![]()

PART I

UNDERSTANDING SUPER MEN

![]()

THE SIMULACRUM OF HYPERMASCULINITY IN COMIC BOOK CINEMA

DANIEL J. CONNELL

When Jean Baudrillard released his prescient philosophical treatise Simu-lacres et Simulation in 1981, only two examples existed of blockbuster Hollywood superhero films: Superman (1978) and Superman II (1980). The notional simulacrum Baudrillard spoke of—a simulacrum being a world shorn of external references, disconnected from reality—was not related to Reeve’s Superman, given that Baudrillard’s main theory was that media culture was primarily concerned with interpreting and reflecting some hyperreal image not truly connected with reality. Reeve, an excellent athlete after whom the Sportsmanship Award at Princeton Day School’s invitational hockey tournament was named, stood 6 ft. 4 in (1.93m) tall and was by all accounts an outstanding physical specimen. Although he did weightlifting with David Prowse (of Darth Vader fame) and added some 30 lbs (14kg) to his frame in preparation for the role, the base was already there: someone at the pinnacle representing someone at the pinnacle.1

Reeve’s Superman fit in perfectly with Orrin E. Klapp’s analysis regarding popular models of masculinity: “The purpose of hero-worship behaviour seems to be to convert a selected individual to an ideal, a durable symbol of supernormal performance—to capture and make a norm of the exceptional.”2 Where Klapp’s research on popular heroes in the 1950s reflected and preceded archetypes like Reeve’s Superman, Baudrillard’s theories attached themselves via the work of Lacan to a world he saw as unraveling at an increasing pace just after Reeve’s debut.3 What is fascinating about the intertwining events—the first true superhero blockbusters and Baudrillard’s theories of hyperreality—is how they set a groundwork that would not truly reveal its connectedness until far later: the year 2000.

Perhaps the delay occurred because of the need for technology—explicitly CGI—to develop further so that audiences could be convinced of a fantastical world’s reality. Or, maybe the explosion and long death of the muscleman action film, peaking with Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger in the mid-1980s to the early 1990s, delayed the financial imperative for studios to invest in developing superhero films. What is clear, however, is that the sustained era of comic book cinema can be defined as having started with 2000’s X-Men—produced by Richard Donner, who had delivered us the son of Krypton twenty-two years prior. Twentieth Century Fox’s foray into the genre set off a continued burst, eventually leading to the creation of two distinct cinematic universes: those of Marvel and DC. What had been sporadic releases such as Reeve’s Superman, the Tim Burton–directed Batman series, or even Wesley Snipes as Blade, cemented into a more consistent, viable genre with the release of X-Men.

What connects X-Men and Baudrillard? In short, two hypers: hyperreality and hypermasculinity. Hyperreality denotes the inability to distinguish reality from a simulation of reality—which, Baudrillard argues, leads us inexorably towards the simulacrum. Hypermasculinity, on the other hand, can be defined as the exaggeration of stereotypical male behavior, such as feting of physical strength and aggression over emotional intelligence and empathy. Part of this “macho” image is founded on being effortlessly muscular and imposing in stature. Comic books—from Action Comics #1 onwards—provide a clear intersection between hyperreality and hypermasculinity, given as they are to presenting dramatically masculine physicality. And yet, the intangibility of comics—that inevitable removal from reality caused by the need to represent rather than to replicate—presents a rather neat buffer to the issue of hyperreal culture, creating a need for something we do not have or want. A person may temporarily wish to fly like Superman or have his physical proportions—but, presented as they often are, this notion is fantastical rather than definable as actual longing. In the context of comic books, a person cannot become the physical iteration of the superhero. Where this becomes a fascinating prospect is when the medium shifts to that of film: here the superheroes are, by and large, represented as flesh and blood. The buffer is removed, and the audience can see (or perhaps might see the physical potential of) themselves within the source material. Now Baudrillard’s Phases of the Image become important considerations:

Such would be the successive phases of the image:

It is the reflection of a profound reality;

It masks and denatures a profound reality;

It masks the absence of a profound reality;

It has no relation to any reality whatsoever:

it is its own pure simulacrum.4

This sequence is the journey into hyperreality, a space with no referentials, which is known as a simulacrum. In the evolution of comic book cinema, the physical manifestations of hypermasculinity have denatured a profound reality (male physicality in its average guise) and traveled through Baudrillard’s phases as a natural evolution.

