implication here of the predestination of Rome's topography – as the consecrated ground of martyrdom – later serves as a powerful and enduring symbolism in medieval Rome. It constituted one of the key modes of communicating the redemptive layers of urban terrain, which were later to be appropriated by antiquarian and archaeological interests during the Renaissance.

Peripheral centres

The persistence of Prudentius's model of the sacred topography of the Tiber River must be seen in the context of the political and religious backgrounds of Constantine's building programme in Rome, and their later adaptations during the Middle Ages. The topographical arrangement of Constantine's Christian complexes, extra muros, was largely pre-empted by the construction at the Lateran of arguably the first Christian basilica.

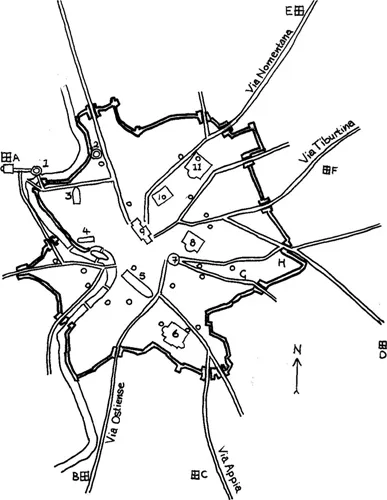

Figure 1.2 Outline map of Early Christian Rome indicating the principal roads, shrines and basilicas. Covered cemeteries and basilicas of martyrs: St Peter's (A), San Paolo fuori-le-mura (B), S. Sebastiano (C), SS. Marcellino e Pietro (D), S. Agnese (E) and S. Lorenzo (F). Churches: St John the Lateran (G), S. Croce (H). Ancient monuments: Hadrian's Mausoleum (1), Mausoleum of Augustus (2), Stadium of Domitian (Piazza Navona) (3), Circus Flaminius (4), Circus Maximus (5), Baths of Caracalla (6), Colosseum (7), Baths of Trajan (8), Palatine Palace (9), Baths of Constantine (10) and Baths of Diocletian (11). ‘O’ indicates locations of Tituli within the walled city. (After Krautheimer and redrawn by Peter Baldwin.)

Located in the eastern part of Rome on the Caelian Hill, close to the Aurelian Wall, the Lateran became the headquarters of the bishop of Rome, following Constantine's departure from the city to establish a new imperial capital on the Bosphorus. Formerly the location of the imperial barracks of Maxentius's home guard, Constantine is said to have donated the site to the fourth-century bishop of Rome, St Silvester. With the construction of a substantial palace during the early Middle Ages, the Lateran emerged as the political powerbase of the papacy.6 Unlike the other basilicas that Constantine commissioned on the outskirts of Rome, the Lateran was not the site of a martyr's grave or a venerated cult centre. Rather, it served as “an audience hall of Christ the King”, thereby promoting a direct allegiance between the Saviour and the Emperor.7 At the same time, the Lateran provided the principal initiation centre for the Roman Church following the construction of a large baptistery, on the site of a former domestic bath building on the west side of the basilica.

It is against this Late Antique background of the Lateran, as Constantine's Christian foothold in pagan Rome, that the complex of buildings acquired such political and symbolic importance for the popes. Its location, at the eastern periphery of the city, posed however a number of problems for the papacy, not least its isolation from the inhabited part of Rome. Up until the twelfth century the population of the city declined significantly, leading to large areas of Rome becoming effectively deserted (disabitato). One of these areas was the Caelian Hill, once a prestigious residential district of ancient Rome.

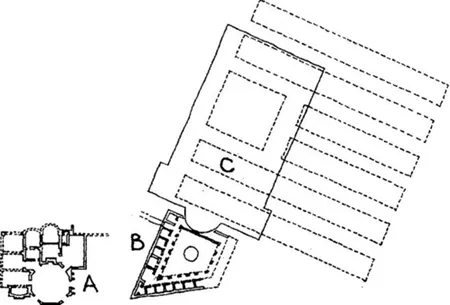

Figure 1.3 Schematic layout of the Lateran Complex (fourth century), highlighting the Constantinian baptistery (A) (formerly the Lateran bath building), Lateran House (B) and basilica (C) over the former barracks of Maxentius's home guard. (After Pellicioni and drawn by author.)

