![]()

Part I

Artificial Intelligence

![]()

1 Early Artificial Intelligence Films

‘When are you Going to Let me out of this Box?’

Nowhere in cinema history has breathtaking visual spectacle and profound philosophical speculation been more successfully combined than in enigmatic director Stanley Kubrick’s SF masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey. Visually, the film broke new ground with its amazing stargate finale, while the attention to detail in the moon and spaceflight sequences was so accurate that NASA astronauts actually used the film as a training tool for some years following the film’s release, a feat even more impressive given that 2001 came out in 1968, the year before the first human moon landing (Stork, 1997, p. 2). On the speculative level, 2001 introduced HAL, the single most widely recognised representation of Artificial Intelligence in cinema or popular culture to this day. In doing so, the big questions about what constitute both intelligence and life itself—as they were raised in relation to the early writings on Artificial Intelligence and cybernetics—found their way into the broader popular imaginary via the silver screen.1 Indeed, the ‘intellectually provocative’ nature of 2001 was so dominant that many critics have argued that it finally put rest to the widely held ‘myth’ that SF cinema ‘cannot possibly be as thoughtful, as profound, or as intellectually stimulating as SF literature’ (Sobchack, 1997, p. 24). Speculation about the tenuous status of AIs is explicitly flagged early in the film during an interview with the crew of The Discovery in which HAL is introduced as a ‘computer which can reproduce, although some experts still prefer to use the word mimic, most of the activities of the human brain and with incalculably greater speed and reliability’ (emphasis added). The implicit question here as to whether HAL is actually alive or intelligent, and thus the counterpoint of exactly what being alive and intelligent mean in relation to human beings, develops as a major theme of 2001. It is that theme which will be explored below.

Ostensibly, HAL appears to fulfil Hans Moravec’s (1988, 1999) predictions of emergent disembodied informatic intelligences. Paul Edwards supports this contention through his reading of 2001 and other films featuring AIs which he divides into two categories: the disembodied and embodied. For Edwards, HAL is the ‘perfect representative of disembodied Artificial Intelligence’ (1996, p. 321). In the embodied category sit more recognisably humanoid AIs such as ‘robots, androids and cyborgs’, while HAL differs from these in that he appears without a defined physical form.2 The lack of obvious boundaries and HAL’s seemingly omnipresent gaze within The Discovery led Edwards to argue, borrowing from Michel Foucault,3 that disembodied AIs are all the more threatening because they overcome human limitations and ‘frequently present the invisible gaze of panoptic power’ (1996, p. 314). For Edwards and Moravec, HAL has literalised the mind/body dichotomy, and is pure mind; unrestricted by embodiment HAL is both more intelligent and more powerful. Even HAL’s murder of four of the five human crew is consistent with Moravec’s prediction that AIs—humanity’s ‘artificial progeny’ (1988, p. 68)—are the next rung on the evolutionary ladder, justifying (or at least explaining) any disregard for human beings, their redundant and outdated intellectual ancestors. Such a reading derived from Edwards and Moravec is premised on HAL being a disembodied entity. However, I wish to offer a different perspective: that HAL is indeed embodied, just embodied differently to human beings.

The first suggestion that HAL is more than just an informatic form or pattern comes during the interview with the crew of The Discovery in which the interviewer refers to HAL as the ‘brain and central nervous system of the ship.’ In organic terms, being the brain and central nervous system of anything would normally imply being that thing: however, the interviewer’s metaphoric embodiment of HAL appears to be tempered by the presumption that an AI is separable from the system of which it is part (in this case, The Discovery). HAL’s metaphoric function as the brain and central nervous system of the ship is reinforced by his abilities within that system: he can see all over the ship through his many glowing red eyes; he can control the onboard systems; he can communicate with the ship’s passengers; and he can even control the external pods. Moreover, the pods could actually be read as HAL’s limbs. A scene in which one of the pods is used to attack crew member Frank Poole begins with a combination of close-ups on HAL’s eye on the pod and on the arms of the pod extending threateningly towards Frank. It would be difficult not to read this scene as ascribing the pod’s agency as HAL’s. A strong sense of subjectivity is also evident in that on a number of occasions, scenes are shot from HAL’s perspective complete with a curving of the image evoking HAL’s own and unique point of view. HAL’s embodiment is also emphasised in that, unlike a standard computer, he cannot be simply programmed and switched on or off. Rather, HAL had a human instructor and, after being first activated, had never been turned off. When the human astronauts are contemplating disconnecting HAL, David Bowman points out that no 9000 computer such as HAL has ever been disconnected; he is concerned as to how HAL would react to the suggestion. In fact it is exactly HAL’s reaction to the threat of being ‘disconnected’ that heralds the AI’s dramatic turn against the astronauts.

