![]() Part I

Part I![]()

1

Introduction

Changes in Modern China and their Causes

Overview

Defining the Modern Era

The term ‘modern China’ as a historical concept has remained rather elusive. In Mainland China, 1840 is regarded as the starting date because of the First Opium War, a date to mark China’s defeat and decline. Given Jesuits once dominated the Ming and Qing Imperial Observatory and their modern calendar affected the everyday life of the ordinary Chinese,1 taking 1800 as part of China’s modern history is well justified.

But China’s modern era was not one of romance. China endured a great many serious crises frequently and on a colossal scale: society-wide opium abuse; empire-wide unrest; wars between warlords, republicans and communists; lasting political purges; and the unparalleled poverty. One wonders whether China was keener on building a nation or dismantling it.2

Old Narratives and New Debate

It has often been claimed according to the Marxist Eurocentric doctrine that before 1800 China had already been infected with a wide range of social ills. China’s alleged ‘feudal system’ comprehensively stifled the growth of progressive capitalism. China did not collapse thanks only to its geopolitical isolation.3 A liberal and non-Eurocentric view sees China as a case of missed opportunities, considering its track record of creativity and ingenuity.4 But both sides have agreed, however, that changes were needed and benefited China.

Against this backdrop, the literature on China’s modern history has been dominated by the three ‘Fs’ (feebleness, failures and falls of old regimes) and three corresponding ‘Rs’ (rebellions, revolutions and recovery under new regimes). The alleged determinants for China’s ‘Fs’ varies from internal Confucian conservativism to external imperialism and colonialism. The need for revolutions is believed to be consentaneous.5 There is even tacit teleology of revolution associated with modern China.6

With this ‘F-R’ paradigm, the entire history of modern China has often been portrayed with six neatly interlinking points:

- By 1800 the Chinese culture had become inward-looking, complacent, decadent and lethargic. Population pressure mounted; disasters were frequent; ‘feudal landlords’ were excessive rent-seeking, and people were universally poor. Meanwhile, the Manchu Qing government was corrupt and despotic. The civilisation began to fail.

- Qing weakness was ruthlessly exploited by predatory foreign powers. The opium trade and the Opium War were only the beginning. China paid the unprecedented war reparations and granted ever-increasing foreign privileges on China’s soil. China was semi-colonised.

- Inspired by Western patriotism, a group of republicans (often called ‘nationalists’) emerged and fought against both the Manchu conquest and foreign imperialism. China began to stir from her slumber.

- However, the republicans were neither radical enough nor powerful enough to solve all of China’s problems. They ended the Manchu rule but did little to fight foreign imperialism.

- New hope was stimulated by PRC as a workable model with which the Chinese population won their struggle against foreign imperialism. China modernised fast and became a nuclear power.

- After Mao Zedong (or Mao Runzi, 1893–1976), Deng Xiaoping’s reforms made the functional Maoist economy more efficient. China’s miraculous growth soon followed.

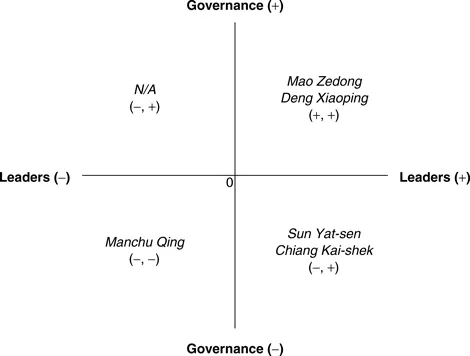

Embedded in this linear and nationalist narrative is the stylised, convergent progress of government and political leadership, demonstrated by moving anti-clockwise in the following Figure 1.1, from the Manchu Qing to Deng Xiaoping (positive = strong, negative = weak).

Figure 1.1 Conventional ratings of qualities of states and state-builders

Appealing to Chinese national sentiment as well as to the Western sense of guilt over their aggressive past, this narrative has formed the normative mainstream.7

The revisionists have now argued that until c.1800, China’s economy remained strong to match the West in manufacturing outputs.8 It remained a major exporter of consumer goods and a major importer of silver through the ‘Manila Galleon Trade’.9 The Qings also maintained a respectable living standard despite little modern input.10 Even the large quantities of opium imports suggest an affluent economy with high disposable income.11 Given China’s relatively egalitarian structure, growth benefited ordinary citizens.12 The California School even suggests that China’s indigenous institutions and economy could have continued indefinitely.13 All this casts serious doubt over the cliché of malfunction in Qing society.14

Revisionists have also indicated that the Qing state was anything but despotic.15 Unlike those who have used Mao’s despotism as a living model for pre-modern China, the new view indicates that the Chinese dictator was not an emperor in a Mao’s suit but another Stalin with a Chinese face.

The revisionist insight raises legitimate doubts about the teleological notion of changes in China. First, most changes were driven by ideologies that were imported from the outside. There is an issue of how relevant these ideologies really were to ordinary people’s needs, because their application in China often made losers. Second, decisions were routinely made by a tiny minority in society. These players had very different mindsets, agendas and approaches from each other as well as from the masses.16 Third, these changes often took place randomly with undue frequency. If this is the way to treat a patient, the illness was almost certainly exacerbated.

Common Myths

There are a wide range of common myths in circulation on both traditional and revisionist camps. The standard view has been that the Opium War woke up the Chinese general public who then supported nationalism. This nationalism facilitated industrialisation and modernisation. All are so neat. But such neatness is not automatically accurate. Until the 1920s, ending China’s ‘unequal treatises’ was not on the agenda of most political groups. Instead, China’s movers and shakers were overwhelmingly pro-foreigners and pro-foreign powers.

The next issue is that of revolutions. There has been so far no evidence the Taipings did anything remotely revolutionary. There is no evidence that Sun Yat-sen was responsible for the 1911 Wuhan Mutiny or the 1912 abolition of the monarchy. The fact that Mao spent more time and energy purging his fellow communists and communist sympathisers put a big question mark on whose side he was really on.

Finally, there is the question of speed, scale and scope of industrialisation and modernisation. Until 1977, China’s industrial schemes were never enough to upset China’s traditional economy. The real structural change began only after 1978.

Seeing the Role of the State in a New Light

The Chinese private economy was stable most of the time prior to 1949. Logically, if the economy went well, the source of problems could be the state.17 Scholars have sensed the role of the state in modern China, but many only touched on it lightly;18 others took a static view as if the state was frozen.19 The rest have had no reference to it at all.20

The Role of the State as Seen by Economists

In classical and neo-classical economics, human society is idealised as a collection of atomised individuals who act universally independently and rationally. Through a functional market, an optimum in resource allocation will be achieved for all. Any meddling with the market by the state only distorts the process and creates losers.21 The best state is thus a servo system that Adam Smith called ‘night watchmen’. A vast body of literature has pointed out that in reality the state was indeed responsible for asymmetrical information, price distortion, and economic rent, not to mention market failures.

The modern economics’ view on the state is also technical. It shuns the issue of ‘who serves whom’. So, the state is taken as one of the many variables, without power hierarchy and asymmetry, jointly contributing to the total output in a production function.

The Role of the State as Seen by Political Scientists

Political sciences see the state differently. The conventional wisdom on the raison d’être of the state is three-fold. First, it is an organisation which exercises the exclusive authority to maintain social order within a territory. Second, it has exclusive right to fence off foreign interference and takeover. Third, it also monopolises certain information to protect national interests or national security.

But there are always multiple ways to fulfil the basic duty of the state. A chosen way is often person...