![]()

1

You Can Be Like Us

American Intervention in Italian Reconstruction

THE AMERICAN MYTH IN ITALY: BIRTH, DEVELOPMENT AND DECLINE

By the late nineteenth century it was commonplace for Italians to perceive America as a land of prosperity, opportunity and freedom: an American myth had become part of Italian life. It played a large role in the decision of numerous Italians to emigrate to America. This vision of America ‘was kept alive through the letters of over four million immigrants who settled in America between 1880 and 1920’ (Liehm 1984:34)1.

An image was conveyed of a country where everything was allowed, a place in which people could express themselves in ways that they could not in Italy. Sergio Pacifici, in his Guide to Contemporary Italian Literature (1962:305), explains this image of America Italians had at the time:

Dominique Fernandez (1969) endorses Pacifici’s analysis and traces the boundaries of the American myth in Italy. He expresses the view that the early success of the Fascists in taking control of the Italian State had the effect of prompting many Italian intellectuals to take up American literature and culture as an antidote to dictatorship. Fascism had the effect of deepening the absorption of American literature by a large proportion of the Italian intelligentsia in a way that was more intense than the experience of their counterparts in other European countries.

According to Fernandez, the dates of this absorption of the American myth through culture and literature are the years between 1930 and 1950. It is in the thirties that many Italian intellectuals started reading, translating and becoming fascinated by American authors. Cesare Pavese’s essay “Un romanziere americano, Sinclair Lewis” (published in La Cultura in November 1930) signals the beginning of the myth, which ends with Pavese’s death (1950). Fernandez chooses to ascribe the birth of the myth to the years 1930 to 1935, the period during which many of Pavese’s articles were written; the original 1941–1942 publication of Elio Vittorini’s anthology Americana marked the myth’s climax; from 1947 the myth went into a decline that concluded with its demise as a cultural force in 1950. Guido Fink (1980:62) argues that it ended earlier, citing Pavese again, who in 1947 asked: ‘Is it us who are getting older, or it is that this little bit of freedom has been enough for us to distance ourselves from it?’. Luciana Castellina (1980:46) chooses to argue that the myth endured until the Vietnam War, when many Italians came to perceive what they regarded as a conflict between the interests of American imperialism and those of the Third World.

However, the myth started to be shaken just after the post-war presence of the American military in Italy. Fernandez argues that this is due to American culture having lost its allure. No longer forbidden, as it had been under the Fascist regime, the paradox of the myth was becoming increasingly apparent, i.e. that Leftist intellectuals would not have supported capitalist America in any other circumstances than under Fascism (Fernandez 1969:106). At the beginning of the Cold War, America came to be viewed in a new light; one that Luciana Castellina (1980:43) terms ‘an economicfinancial power, with imperialist aims’.

The Americanists shared a common ground with regard to the myth. They all referred to America as a young and vibrant land that was full of contrasts: novelty and tradition, wilderness and industry, educated and uneducated people.

The importance of the cinema in the development of the American myth in Italy has been widely acknowledged. In the 1980 collection of essays Il mito americano—Origine e crisi di un modello culturale, by cinema historians Gian Piero Brunetta and Guido Fink, the experience of American cinema in Italy is regarded as having done more to consolidate the American myth than any other medium. The authors analyse some of the most popular genres and the American ideology that they attempt to transmit. The power of American cinema lay, at least at the beginning, in its ability—as Brunetta (1980:21) states—‘to maintain the optimism that many Italians felt was needed at the time. Even the anomalies were seen as diseased excesses, contained within a fundamentally healthy body’. Guido Fink (1980:59) identifies the Italian intellectual crisis of confidence in the American myth as coinciding with the myth’s success in spreading to the broader Italian populace: while the intelligentsia were starting to wake up from the American dream, the general population were becoming increasingly fascinated by it, especially through the medium of cinema. Images of the Dream Land were becoming familiar to everyone through the use of dubbing English into Italian, making the stranger into a friendly figure.

Brunetta’s and Fink’s essays raised the issue of the ideological role of American cinema, but mainly in relation to the cinematic techniques used during the 1940s and 1950s. According to them such techniques as reverse angle sequences and long shot, extensively used from the 1940s, had an ideological meaning that could be analysed in contrast to those that were being used to make Italian movies.

The cultural, political and economic influence that the United States exerted on Italy and how this affected the development of Italian cinema was also acknowledged by historians in terms of the relationship between cinema and mass consumption. Analysing the role of American Government and of its cultural policy from the end of the Second World War, Sangiuliano (1983:34) expresses the view very clearly affirming how wherever American cinema goes, more American products are sold.

AMERICAN INTERVENTION IN ITALIAN RECONSTRUCTION, U.S.-STYLE CONSUMERISM AND NATIONAL IDENTITY

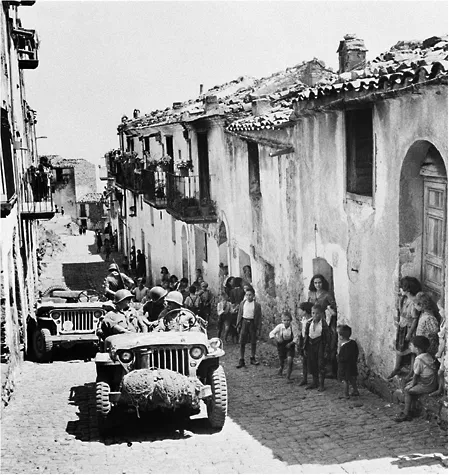

In September 1943, with the Allies landing in Salerno, the United States military commenced a direct martial-Governmental presence in Italy (Clark 1984:303). At the end of 1945, the Allied Military Government transferred to the Italian Government control of those Northern provinces (the last to be left under the AMG’s authority) while increasing the number of combat groups to six divisions of 9,000 men each2. These years had a profound effect on Italy and Italians.