The character development of HAL in 2001 is not restricted to HAL’s own actions and dialogue, but is also accomplished through contrast with the human characters in the film. As Vivian Sobchack (1990) has pointed out, Stanley Kubrick utilised a number of cinematic techniques in order to emphasise HAL’s human-like qualities and de-emphasise them in his human counterparts. Kubrick deliberately cast bland similar-looking actors in the astronaut roles whose banal actions and appearance render them almost sexless (Sobchack, 1990, p. 108). Also, their dialogue is dull and functional, designed to ‘emphasise the lacklustre and mechanical quality of human speech’ (Mader, 1996, p. 36). By comparison, HAL’s voice is far more energetic and emotional, ranging from intensely curious to completely paranoid. Moreover, the paucity of the forgettable dialogue serves to heighten the symbolic meaning in 2001 to the extent that some critics have argued that Kubrick created a ‘sheerly visual’ aesthetic form (Freedman, 1998, p. 304).

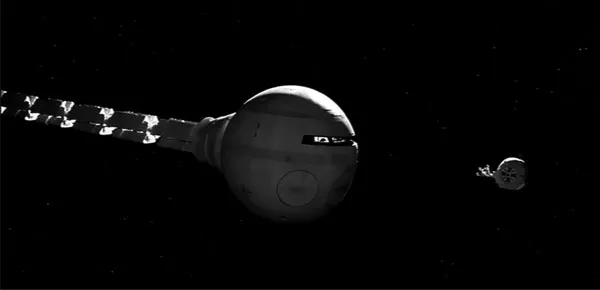

In semiotic terms, one of the more revealing scenes occurs when David Bowman attempts to re-enter The Discovery in his pod, but HAL will not allow Bowman entry, keeping the pod bay doors sealed shut. Visually, audiences are presented with two entities glaring at each other across the vacuum of space: The Discovery and the much smaller pod (which Bowman has severed from HAL’s control). Symbolically, this scene evokes the feel of two powerful animals, vying for dominance or control. Ironically, the confrontation would be at home in a nature documentary, with David Attenborough advising audiences in hushed tones that these two would soon battle for the ‘alpha male’ position. Moreover, it is during this scene that Bowman seems to realise that HAL considers The Discovery to be his body and will not allow interference with it, finally causing the astronaut to panic. As Vivian Sobchack notes, ‘HAL’s paranoia is the ship’s madness as well’ (1997, p. 71). David Bowman’s decisive response is to forcibly re-enter the ship and then dramatically lobotomise HAL. The use of colour in the lobotomy scene is also significant: in contrast to the generally sterile greys and whites of the rest of the ship, HAL’s symbolic brain chamber is a glowing (almost pulsating) organic red. Furthermore, colour is significant in terms of general characterisation in that Frank Poole and David Bowman wear dull grey flightsuits and have almost sickly white skin starkly juxtaposed with HAL’s glowing red and yellow eyes which stand out as vibrant, alive, and warm.

Figure 1.1 HAL/Discovery versus the pod in 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968).

Visually and symbolically, 2001 resonates with Donna Haraway’s provocative contention that ‘[o]ur machines are disturbingly lively, and we ourselves are frighteningly inert’ (1991, p. 152). The banality of the human crew juxtaposed with the emotional and energetic AI also resonates with a reading of HAL being ‘more human than human’ (the memorable slogan used in Blade Runner [Ridley Scott, 1982] to describe the arguably artificial Replicants). Moreover, the only indication that the majority of the human crew—the three astronauts brought on board The Discovery in hibernation—are even alive is through a computer display of their life signs (Sobchack, 1997, pp. 70–71). When the display shifts from a wave pattern indicating life to a flat line indicating death, the difference between being organic and being technological ironically appears to be rather small. Moreover, it is HAL’s final tragic scenes which are most powerful in evoking the ‘humanity’ of the Artificial Intelligence. After David Bowman forces his way back inside The Discovery and makes his way to HAL’s brain chamber, HAL switches from trying to rationally dissuade Bowman to issuing rather panicked pleas. As the astronaut uses his tiny scalpel to slowly lobotomise the AI, HAL seems to regress, losing his memory and then singing a child’s song as he finally slurs into oblivion. The choice of HAL’s final words being a child’s song reinforce both the idea of HAL’s innocence and humanity, as well as the idea that he had a lifespan and childhood rather than just being programmed into existence. Moreover, HAL’s demise is all the more dramatic as it conflicts with Moravec and Wiener’s notion of AI as a pattern of information, since at no point was Bowman threatening to actually erase HAL’s information, but only to disconnect it from the ship. HAL’s reaction is that of someone all too aware that their head is about to be severed. In N. Katherine Hayles’ (1992) terms, HAL recognises that his continued existence is dependent on the context of his ongoing material embodiment as part of The Discovery. Furthermore, in examining HAL as a metaphoric testing ground for human fantasies of disembodied informatic existence á la Moravec, HAL’s desire to remain embodied points to the ongoing unity of mind and body, not their separability. As Daniel Dervin has argued, it is not the threat of HAL becoming less like the astronauts, but rather that HAL was ‘a computer who has to be killed before he becomes any more dangerously human’ (1990, p. 101, emphasis added). In scrutinising HAL’s identity and authenticity, embodiment remains one of the key facets of subjectivity. Audiences discover that the spacecraft The Discovery was, in fact, HAL’s body.

