1

Introduction

“Scenes of Peace and Quietude,” or Victorian Fantasies of Suburban Utopia

Imagine yourself walking down a street in the London metropolitan area, circa 1860. Mud sucks at your feet as you walk; the straw that has been put down to absorb moisture has long since outlasted its usefulness and merely gets in your way, releasing a faint whiff of mildew at every step. When the breeze picks up, you get pungent reminders that there is an open sewer or a multitude of bad drains, or both, somewhere nearby, and you begin to wonder just what, exactly, has made the streets so muddy. As you pick your way carefully down the street, trash whirls around your legs and ankles, and occasionally you see what you believe to be half a plate or a bit of teacup scudding across one of the many empty lots. Broken bricks, bottles and a variety of discarded building materials lie in abandoned heaps at street corners and in side yards, and although you cannot see them, you get the distinct impression that someone in the area is raising pigs.

Having reached your destination, a small semi-detached brick house with a paved garden, you follow the gravel path to the front door and knock. Upon entering you immediately sense, both by feel and by smell, the damp that pervades the house. While you wait to be announced, you nudge the hall carpet with your foot; immediately a bevy of black beetles and centipedes scurries for cover. You shiver as a draft of cold air blows across your neck, and you wonder how anyone could be expected to stay healthy living in a home, and a neighborhood, such as this.

Where are you? Seven Dials? Shoreditch? Some run-down lane in the East End? Might it surprise you to find that you have been visiting one of the newest suburban developments in Shepherd’s Bush, or Belsize Park, or Tooting Bec? It certainly surprised many of those middle-class families who moved to the suburbs in the second half of the nineteenth century, looking for peace, quiet, privacy and an alternative to the unhealthy atmosphere of the City. Instead of a green suburban idyll, what they found, in many cases, was a repetition of the evils of urban living they had been trying to escape: bad drains, little public sanitation, poorly constructed houses that were as damp as any lower-class hovel in the city, and less privacy than they had been led to expect. Certainly, there was no guarantee that the neighbors were as respectable as they might have wished. Of course, it is not unreasonable to find that space on the boundary between urban and rural would include many of the qualities of both. If we subtract the garbage and building debris, the preceding description of a typical suburban house could as easily be of a cottage in a sleepy agricultural village as an urban two-up two-down. However, the Victorian middle class expected more of their suburbs—and suburban space was very much considered “theirs.”

That the middle class came into its own in Britain in the nineteenth century is well documented, but despite its continued consolidation of power and cultural dominance throughout the century, the issue of class identification—who was in, who was out and how one was to know—remained a contested issue, primarily among those who considered themselves “in.” As membership in the middle class grew throughout the century, and as members of that class tried to find ways both to define themselves in contrast to other classes and to solidify their power base, the suburb and its attendant lifestyle came to represent everything that was vital to the middle class’s perception of itself. Cultural, social and literary critics have investigated the ways in which middle-class identity is constructed in Victorian texts for many decades, but very little has been written about the suburbs as a site of the struggle to define and codify class identification in the so-called High Victorian period. Supposedly, the suburb engendered domesticity, provided privacy and protection from the masses, promoted respectability and simulated the country-house lifestyle on a scale that was less grand, less wasteful and altogether more in line with middle-class values of prudence, propriety and comfort than actual country-house living. Presumably, only those who had achieved middle-class status, as defined by salary and occupation, could afford to live there, and, as there was nothing there but street upon street of houses, no one but those in the middle class would want to go there. This was the theory; the reality turned out to be quite different.

The notion that the nineteenth-century suburbs might have something interesting to tell us about the development of Victorian culture remained relatively uninvestigated until the last third of the twentieth century. In the 1970s, several geographers and sociologists, led by H. J. Dyos, became interested in the Victorian suburb as a historical artifact and studied exactly who moved into and out of the suburbs, what kinds of businesses were established, what rents were charged, how many families lived in each house, how long houses remained unlet and other minutiae of Victorian suburban life. What they found was surprising, to say the least. Rather than a vast band of quiet middle-class households, what these scholars found was a constantly shifting, economically unstable, socially heterogeneous space where once-respectable middle-class neighborhoods could become working-class refuges within ten years, and full-blown slums within forty.

Knowing what suburban realities were, where and, perhaps more importantly, what was the Victorian response to suburban living? We should expect to see this response emerge in a variety of mid-century texts, given that the Victorian middle class had invested heavily in suburbi1 (in every sense) based on an idealized notion of suburban living that was not always manifested in reality. In truth, we do not have to look very hard to find the response—writing about the suburbs abounds in a wide variety of texts, both fictional and not, throughout the Victorian period. The London suburb came into its own in the last third of the nineteenth century, and not coincidentally the number of literary works that take the suburb as their subject increases dramatically during this same period. This project is an attempt to resurrect at least part of the discourse of the suburb as a space of cultural contention by examining the literature produced around and about the subject. At the same time, this work aims to recontextualize Victorian fiction for modern readers within the framework of middle-class anxieties about suburban space and what it signified.

