![]()

SECTION 1

Why make a documentary film?

Images and written texts not only tell us things differently, they tell us different things.

David MacDougall

author of Transcultural Cinema (1998: 257)

We write to test our thinking, and the same is true when we film. A modern approach to social research requires us to think about human action through its affect, bodily sense and experience, and for this we need techniques that work in real time as well as those that operate retrospectively. We cannot know the experience of another person completely, even if we share the same time and space, because of the way that things feel differently for each of us. A filmmaker, however, seeks proximity to others as a way to interpret their thoughts, emotions and actions through images, sounds and stories that are eventually shared in a different but related cinematic experience. Opportunities for these documentaries are found in daily processes, spoken words and critical events, or they might be discovered outside of our existing conceptual frameworks as we encounter new things along the journey.

Filmmaking for fieldwork is more than using a camera and sound devices to gather data on location. It is about a collection of procedures and skills involved in cinema praxis that can inspire our thinking and transform our ability to understand the world. It is a simple method that relies on the belief that good construction material for a film can also provide rich terrain for growing new ideas, and as such it is informed by just two principles:

1 Knowledge is explored and expressed using techniques that operate at the level of sensory perception.

2 Ethical considerations about the lives and experience of others inform the style and approach of the work.

The emphasis of this handbook is on the practical and technical aspects of documentary filmmaking. However, in this section we will look at some theoretical ideas and their associated techniques that demonstrate the relevance of cinema practice for academic research. The text uses ideas that have supported the making of my own films in order to inspire readers to think about their reasons for using a particular filmmaking method. Equally, you may wish to reflect on an already established cinema practice where you are required to think about filmmaking in new ways.

In Argonauts of the Western Pacific, Bronisław Małinowski (1922) described how a wealth system based on the exchange of seashells informs the daily lives of island people, beyond their simple economic needs. The so-called ‘kula ring’ required that in order for shells to retain their monetary value they must be in perpetual circulation, which required various means of direct interpersonal communication. When this work was first published it presented an interesting alternative to a Western audience who were more familiar with depersonalised systems of hoarding capital in banks. Małinowski’s research ethics and findings were brought into question when his personal diaries revealed a colonial sensibility that is anathema to contemporary research, but his methods have survived to this day. During an extended stay on the islands of New Guinea, Małinowski developed an approach to understanding other cultures that he called ‘ethnographic’. This involved participating in the lives of other people, alongside a more detached, observational and academic analysis of their customs and practices. Filmmaking for fieldwork draws on this ethnographic tradition by using a camera and microphones to describe the ways that people become involved in and affected by processes, such as the kula ring, from a position of close involvement. It uses the procedure of narrative editing as an analytic tool, in order to explore ideas about the relations between people and objects, with the ultimate aim of developing documentary stories about the complicated feelings and emotions that extend from such intersubjective activity.

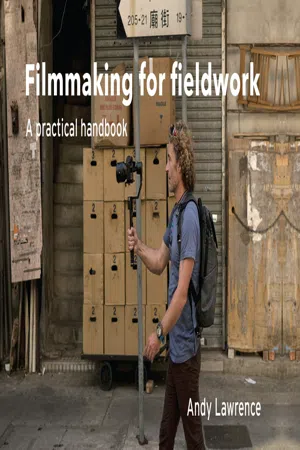

The author (right) consulting research participants about framing for his film, The Lover and the Beloved: a Journey into Tantra

Filmmaking for fieldwork is an empirical art where each stage of the method contributes towards the creation and adaptation of knowledge. Today people share films across the internet that have the potential to convey physical, emotional, performative and experiential aspects of social life in ways that other media cannot. However, filmmaking should not be seen as a way to merely illustrate people and practices, but rather as a means of ethnographic discovery. There is a general need for fieldwork techniques that can produce audiovisual material with the potential to extend our understanding, through the editing, towards whatever mode of storytelling is best suited to the topic. Fortunately, material that makes good research can also make a great film. The requirements of anthropology, for instance – a detailed understanding of the relations between people and things – also contribute the vital elements of filmic grammar. By using the camera and microphones to look closely at what is happening around us, we can begin to see how experience is woven through individual processes that combine strategic action with emotional feeling and their collective impact on our wider environment.

The words ‘film’ and ‘making’ were first used to describe how images are rendered in celluloid, but in an era of digital technology they have come together to denote a praxis that involves ideas, human experience and technique, as they are enacted and narrated through sound and image. In a filmmaking approach, the physical and interactive elements of cinema craft help a practitioner to look more closely at everyday situations. Some have suggested that a process of mimesis or enskillment happens when a research subject is engaged through a documentary filmmaking method. According to Christina Grasseni (2009), seeing is shaped, directed and attuned, instinctively and cognitively, by our physical and social engagement with our environments. In this sense, seeing and hearing are epistemic practices that shape and are shaped by our practices. It is not possible to represent a moment of fieldwork for all those involved because of the difficulty in sharing experience, but we can aim to evoke a sense of it through an illusion of proximity that might introduce others to our way of seeing. What we see refers directly to how we see, and thus perception and expression are in a relationship that is mutually influential. This is demonstrated to the audience of a film by our choice of camera and microphones, the way these are handled and how the associated images and sounds are used in the eventual narrative. Our own feelings are embedded in a film, coexisting with the sentiments of the people who are the main focus of the documentary work. The aim of ethnographic research is to explore these subjectivities and find balanced and nuanced ways to represent them. By looking closely at how emotion and intellect are expressed through strategic action we can even work with spoken languages that we do not fully comprehend, simply by following the emotion of a scene. By editing these recordings into an ethnographic story a filmmaker can explore how personal actions become social or political, and how experience reinforces or challenges a person’s ways of being in the world.

