![]()

Chapter One

Living History Fiction

A Past to Excite the Senses1

Sue Gough, Wyrd

In researching historical fiction for children and young adult readers, I have come across a range of texts that rely on a living or lived experience of history to frame the historical story. These novels are similar to the time-slip narrative; however, not all examples use the traditional convention of time-slippage. I want to bundle these novels together—‘time-slip’ novels included—as examples of ‘living history’ narratives because they appear from the outset as a distinct literary form requiring particular reading strategies. The strategies I am identifying here are clearly comparable with the visual interpretative strategies required at living history museums. Living history sites use historical artifacts, reconstructions, and actors to provide the museum tourist with a sense of the past as tangible and living. Raphael Samuel (1994) convincingly argues in Theatres of Memory that ‘[i]f there is a unifying thread to these exercises in historical reconstruction it is the quest for immediacy, the search for a past which is palpably and visibly present’ (175). Living history museums offer live historical performances as a means of making the past more accessible to the visitor; re-enactment is underpinned by the principle that living history is more real than its static showcase complement. Nonetheless, this argument, although holding merit as a means of distinguishing museums and as a reason for interest in the field, is less useful on its own to the analysis of literary forms.

As will be shown in the following chapters, all historical fiction brings an inert past to life and requires from the reader some reflection on the present and history’s relationship to that present. What makes the Living history novel unique is the novelist’s desire to signpost the ‘pastness’ of history. As Jonathan Culler (1988) has noted in Framing the Sign, for a historical site ‘to be truly satisfying [for the tourist] the site needs to be certified, marked as authentic’ (164). The marking out of a historical site facilitates the demarcation, spatially or perceivably, of the past from the present. Discriminating the border of history requires an explicit sealing of the past, and so Living history fiction requires readers to successively (and perpetually) identify, assimilate and repel the past as they move in a linear fashion toward a more insightful understanding of the present world. Living history fiction clearly demonstrates how historical narratives for children use the past as an interpretive frame for the present.

The interpretive frame and how it positions readers to respond to historical narratives depends, in part, on readers believing the historical authenticity of the tale. Many authors of this type of text use peri-textual information such as an ‘Author’s’ or ‘Historical Note’ to confirm historical legitimacy. What most authors tend to write is that the past as presently conveyed is an accurate historical record and that the truths identified are consistent over time and therefore instructive for young readers. In the peri-textual material from King of Shadows (2000), Susan Cooper makes a direct address to readers in order to authorize the historical validity of her novel. She writes,

Cooper’s claim to historical authenticity is supported by her ‘thanks to Professor Gurr for his kindness in reading the manuscript of King of Shadows’. This is a clever way of endorsing the historic authenticity of the novel. Nadia Wheatley in The House That Was Eureka (2001) also uses the peri-textual material to make that customary claim to fact and fiction. The Historical Note begins with the stand-alone sentence: ‘Though this is a novel, the history in this book is real’ (406). The statement is followed by a non-fiction retelling of life for the working classes during the Depression. It reads not like a novel, with dialogue expressing the hopelessness of poverty, but more like a school history textbook, with facts and figures (to evoke for the reader that same sense of hopelessness and poverty). The authorial claim to historical reality has been supported throughout the story with excerpts taken from the time of the Depression evictions; for example, Wheatley tells readers that ‘reports of the Redfern, Leichhardt and Bankstown fights are taken from the newspapers of the time’ (409). These excerpts are differentiated from the fictionalized story by employing distinct font and page layout. As for the fictionalized historical tale, Wheatley writes that it has been based ‘on a great deal of primary research, as well as investigation of the battle site’ (409).

Cooper and Wheatley’s address to readers problematizes the distinction James Goodman makes between historian and historical novelist. Goodman argues, ‘Fiction writers do not represent experience so much as they create it, and their faith and allegiance is to the experience they create’ (247). Although none of the novelists discussed in this chapter would disagree with Goodman’s argument, most would be of the same opinion as Cooper and Wheatley, that the created experience is one based in and on historical textual traces and cannot therefore be solely understood as a created experience. Fictional characters generated from factual records embody both creation and representation. They signify reality by engaging in verifiable historical situations. The historical experience for readers is both invention and retelling. The Living history novel extends this axiomatic premise. The novel is indeed a product of the author’s imagination embedded within an historical context, but the past is not simply retold from surviving documentation—it has been witnessed by the modern eye. The Living history novel is seductive. It lures readers to align uncritically with modern perception. By persuasively inviting readers to assume a particular point of view the authenticity of the modern characters’ perception of the past is privileged.

