![]()

PART ONE

Education Goals throughout the

Edmistons’ Career

Before William Henry Sheppard cofounded the American Presbyterian Congo Mission (APCM) in 1891, he had already established personal and professional networks within several historically black colleges and universities in the United States. Most of the African American staff at the APCM were recruited through those networks and shared a sense of duty regarding outreach to the African continent. Part One shows how three institutions of higher education promoted the type of racial uplift ideology behind the early twentieth-century African American missions movement while also becoming the targets of efforts to alter or eliminate this style of Protestant ministry.

The explanation is guided by the chronology of how Althea Brown and Alonzo Edmiston established their lives at the APCM, starting with their connections to HBCUs. Chapter 1 analyzes some of the motivations shared by black missionaries from various denominations before detailing how the legacies of these missionaries helped enable Brown and Edmiston to move abroad in 1902 and 1904, respectively. In terms of their educational goals, 1908 was a pivotal year for the couple because they became the first of nine African American staff dismissed or retired from Southern Presbyterian foreign service during the denomination’s first two decades in central Africa. Chapter 2 places the Edmistons’ efforts to remain employed at the Congo Mission within the context of shifting theories regarding the roles of African American professionals in colonial societies. Major changes in the ministry duties of Brown and Edmiston through 1936 are explained as reactions to new denominational and political policies as well as partial conformity to the international rise of race-specific industrial and agricultural education. Part Two analyzes shorter periods during the careers of Brown and Edmiston in further detail.

![]()

1

Industrial Education and Symbolic Home Building in the Congo Free State, 1898–1907

By certain favors to the Bakuba, [Congo Free State officials] are also trying to prove to them that they are their real friends and we their enemies. However, this is exceedingly hard for them to do.

Althea Brown Edmiston, 1906

The marriage of Althea Brown and Alonzo Edmiston at the American Presbyterian Congo Mission was announced in the United States by a rumor. A newspaper article claimed that Brown was actually an anonymous central African woman who had convinced Edmiston to forsake his American habits. Since the article was attributed erroneously to a former missionary named Samuel Verner, his rebuttal (titled “Edmiston Did Not Return to Savagery”) became one of the first published accounts of how the couple intended to use their academic skills to establish a new family home. He described Althea Brown as a Fisk graduate who was “the equal in intelligence and character of any colored woman in America.” And Verner closed with an eyewitness account of the “splendid establishment built up by Edmiston’s energy and common sense” at the Ibanche station. He expected that the mission movement would benefit from more African American ministers like them.1

The testimony of this former employer of Alonzo Edmiston highlighted the combination of moral conviction, liberal arts training, and practical labor that became a hallmark of ministry for these two missionaries. But, as the rumor suggested, the contributions of Brown and Edmiston could remain obscured unless they adapted and publicized an appealing narrative. They found models for their missionary careers—and hope for future ministry support—among the alumni of historically black colleges and universities.

Around the turn of the twentieth century, two men were celebrated as the most famous African Americans in the world.2 One of those men founded Tuskegee Institute and became a champion of black industrial education. Booker T. Washington’s plans to promote the self-sufficiency of black Southerners through entrepreneurship gained additional recognition following his 1895 Cotton States Exposition address and his partnerships with white philanthropic organizations.3 The second-most famous man was his fellow alumnus from Hampton Institute, the Reverend William Henry Sheppard. He earned the nickname “the Black Livingstone” as a hunter, explorer, diplomat to a secluded African kingdom, and cofounder of the American Presbyterian Congo Mission.4 Sheppard’s intent to establish a thriving African American and central African Christian community in the Congo Free State was threatened by the regime of King Leopold II and by the race-based recruitment policies of Sheppard’s denomination.

Both men sought to defy literal and ideological boundaries in pursuit of a future that recognized the humanity and leadership potential of their race. This chapter explains how Althea Brown and Alonzo Edmiston planned to maintain that ambition into the next generation of Southern Presbyterian mission work. Like their mentor Sheppard, the couple tried to protect the employment opportunities of their African American colleagues and expand the unique projects they had pioneered at the mission. And, like Washington, they encountered both the recognition and problematic racial stereotypes that accompanied a reputation built on industrial education expertise.

For all the rhetorical emphasis on the practicality of industrial education, much of its appeal was grounded in abstract ideals. Washington promoted it as a path toward recognition, self-respect, and the eventual dismantling of racial discrimination. A statue at his institute celebrated the teaching strategy as an essential step in the abolition of slavery. Other industrial institutes and colleges touted themselves as cornerstones of self-help and racial uplift through innovation in various trades. And Yekutiel Gershoni attributes a mythical status to Tuskegee-style industrial education as envisioned by African enthusiasts in the early twentieth century, describing the development of its reputation as “a magic formula by which Africans hoped to bridge the gap between themselves and technologically advanced Europeans.”5 The teaching strategy promised to keep attention on tangible, reproducible steps for success without losing its element of faith in results not yet realized.