Writing field notes requires a reformulation of experience as it is happening. Experience as it is lived soon turns into experience as it is narrated. Ethnographic writing tends to happen on the margins of fieldwork events and it relies on the researcher to continuously conceptualise what is happening around them. A camera and microphone, on the other hand, work at the speed of light and sound, not only framing what occurs in front of the lens and around the pickup, but also preserving the embodied reactions of the filmmaker. In written ethnography our own emotion and sensitivities as they were recorded in the field can be edited in an attempt to create narrative coherence. In filmmaking ‘sentences’ are cast as the film is being recorded, and the personal and experiential cannot be removed because they overlap in each element of the recording.

Filmmaking and writing should not be set against each other – they should be seen as complementary practices. For example, the ethnographer Richard Werbner (2011) has shown that when filmmaking is undertaken before writing, a continuous re-engagement with emotive moments of fieldwork that have been recorded can help us to develop a more evocative and situated written ethnography. What is important for an ethnographic story is not that it attempts to tell the whole truth about something or someone, but rather that it aims to convey a sense of the lifeworlds of others. The relationships that eventual audience members create with the protagonists of a film then become something altogether new, ‘an experience’ entwined in the broader context of public viewing. In this way an audience contributes to the recreation of meaning through their own immersion in the film’s content. Filmmakers are encouraged to reflect on their work and develop written accompaniment to their films when necessary, but the primary mode of enquiry and the main output of the work can all be achieved through the filmmaking medium.

The intention in making my own films (Lawrence 2008, 2011, 2012, 2016) was to understand situations involving childbirth and death that arose through proximity and involvement. I was not assuming to know the experience of being born, giving birth or dying; rather, I wanted to receive wisdom from those who had made it their profession to be involved in these activities. Filming in the UK with midwives for Born (2008) encouraged me to engage with existential experiences that are aroused in childbirth, and this forced me to think about how to evoke this cinematographically. To achieve a successful birth, a woman must harness the fear that pregnancy can encourage and use this new-found ability to overcome obstacles in her path. Midwives help women deal with the uncertainty that childbirth brings about through coordinated action which requires long-term training and the use of specific techniques. I came to realise how similar the task is for ethnographic filmmakers working with the people they encounter in fieldwork situations. Throughout my travels with a camera I have found it necessary to evoke the way other people act and speak, summarise their actions and truncate their histories, and in doing so I have also considered my own part in their lives. I will attempt to convey some of the difficulties, as well as the pleasures, of this journey by using examples from my work.

Daniel He, appearing in the first public screening of British Born Chinese

Technique

A documentary film develops through a continuous process of analytic thinking and enactive recording, where new ideas are created with each interaction. Academic researchers who choose audiovisual methods to express their ideas encounter problems if there is a lack of recorded material available to describe their theory in a cinematic way. A filmmaker must record images and sounds that both support and generate ideas. If certain grammatical shots are neglected while in the field then it may not be possible to create effective new sequences later on when editing. This is an important difference between filmmaking and writing, where it is much easier to elaborate on actuality at the writing-up stage. In this section, I will describe some foundational techniques for recording and editing a film that can be applied equally well to research and documentary storytelling.

Describing human experience: the triangle of action

The moving picture makes itself sensuously and sensibly manifest as the expression of experience by experience.

Vivian Sobchack

author of A Phenomenology of the Film Experience

(1992: 3)

A filmmaker mediates between those who have first-hand experience and those who develop a related experience by watching the film. We cannot know the experience or bodily sense of another person completely because we cannot be that other person. However, it is possible to gain a proximity to others, and through this closeness or distance we can develop an understanding of how they feel. There are two quite distinct types of experience. ‘An experience’ that unfolds in real time requires different techniques for recording it than ‘narrated experience’, which is explicitly retrospective and presented according to a conceptual logic that is already pre-formed when we first encounter it in the field. At this gathering stage we collect evidence of experience as it unfolds through time and space in physical actions and processes – rather than evidence of how it is talked about after the event that developed the experience has taken place. This is how we show rather than tell an audience about what has happened. The late philosopher, Hannah Arendt, emphasised how meaning is created through subjective human actions and interactions, and in the same way, ethnographic films make use of processes to build an impression of what constitutes human action and the experiences that extend from it.

Films that are concerned with affect, bodily sense and experience often try to get close to their subject. The first and most pressing question when recording any film is where to direct the camera and microphones and how to move fluidly to gather the variety of shot sizes and compositions that are necessary to build the narrative of a film. O...