The distinct reading subject position offered by Living history fiction relies on this alignment of readers with modern characters. Readers are positioned to perceive both the strengths and weaknesses of past and present times, ultimately reconciling the two in a present that faces chronologically forward. The existence of modern focalizing characters in Living history fiction places modern perception in a superior relationship to the past, despite recognition of a certain degree of malaise with the modern condition. However, before examining in more detail how Living history fiction positions readers to interpret the past, I will provide some clarification of the parameters of the sub-genre.

Defining the Parameters of the Living History Fiction Sub-Genre

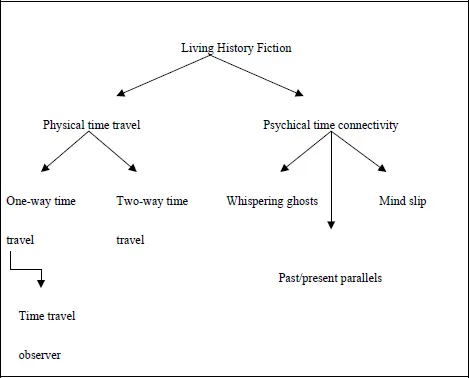

As noted in the introduction to this chapter, Living history fiction creates a coming together of past and present, either in a physical or psychical sense. The sub-genre can be further subdivided as shown in Figure 1.1 below.

In what follows I will flesh out the categories noted in Figure 1.1 with reference to the focus novels of the chapter.

The largest collection of Living history fiction is the ‘Physical time travel’ and, as indicated in Figure 1.1, time travel can occur in a number of ways. Of the various sub-categories, the ‘One-way time travel’ is the style most readily adopted. In this type of novel characters living in the modern world are transported to the past and, at story’s end, return to the present. Susan Cooper’s King of Shadows is a well-known example. The modern focalizing character, Nat Field, while preparing to play Puck at the newly rebuilt Globe Theatre, smells and hears the echo of past times and wakes up one morning in sixteenth-century London, still an actor, and still in the role of Puck but training to appear in a production alongside William Shakespeare. In the sixteenth century, Nat endeavors to understand the unfamiliar context into which he has been cast and, more importantly, he reflects on his life experiences in the twentieth century and uses the insights gained to let go of past sorrow and move his life forward.

Figure 1.1 Categorizing the sub-genre of Living history fiction.

Goldie Alexander’s Mavis Road Medley (1991) and Jackie French’s Somewhere Around the Corner (1994) are also typical examples of One-way time travel novels. Alexander in Mavis Road Medley uses the same place, different time approach to historical transition. In this book the 1980s teenagers Didi and Jamie are propelled through an erroneously generated time warp that deposits them in the 1930s Depression. Similarly French, in Somewhere Around the Corner, relocates a young homeless girl, Barbara, from a modern eviction rally in Sydney to a 1932 Depression eviction protest at the same location. The time shift facilitates Barbara’s rescue from the streets by Young Jim, who takes her back to his family’s squat in Poverty Gully. French provides a good deal of commentary on the generosity of people from the Depression years, despite their poverty, and the absence of such care in the modern world. I will return to this rumination upon the shortcomings of the modern condition further into the chapter as it is a thematic concern linked to the humanistic metanarrative of positive progression and a common theme for a number of time travel fictions.

The ‘Time travel observer’ is a small sub-category of the Physical time travel novel in which modern characters observe the past firsthand either through a porthole or as an invisible presence in the past. It is an especially pertinent category for my discussion of Living history fiction because it so obviously positions the experience of the past as an ameliorating one for the present character. In both Kit Pearson’s A Handful of Time (1987) and Jackie French’s Daughter of the Regiment (1998) the modern character is neither heard nor seen by historical characters and therefore effects no change in that historical location. Nonetheless, the past becomes an instructive tool facilitating a humanistic discourse on ageless human concerns and frailties. Positive character development by story’s end represents how individuals can grow in strength and wisdom by attending to the past.