The emphasis on HAL’s embodiment is just one of the strategies which emphasise bodies and embodied experience in the film. For example, in Annette Michelson’s important early critical work on 2001 she argues that the early scenes of weightlessness are disconcerting to viewers since ‘the basic coordinates of horizontality and verticality are suspended’ (1969, p. 60). As the camera follows the flight attendant in the interior of the first space shuttle, it is not so much that there is no reference point, but that these references are continually reset, as when attendant walks sideways up seeming walls, only to have the camera re-orient, suggesting a new stability, and then change once more. Similarly, while technically correct, the complete absence of diegetic sound in certain scenes set in the vacuum of space, including Frank Poole’s demise while outside The Discovery, are at odds with cinematic conventions (and the sonic impact of the seemingly incongruent juxtaposition of classical music with spacecraft and space stations are just as disconcerting4). Building on the phenomenological work of French theorist Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Michelson argues that Kubrick deliberately set out to disorient audiences then have them ‘snap to attention, in a new, immediate sense of our earth-bound state, in repossession of these coordinates, only to be suspended again, toward other occasions and forms of recognition’ (1969, p. 60). Emphasising HAL’s sense embodiment, often at odds with the banality of the astronauts, similarly orients audiences towards their own physicality. In discovering the importance of HAL’s body, audiences are simultaneously invited reconsider the importance of their own and ‘to rediscover the space and dimensions of the body as theatre of consciousness’ (Michelson, 1969, p. 63). That said, HAL is not the only means through which the relationship between humanity, technology, intelligence, and life is explored. Rather, a reading taking into account the enigmatic figure of the dark Monolith offers a broader perspective, especially with regard to humanity’s relationship with the nominally artificial.

Writing in a collected edition reflecting on 2001 entitled HAL’s Legacy, David Stork (1997, p. 5) argues that the film centres on different ideas of intelligence:

[I]n essence, [it is] a meditation on the evolution of intelligence, from the monolith-inspired development of tools, through HAL’s artificial intelligence, up to the ultimate (and deliberately mysterious) stage of the star child.

While HAL’s status as Artificial Intelligence is the focal non-human intelligence in the film, Stork reminds readers that HAL’s role in the film’s narrative is framed by the appearances of Monoliths which act as catalysts in the development of human intellect. Indeed, the chronologically expansive jump-cut in the film from ape-like primates discovering tool use (and violence) after the Monolith’s first intervention to the orbital station between Earth and the Moon just in time for the Monolith’s second revelation, circumvents recorded human history, moving from a fantastical past to a science fictional future.5 While the Monolith’s re-appearance presumably heralds another jump in intellectual development, the question remains as to whether it is the next stage of human intellect, or the first steps on a newly aware intelligence, perhaps, from an anthropocentric perspective, an Artificial Intelligence. HAL’s murder of The Discovery’s crew may be unsettling to the audience, but no more so than the slaughter which accompanies the first insights into tool use gleaned in prehistoric Africa: the similarities between these two acts are unlikely to be coincidental in the work of Stanley Kubrick, who was famously obsessed with the smallest details of his films.

The Monolith itself may not be ‘alive’ (at least biologically) but, rather, a sophisticated technological tool of an unknown alien culture. If the Monolith is a technological construct, then its influence over the primates in the distant past is actually a moment when the biological and artificial meet: human intelligence itself is a product not just of evolution, but of intervention by a technology which may very well be an Artificial Intelligence. Even if the Monolith is not intelligent per se, but is simply a complex tool, it is nevertheless the case that ‘natural’ human development is re-cast as technologically influenced from its earliest stages, challenging any unproblematic dichotomy between organic and artificial.

While 2001’s final scenes showing David Bowman passing through the Monolith’s stargate are among the most ambiguous in cinema history, they nevertheless offer further challenges to the distinction between human and artificial, and to the separability of mind and body. In his exploration of science fiction cinema in relation to embodiment and the sublime through the lens of Doug Trumbull’s special effects, especially those in 2001, Scott Bukatman argues that the ‘passage though the Stargate is a voyage “beyond the infinite,” a movement beyond anthropocentric experience and understanding’ (2003, p. 99). Amongst this flux of possibility, during Bowman’s ‘journey’ the visuals cut between the highly coloured alien landscape and extreme close-ups of the astronaut’s eye, reflecting the exterior colours. At one point, Bowman’s eye is reflecting reds and yellows which combine with his dark pupil to produce an organic eye image which is very similar to previous tight shots of HAL’s technological eye. While it would be presumptuous even to attempt to assign a singular meaning to this sequence, it is nevertheless clear that visually, the stargate special effects sequence aligns the organic astronaut and Artificial Intelligence in a manner incompatible with the liberal humanist dichotomy between human and machine.6 Moreover, this kinship is narrated not through discussion, but through the alignment of the optical centre of embodiment (a region also traditionally associated with the ‘soul...