In view of this phased development, the boundaries of hyperreal hypermasculinity will be bookmarked by the first and purported last iteration of Hugh Jackman’s Wolverine: X-Men in 2000 and Logan in 2017. In time, the nature of the genre is likely to become even more hyperreal. With this in mind, it is important to note the attempts—conscious or otherwise—of the earlier superhero films of the twenty-first century to ground themselves notionally in a form of realistic interpretation. This section will focus on the Fox and Marvel Studios films, as the DC Cinematic Universe will be discussed elsewhere in this volume. For the sake of brevity and clarity, this chapter will mostly avoid discussing large ensemble films—for example, the Avengers series or Captain America: Civil War (2016)—and will largely focus on the physical manifestations of hypermasculinity instead of on behavioral elements. The focus can thus remain on a key attribute which, as Erica Scharrer noted in Experiment, creates a scenario whereby “hypermasculine males exhibit extreme and exaggerated forms of masculinity, virility and physicality.”5 The journey from exaggeration to simulacrum is most potently examined through the representation of masculine physicality.

BECOMING HYPERMASCULINE

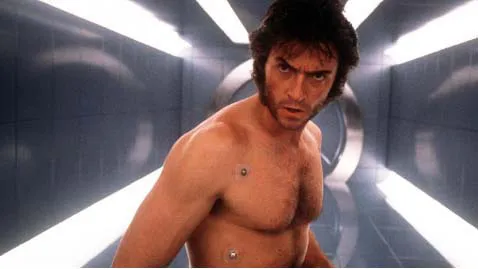

When Jackman first appeared as the adamantium-augmented superhero Wolverine, he was thirty-one years old. Though tall at 6 ft. 3 in. (1.9m), he lacked a particularly muscular physique—in direct contrast to the comicbased, 5 ft. 3 in. (1.6m), burly character he was hired to play.

In this initial iteration, Jackman bears all the hallmarks of a heteronormative, idealized Western Everyman: tall, slim, fit, conventionally good looking. The animalistic and brutal nature of his character are presented through mannerisms rather than raw physical presence. He does not provide a truly realized corporeal manifestation of the comic book figure. What is fascinating about this image—and a hallmark of the genre’s relationship with physical hypermasculinity—is that somehow, seeing the transformative journey Jackman has taken and the subsequent popularity of the extreme muscular look, Jackman does not look quite right in this picture. He has not truly become Wolverine—which is bizarre when one considers that X-Men is his first and one of his most successful outings as Logan.

Hugh Jackman as Wolverine in X-Men (2000) © 20th Century Fox

This Everyman physical quality already begins to distort in the early 2000s. Spider-Man (2002) stars Tobey Maguire as the eponymous hero. There is a famous scene where, having been bitten by the radioactive spider, a gaunt Peter Parker slumps into a feverish sleep, only to wake empowered and bulked up. He stares at himself in the mirror, visibly confused at the overnight appearance of a six pack. What is fascinating about this transformation is that it represents the actual (what actors have to go through to complete these roles) and the virtual (a clearer iteration of the comic book original). In a 2007 E!News article, Maguire reveals that he received the role only after stripping down to reveal his physique—which suggests that the super-skinny Parker was an effect enhanced either by visual tricks or CGI.6 The genre is set on a hypermasculine path: actors need to prepare for their roles to substantiate the dimensions their characters inhabit on the page. This trend instigates an era of quasi-hypermasculinity, signified by Jackman’s increasing muscularity in the same role for 2003’s X2, and the hiring of younger, fitter men in roles such as Superman (Brandon Routh) in 2006’s Superman Returns or the Human Torch (Chris Evans) in 2005’s Fantastic Four.

“SOMETIMES, YOU GOTTA RUN BEFORE YOU CAN WALK”