‘Two-way time travel’ novels also draw readily upon the humanistic metanarrative of positive progression. In this sub-category of Living history fiction, modern characters often travel back and forth across time periods, and historical characters might also enter the present. Ruth Park’s Playing Beatie Bow (1982) was at the forefront of the resurgence of interest in historical fiction for young readers. The modern character, Abigail Kirk, is drawn to a mysterious young girl with shorn off hair. Curiosity entices Abigail to chase after the girl and as she weaves around the streets of Sydney’s The Rock’s district, Abigail is transported in time, arriving in the same place a century earlier. Penelope Farmer’s Charlotte Sometimes (1969), Hilary Bell’s Mirror Mirror (1996) and Catherine Dexter’s Mazemaker (1989) engage in a past present dialectic that ultimately presupposes the superiority of the modern age. Farmer’s Charlotte Sometimes is one of the earliest examples of the Living history novel to be discussed in this study. The characters Charlotte and Clare physically time swap, with Charlotte taking the place of the 1918 character Clare and vice versa. Farmer very obviously develops a predilection for modernity by narrating the entire story from Charlotte’s point of view. Readers become familiar with Clare’s time period but through modern eyes, and they only learn about Clare from a few diary entries and from descriptions provided for Charlotte’s benefit by Emily, Clare’s sister. This is also the case in Bell’s Mirror Mirror. The story is focalized by the modern character, Jo, and the past is consistently presented as ‘other’: The discourse positions the past in relationship to the present rather than the reverse. In Mazemaker, while Dexter uses fluid time travel and multiple time travelers, she also prefers the modern age by narrating the story from modern Winnie’s point of view. Again, the past is clearly signposted and, as with all novels raised for discussion here, the past is firmly sealed off and othered by the conclusion of the story.

Not as large a category as the Physical time travel, but still substantial, is the ‘Psychical time connectivity’. This category of text brings history alive through cognitive connections between past and present. The ‘Whispering ghosts’ sub-category includes novels in which spirits or specters communicate with modern characters, having some tangible effect on the present. Victor Kelleher’s Baily’s Bones (1988), Nadia Wheatley’s The House That Was Eureka (2001) and Felicity Pulman’s Ghost Boy (2004) are graphic examples of the category. In these three novels modern characters are compelled to consider who they are, how the past relates to their present and how to move forward in their modern context. In The House That Was Eureka, for example, Wheatley merges the past with the present by means of dreams and enduring familial connections. She also shifts between the present time and the past to give form to the dreams and to make sense of the connections between time periods.

Psychical time connectivity can also be framed within a ‘Mind slip’. In this type of novel the modern character slips into the thoughts and perceptions of a past character. Frequently, the slip is seen to benefit both the present and the past. For example, in Jackie French’s Macbeth and Son (2006) and Celia Rees’ Sorceress (2002), the mind slip makes possible the bringing to light or clarification of a story either lost or covered by subterfuge. The mind slip also represents a growth of awareness for modern characters as they start to form intersubjective relationships with others by the conclusion of the narrative.

The final sub-category of Living history fiction under the Psychical time connectivity branch is the ‘Past/present parallel’. Although it is possible to argue that such examples do not clearly fit into the Living history fiction sub-genre of historical fiction because there is no crossover of characters physically or cognitively, the multi-stranded narrative time facilitates overt correlations between historical periods, thus creating a psychical connection in readers’ minds between past and present. Furthermore, these types of novels—such as Sue Gough’s Wyrd (1993) and David Metzenthen’s Boys of Blood and Bone (2003)—function in the same discoursal manner as the more traditional time travel historical adventure.

Reading Living History Fiction as a Sensory Experience

As noted in the opening of this chapter, Living history fiction explicitly signposts the pastness of history by aligning readers with a modern point of view. This reading strategy is clearly comparable with the visual interpretative strategies required in living history museums that call attention to a sensory experience of the past. Living history sites use historical artifacts, reconstructions and actors to provide the museum tourist with a sense of the past as tangible and living. In an article on living history and historic houses, Andrew Robertshaw comments,

Robertshaw points out three key features of the living history museum experience: An authentic past is an unmediated past; acting out the past is performative; and sensory learning is more effective than reading a history book. There are clear parallels to be drawn here with the Living history novel, as both modes of presenting history have particularized formulas and hence limitations to reconstructing the past. Over the course of this chapter, I will make reference to this complexity of features identified by Robertshaw, beginning with the idea that a sensory approach to learning is more effective than the passive reading of documents and observation of artifacts.

The time-traveling Living history novels position readers to engage with the past as both intellectual inquiry and physical reality: Characters have seen, ther...