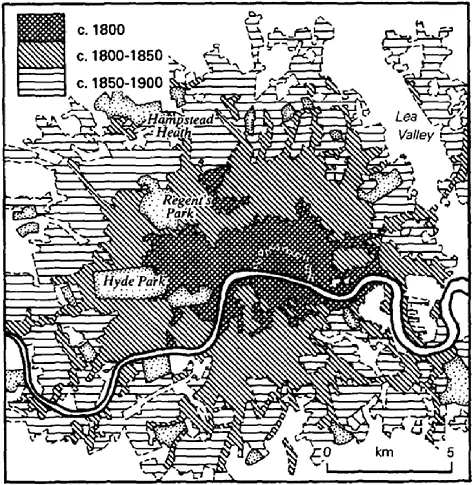

Although suburbs developed around every major city in England and most cities in Ireland, Scotland and Wales during the nineteenth century, my own study focuses primarily, although not exclusively, on portrayals of the London suburbs. Other urban centers certainly played an important role in the development of the Victorian city, but London has a special connection to the whole idea of the suburbs. There, the meaning of suburban space continued in flux much longer than it did around any other English urban center, such as Leeds or Manchester, where most development had stopped by 1850 (Burnett 56). In contrast to northern cities, the London suburbs grew fifty percent per decade between the years 1861 and 1891 (Dyos 19), and Figure 1.1 reflects this growth. According to Gareth Stedman Jones, “the greatest growth in the county of London … occurred in the decade 1871–81” (324), with building cycles peaking in 1868 and 1881 (Thompson, Introduction 13). In fact, the suburbs of London were the fastest-growing areas in all of England in the 1870s (Briggs, Victorian 324). This study focuses on literary constructions of the suburb that flourished from immediately before the first boom in the 1850s through about 1880, at the crest of the third boom cycle; it is my argument that during this period writing about the suburbs maintains a fairly consistent confidence that the space can be controlled and/or reclaimed by the middle class. After that period, as I explain in the final chapter, writing about the suburbs, and the people who live there, shifts its tone significantly.

The explosive nature of London’s growth is clearly visible when viewed via a succession of detailed street maps published throughout the period. An 1837 map, Environs of London, by Thomas Moule shows a pre-boom London that is clearly contained. A developed area north of the Thames, represented by dark grey blocks, is labeled LONDON in large letters; Regent’s Park sits neatly on its northwest border. Hyde Park marks the western boundary. On this map, developed London does not extend eastward past Limehouse. South of the Thames, a much smaller developed area is indicated as SOUTHWARK, almost as if it were a separate city. The surrounding area appears to be primarily open fields and green spaces—commons and large parks, such as Richmond, Wimbledon and Wembly,

to the south and west; marshes and forests, such as Hackney, West Ham and Epping Low, to the east. There is some evidence of the beginnings of ribbon development, indicated by small black squares along major routes; these are most evident westward through Hammersmith toward Brentford, southward through Clapham toward Balham and Tooting Bec, northward toward Stoke Newington and southeastward through Camberwell and down toward Lewisham. But this development does not appear to be making much of an impact on the open spaces beyond the main routes.

Cross’s London Guide of 1851 shows how London has crept outward in the intervening fifteen years since the publication of Moule’s map. As on Moule’s map, “developed” London is indicated by dark-grey boxes indicating blocks of buildings (rather than individual houses). Both Regent’s Park and Hyde Park are now about halfway surrounded by building; Brompton and Chelsea are clearly visible as well, whereas on Moule’s map there were only a few dots in this area south of Hyde Park near the river. Northward, Islington and Camden Town, which on Moule’s map were outside the developed area, are now part of it, although just on the northern edge. On the south side of the Thames, Cross’s map also indicates some significant growth south and west; eastward, there appears to be very little change—there is only slightly more grey space east of Limehouse Basin.

By the next decade, Stanford’s Library Map of 1862 indicates that Hyde Park has been completely enveloped, while Regent’s Park retains a bit of space to its north, mainly thanks to the Primrose Hill park and cricket grounds. The area between Chelsea and Millbank along the Thames has been completely filled in. Highbury is now on the northern edge of expansion, along with Stoke Newington. Eastward, development has edged toward Hackney Common and beyond Mile End. South of the Thames, the leading edge of expansion has come as far south as Streatham and Tooting Bec. Eastward, south of the Thames, there is a line of almost continuous building from Walworth, through Peckham to Greenwich. By the end of the century, as indicated in Stanford’s Map of Central London, 1897, the grey areas extend in an almost continuous mass westward to Shepherd’s Bush and Hammersmith. The area northwest of Hyde Park—Notting Hill and Kilburn—has been completely filled in. Eastward, the areas around London Fields, Hackney and Bethnal Green are also almost entirely grey. Tellingly, the 1897 Stanford map has shifted its center point westward—this Map of Central London puts the junction between Green Park and Hyde Park in the center, while most earlier maps had the junction between the City and Westminster (around where the Strand meets Fleet Street) as their center point. This shift in focus cuts out a good deal of south (Balham, Tooting), north (Stoke Newington) and east (Greenwich) London areas. These changes, both in the physical construction of London and in mapping it, reflect the ways in which the whole idea of what constitutes “London” was in flux throughout the second half of the nineteenth century.