What Maguire’s transformation scene also sets in motion is the standard requirement in the genre to show, usually in topless scenes, the effortless hypermasculinity of the characters. In some films this is not a surprise. Chris Hemsworth’s Norse god Thor, for example, would be expected to have a suitably classical heroic physique. Henry Cavill’s Superman should probably look like he can hold up an oil rig if that is what he is doing in the film. However, the pattern becomes odd when it does not seem to even correlate with the nature of the character. Take, for example, Benedict Cumberbatch’s Dr. Strange, who has magical powers, or Paul Rudd’s Ant Man, who is a master thief with a special suit that makes him microscopic. Even Robert Downey Jr.’s Iron Man seems to have bulked up by the time of 2010’s Iron Man 2, even though his superheroism is derived from his intellect and from technology, with a robotic body that allows him to embody the heroic body without needing to physically possess muscularity. These developments indicate an acceleration through Baudrillard’s phases of the image: though the genre may have, in small instances, suggested a reflection of a profound reality (that the Everyman could, perhaps, become a superhero), it very quickly moves on to the second phase—the masking and denaturing of a profound reality. These men, edging into the hypermasculine realm, represent an Everyman that does not truly exist. The slim, injured Tony Stark of 2008 came to resemble more the physique of someone with superpowers in 2010—all while still devoting most of his time to refining his reactor technology. Stark’s Everyman quality is masked by his new physique and denatured by the very fact that he seems to maintain it with no effort at all.7 This perversion is driven by the innate conflict between the two desirable drivers of the genre: to get as close as possible to the source material and to appear relatable to its core audience, which has consistently been men aged 18–35.8 There is a sense of impossibility when it comes to balancing these two conflicts: one cannot have the wondrous, transformative nature of the comics while also presenting these heroes as merely above average.

There is also the question, once the pattern of actors hiring specialists to condition their physiques is established, of professional pride: to be a superhero, post–Maguire Spider-Man and Jackman Wolverine, actors have the pressure of knowing they need to look the part. What this presents is homogenous athletic hypermasculinity, where even characters who do not rely on physical strength look like they work out. Paradoxically, scenes showing any of these characters working out are quite rare—though it could be argued that due to his corporate responsibilities, philanthropy, playboy lifestyle, and crime-fighting duties, moviemakers need to show audiences how Batman maintains his physique. Hence, we see him work out in both the Christian Bale and Ben Affleck iterations. Yet he is very much an isolated figure among the current representations of film superheroes.

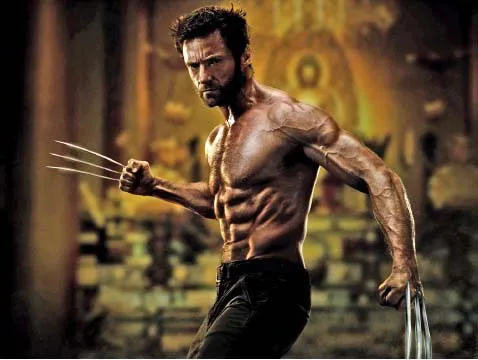

Where this masking and denaturing of a profound reality takes root is in its lack of care for what it presents: actual humans as effortless comic book characters. It is no surprise that, when one searches online for “Hugh Jackman Wolverine workout,” pages and pages of hits show up. It is an ephemeral ideal presented on screen, so tantalizing, since we know this person is real, he exists, and he did something to make himself look this way. The profound reality—the tenet that the Everyman in each character reflects a more universal possibility of heroism—has been denatured into a quest to replicate this hypermasculine totem of heroism: the physical intertwined with the moral. Never mind that these actors are paid to look like these heroes. Never mind that they have months, and hours per day, and teams of experts supporting them, to create what is largely a temporary result. Millions of people across the globe want to be like the Wolverine they see on screen, even if Hugh Jackman himself does not look like that six months after filming has wrapped.

ABSENCE OF A PROFOUND REALITY

Of course, one would have to believe in the innate ability of the Everyman to be heroic to even think such a thing could be denatured. It certainly seems as though the genre itself believes so: perhaps because the comics industry was born out of an audience’s desire to see transformative goodness in its heroes, which creators assume to be a desired reflection of potential in oneself. But, if that is not true and there is no profound reality of potential good, the image comes to reflect this absence. Take what Mike Ryan, Jackman’s trainer for The Wolverine, had to say about their preparations:

When we were building Hugh up for the Wolverine movie, we got a call from Baz Luhrmann who was directing Hugh in the movie Australia. Baz said, “Come on, guys, back it off! He’s getting too big.” And you can see Hugh getting bigger in the film. In Wolverine, Hugh looks big onscreen, but really he’s just ripped. That’s the secret to looking good. It’s not just about getting big, it’s about getting ripped.9

Hugh Jackman as Wolverine in The Wolverine (2013) © 20th Century Fox

The fantasy of one film is ruined by the construction of another. This discrepancy belies the lack of profundity in outcome or result. Luhrmann and the film he is trying to create is irrelevant, because the dividing line has now dissipated. The image is now for, and only of itself: Jackman has to look like this because he is the Wolverine. His complete integration with the character now means that not only is there no Everyman within, but the suggestive connection between source material and audience is also lost. To think one could be Wolverine from the comics is fantasy; to think you could be Jackman, by the time X-Men Origins: Wolverine (2009) and The Wolverine (2013) were rele...