Within the American Presbyterian Congo Mission (APCM), industrial education plans advanced the ideological interests of certain African American missionaries even when they did not claim to use vocational curriculum officially. Three industrial schools in the APCM were founded on the basis of plans that originated with the Executive Committee on Foreign Missions. The mission station that most of the black missionaries claimed as their home base hosted the first industrial school from 1905 to 1908; Alonzo Edmiston served as its director. Four female missionaries also oversaw unofficial vocational programs for orphan girls that began at the Congo Mission about ten years earlier. These initiatives served the symbolic goal of promoting status and leadership opportunities—a cornerstone of historic racial uplift work. The historian James Campbell linked the image of the APCM stations as “vehicles for the introduction of Hampton-style industrial education into Africa” to William Sheppard’s experiences there. Campbell argued that, for Sheppard, a Hampton education “affirmed his faith in himself and his race.”6 Though the expectations for industrial education at the Congo Mission did not always originate with the African American Presbyterian ministers, this group shared a motivation unique to their context within a white-led denomination based in the American South. Incorporation of industrial education methods represented one way for the black missionaries to protect the place they considered their home.

In his analysis of the twenty-first-century black church, the theologian Walter Fluker defined home as a site where past injustices are met with acknowledgment and a plan to design a hopeful future. Historical memory provided the metaphorical location for the “home” built and preserved by continual efforts to respond to memories in innovative ways.7 The mission movement contributed to the symbolism of “home” in African American religious history by offering an additional outlet for ambitions to escape Jim Crow oppression. The fact that this outlet became reality for relatively few did not diminish its appeal or influence. The Ibanche mission station, with “the Black Livingstone” as its supervisor and a primarily African American staff, represented religious and political authority sustained through its connections to African leaders and to black institutions in the United States. More so than the physical location of Ibanche, this social network itself became the figurative home for African American Presbyterian missionaries. Industrial education served to strengthen that social network through the sharing of curriculum strategies and resources while recognizing the historic obstacles that had made these strategies necessary.

The men and women of African descent who joined the APCM as staff from the 1890s through the 1930s represented a spectrum of educational experiences. Five of the men (William Henry Sheppard, Lucius DeYampert, Henry Hawkins, Alonzo Edmiston, and A. A. Rochester) were graduates of Tuscaloosa Institute, a southern Presbyterian seminary later called for some years Stillman Institute and now called Stillman College. Edmiston and Sheppard had additional experience at institutions known for popularizing industrial education. Their ties to Tuskegee Institute and Hampton Institute, respectively, played significant roles in how their later ministry work was publicized. Two of the first African American women to join the APCM (Lucy Gantt [Sheppard] and Lilian Thomas [DeYampert]) attended Talladega College, a liberal arts–centered program founded by former slaves with support from the American Missionary Association (AMA). A sister AMA university, Fisk, offered a scholarship to Althea Brown and inspired her commitment to overseas ministry. Annie Katherine Taylor (Rochester) graduated from the all-black Scotia women’s college before committing to the mission.8 Joseph Phipps was the only African American missionary at the APCM to travel without experience at a historically black college or university; he attended Moody Bible College. And Maria Fearing was the first of this group to have her application to the Executive Committee on Foreign Missions challenged because of her educational background. Though she took classes on the Talladega campus, Fearing completed the normal school rather than the collegiate program.

The willingness of these black missionaries to cooperate in the mission field without respect to their academic differences signaled that they shared a concept of success atypical among ministers for a Presbyterian denomination. Most of the individuals described above were recruited by the Reverend William Henry Sheppard to help maintain the original Southern Presbyterian station in the Congo Free State and start a second one in 1898. Sheppard designed the Ibanche mission station as an outreach to the Kuba kingdom that was also a demonstration of his unique evangelization capabilities. His status as the first Westerner welcomed into the Kuba capital city, Mushenge, increased Sheppard’s confidence that he could also plant the first Christian ministry there with royal permission. The diverse educational experiences among this team of missionaries, all with this goal in mind, offered some advantages for drawing the attention of their African neighbors while also improving the Americans’ quality of life.

Industrial education methods brought early recognition to the African American female missionaries. Maria Fearing earned her salaried appointment to the APCM by providing room and board to orphaned girls. Her self-funded project continued to grow as an official component of the mission partly because the young residents worked cooperatively to complete domestic chores within the foster home. Lilian Thomas co-managed this Pantops Home and helped prepare Lucy Gantt Sheppard and Althea Brown to operate a similar program at the Ibanche station. As was the case at most other mission stations in the Congo Free State, the staff at the two APCM stations needed a pool of local laborers to help establish the infrastructure.9 But the foster homes stood out by treating domestic training as a community-building tool rather than just as individual acts of servitude for missionary households. At the Pantops Home, girls lived together in small households and performed their sewing, cleaning, and meal-preparation duties for each other. It was a style of domestic training reminiscent of the way that students completed chores in the Talladega College female dormitory, where Fearing had served as a matron.

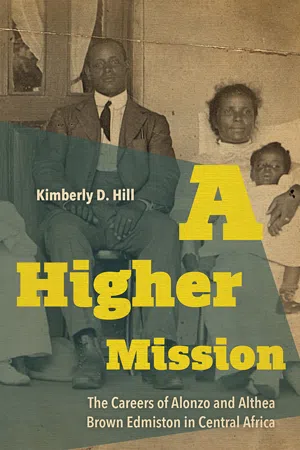

Figure 1.1 Portrait of Lucius DeYampert, Lilian Thomas DeYampert, Alonzo Edmiston, Althea Brown Edmiston, and Sherman Kueta Edmiston at the Congo Mission, ca. 1907. From the A. L. Edmiston Papers, RG 495, box 8, Presbyterian Historical ...