The unprecedented and uncontrolled growth of London meant that, during the period I investigate, the “limits” of what was urban and what was ex-urban were constantly shifting around London, more than any other city in Great Britain, which engendered real concern about the scope of the change that was being inflicted on London and the surrounding countryside, including whether it would ever stop, or could ever be stopped. This does not exclude other cities from consideration in this work, of course, and I also discuss stories set in the suburbs of Edinburgh, Manchester and Dublin. However, it is worth noting that the authors of those particular works, including Sheridan Le Fanu and Harriet Martineau, either lived permanently or spent significant amounts of time in London during their careers, and so it could be argued that the zeitgeist of that city’s growth influenced their perceptions of suburban growth in other, less volatile, cities.

But how are we to define what constitutes a “suburb,” precisely? As Gail Cunningham has pointed out, the definition may lie largely in perception or attitude, rather than in specific locations (e.g., Islington or Camberwell) or a specific distance from the city center (424). This difficulty is largely the result of the expansion of the city’s boundaries over time; for example, there was a time when Westminster was a village set apart from London proper, but very few Victorians would have seriously considered Westminster a suburb by 1850—it had been fully incorporated into London’s urban space. On the other hand, early in the nineteenth century areas like Herne Hill or Hampstead were considered villages rather than suburbs, but by 1880 their classification had clearly shifted—they are not, like Westminster, part of the City of London, but they are definitely suburbs of it rather than neighboring rural enclaves. Even within the thirty-year period under consideration here, an area like Islington (a village itself in the early part of the century) would have experienced enough growth, especially to its north and east, to make it a question as to whether it was still suburban rather than fully urban.

The Victorians themselves defined what constituted a “suburb” quite broadly. Some sources, such as London City Suburbs as They Are Today (1893), actually do include Westminster, defining “suburb” as anything outside the City proper. Others, such as James Thorpe’s Handbook to the Environs of London (1873) ranged as far afield as Brighton and Cambridge. These authors may have had ideological or practical reasons for the breadth of their definitions; the creator of London City Suburbs, Percy Fitzgerald, wanted to insist that a certain rural quality still pervaded much of London, for reasons I discuss in a later chapter, while Thorpe’s definition depended mainly on the extent to which a town was easily accessible from London by rail. Indeed, in writing of this period the use of the term “suburb” is somewhat idiosyncratic and possibly generational. When Collins describes an area west of Regent’s Park, east of Edgeware Road and south of St. John’s Wood as a suburb in Hide and Seek (1854), this is clearly based on the area’s having been considered a suburb ten or fifteen years prior, rather than on its built-up condition at the time of the novel. Similarly, Mrs. Riddell’s designation of the Chelsea area near the Thames as suburban in The Uninhabited House (1875) might not coincide with a younger person’s view of the space, when newer suburbs were being developed as far west as Fulham.

How, then, can we use the term usefully, for the very liminality of suburban space is key to its significance in much of the writing about it. If a space is too clearly rural or urban, reading it as suburban may very likely lead to stretching a point or misinterpreting the significance of a scene or setting. If an author himself or herself designates a space as suburban, should we take that at face value? Perhaps, but to do so may lead us to miss nuances or outright contention that would have been more obvious to contemporary readers. Fortunately, there are some common threads in many descriptions of suburban space that may lead us to a working (or workable) definition. First, many suburban spaces are characterized by evidence of physical, man-made changes to the landscape—this is very often represented as the residue of building, such as scaffolding, half-constructed housing, half-built new roads, “To Let” signs and the typical debris of construction. Sometimes, the changes are wrought not only by new housing developments but also, significantly, by railway construction, which was the single-biggest contributor to the scope of suburban growth in this period. These areas may be experiencing entirely new construction, or they may be pre-existing settlements that are preparing (or being prepared) for growth. So, one criterion for a working definition of “suburb” would be that there is new building activity that, to the observer, appears to be transforming the space from what it was to what it is yet to be; in other words, the suburbs are typically physically transitional spaces.

What differentiates suburban space from other transitional spaces, such as those constructions sites wonderfully documented by Lynda Nead in Victorian Babylon? As Nead so clearly demonstrates, construction was an unavoidable fact of London life due to the ...