The Allies were often regarded as a force for liberation from the Germans. However, the distinction between liberation and occupation can be a subjective matter3. In Rebuilding Europe, David Ellwood defines the role taken by the United States Government in relation to European economies and to European national identities. After the Second World War, with memories of Fascism still very much alive, many European States, in an attempt to promote peace, included a formal recognition in their constitutions that national sovereignty should be limited. In Italy, national identity had been undermined by the experience of prolonged Fascist rule. The country looked to America not only as a source of economic support, but also as an economic model to be followed. During the Fascist era it had been commonplace for people with low incomes to regard America as a dreamland of opportunity, but the same people could not ‘indulge any consumerist fantasies’ (Duggan 1995:12). After the war, and assisted by American economic intervention, Italians started to rebuild their economy and were able to see the prospect of consumerism on the horizon4. Ellwood stresses the importance of how economic reconstruction was at the heart of American foreign policy and how economic recovery was even more important than military aid. As Hamilton Fish Armstrong—editor of Foreign Affairs—Stated in 1947:

It was important for the American economy to develop in Europe the ‘mass production for mass consumption’ that was already the basis of the American market (DeLong 1997:2). However, large-scale low-cost production, which had worked in America, was taken up more slowly in Europe than had been anticipated. In June 1947 Americans launched the Economic Recovery Program—widely known as the Marshall Plan—which was not simply an economic manoeuvre but which also sought to establish financial stability as the foundation of ‘political independence’. The Program—strongly supported by the Vatican5—incorporated the desire to establish in Europe those American ideals that would promote democratic changes. The Plan was an expression of the American commitment to establish a strong presence within Western Europe. The reason for this was understood by many, especially in Italy, as a desire to stop Communism.6 The massive Vatican-backed Christian Democratic propaganda campaign prior to the April 1948 Italian general elections, achieved its purpose of securing an electoral victory for the forces of conservatism. The Christian Democrat won 305 out of 574 seats in the Camera dei Deputati, the lower parliamentary chamber, and 131 out of 237 in the Senate.7 The Communist Italian Party was denied a central position on the national stage.

In Ellwood’s view, the reason for America’s strong presence in Italy was also a way ‘to put forward a positive vision based on America’s own experience: “A higher standard of living for the entire nation; [ … ] greater production”, as a Marshall Plan propaganda booklet told Italians in 1949’ (Ellwood 1992:62). This point is of importance in accounting for the commonplace attitude amongst Italians towards ‘this positive vision’ and how the same vision shaped Italian identity. A better standard of living, together with a war against the totalitarianism that sought to threaten the American way of life, were the two objectives that were sought by American foreign policy in Europe. Ellwood feels prompted to write on the prospect of a possible Americanisation of Europe:

Productivity, prosperity and mass consumption were the fundamentals of the American economic model that the U.S. Government was seeking to export to Europe.

With the arrival of peace, from 1946 much of western and central Europe came to be characterised by a distinctive feature: Catholic political parties rose to dominance in Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg, Southern Germany, Italy, France, Austria and Hungary. In the case of Italy, the country faced a situation that was similar to that which had emerged after the First World War, when a single-party (then the Fascists, now the Christian Democrats) was at the head of the country. When ruling parties had to face the electorate, the process of Americanisation had the potential to be a political liability. When looking at Italy in this era, the difficult role of the Christian Democrats in their relationship with the Catholic electorate appears evident. While on one hand, the Church hierarchy was happy to support American opposition to Communism, on the other, it did not appreciate American consumerism, which was in part promoted through the imagery of Hollywood. While Duggan (1995:21) shows how the Catholic Church understood the new mass media and how it could deliver its own message, Ellwood sees a difficulty for the Christian Democratic Government. Welcoming the new mass media meant embracing certain aspects of American lifestyle, and allowing it to appeal to ordinary Italians. In his attempt to define Americanisation, Ellwood takes into account America’s daunting presence on the political, economic and social levels. He admits that the European countries affected by this process of Americanisation were not entirely free to refuse it because America was able to draw attention to the Communist threat as a justification for its promotion of consumerism (Ellwood 1992:236). In Italy, while the Christian Democratic Government seemed prepared to accept the process of Americanisation on a consumerist level, on a cultural level it had to find an alternative, if it was to maintain the support of the Catholic Church hierarchy. In 1952 Alcide De Gasperi, who served as the Prime Minister of Italy from July 1946 to July 1953, felt the need to State to a trade union audience that even if workers were becoming Americanised as consumers, they still maintained European characteristics, based on history and tradition (Zunino 1979:364). So, the Christian Democratic Government accepted the American economic model but still sought to rebuild Italian national identity in a framework that was determined by European history and culture.

The issue of the post-1945 Americanisation of Italy has developed a secondary literature. David Forgacs (1993:157–159) chooses to question the association of Americanisation and national identity, considering the importance of how Italy reinvented the American model, a topic of particular relevance in cinema. In his “L’americanizzazione del quotidiano. Televisione e consumismo nell’Italia degli anni Cinquanta”, Stephen Gundle (1986:561–594) uses television as an example for investigating how American culture was received and mediated by Italian society, concluding that the Catholic Church and the Christian Democrats were importa...