By the fourteenth century, following a period of sustained population growth, the inhabited parts of the city (abitato) were mainly concentrated in the quarters of the old Campus Martius, to the west of the ancient Corso. The most densely populated area was on the east bank of the Tiber River, in the Ponte, Parione and Regola rioni, an area that was to become crucially important for the papacy during the Renaissance, as I will explain in Chapter 2.

Given this concentration of the population in a relatively confined area of the city, medieval Rome could be described as a city within a city, between the abitato and the outlying patchwork of Christian communities dispersed in a landscape of spoliated ancient ruins. At the same time, there was another city, albeit more symbolic than actual, that constituted the extra-territorial constellation of venerated Christian shrines that surrounded the ancient walled city. This fragmented arrangement underlines the fact that medieval Rome lacked the kind of cohesion and hierarchy of spaces that characterised other medieval cities in Italy, such as Florence and Siena. This was largely due to the exceptional nature of Rome's history, which precipitated its rapid depopulation and the abandonment of large areas of the city, following the relocation of the imperial capital to the east.

In spite, however, of these dramatic changes in the fabric and urban structure of Rome, the rioni of the medieval city constituted a loose amalgam of urban communities, sustained largely by the ceremonial routes linking religious complexes. By the early Renaissance, as we shall see later in Chapters 2 and 4, this arrangement was formalised into what Charles Burroughs aptly describes as “a spatio-temporal system of liturgically linked holy places and memorials”.8 Through these ritual passages, religious festivals and ceremonials provided the most tangible means of engendering a sense of connectedness between otherwise isolated religious centres. This was most apparent during the ‘Holy Year’ (Jubilee celebrations), first introduced by Pope Boniface VIII in 1300. It was during these celebrations that thousands of pilgrims converged on the city to attend the graves of the apostles and martyrs. The Jubilee enabled, as Eamonn Duffy states, pilgrims “to gain indulgences, adding enormously to the prestige of the papacy and the spiritual centrality of Rome”.9

Given the significance of the network of pilgrimage routes in Rome, as the ‘glue’ that binds the dispersed and fragmented topography of the city, it is evident why Prudentius's account of the Tiber River carried such potency; it effectively defined the ‘backbone’ of Rome's sacred landscape, against a background of rapid urban decay, desertion and ruination. Attempts to restore parts of the city, and to give greater order to its topography through such initiatives as paving and widening streets, were substantially hindered by ongoing political and territorial feuds between the ruling baronial families and the papacy; claims of the Frangipane, Annibaldi, Orsini and Colonna families to parts of the city (that served as their strongholds) often resulted in internal conflicts and confrontations with the ‘lawful’ prerogatives of the pope. Supposedly conferred on the bishop of Rome by Constantine himself, as stated in a document known as the ‘Donation of Constantine’ (famously discovered to have been a forgery in the fifteenth century), these prerogatives gave the pope temporal authority over Rome and her territories.10

In spite, however, of the apocryphal nature of these claims to temporal authority, the Christian ‘Pontifex Maximus’ was presented by court hagiographers as the rightful inheritor of imperial rule in the West, which gave legitimacy to political initiatives and even military action.11 This aspect of the papacy was to become especially pronounced during the Renaissance, when aspirations to expand the Holy See in the Italian peni...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- renovatio urbis

- The Classical Tradition in Architecture

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- Figure credits

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Signposting Peter and Paul

- 2 Via Giulia and papal corporatism: the politics of order

- 3 Palazzo dei Tribunali and the meaning of justice

- 4 Cortile del Belvedere, Via della Lungara and vita contemplativa

- 5 St Peter’s Basilica: orientation and succession

- 6 The Stanza della Segnatura: a testimony to a Golden Age

- Conclusion: pons/facio: popes and bridges

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index