![]()

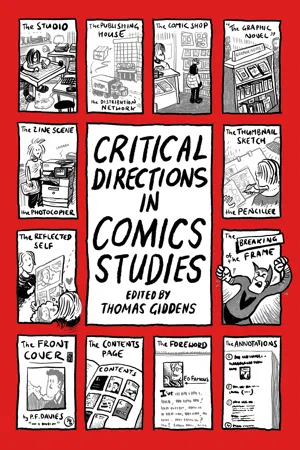

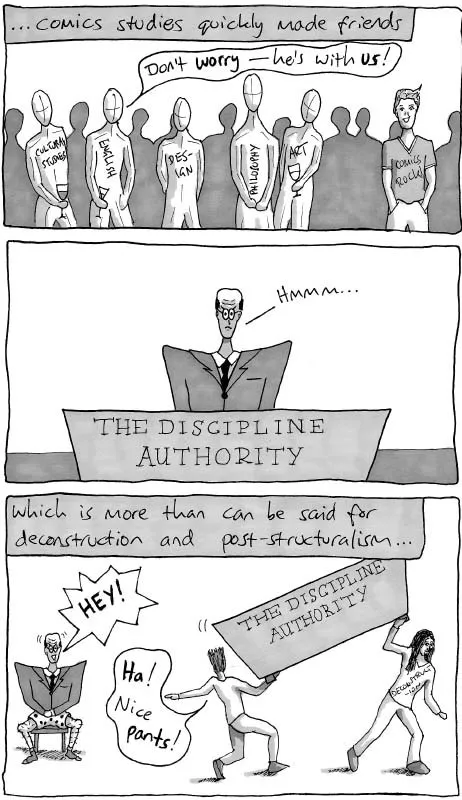

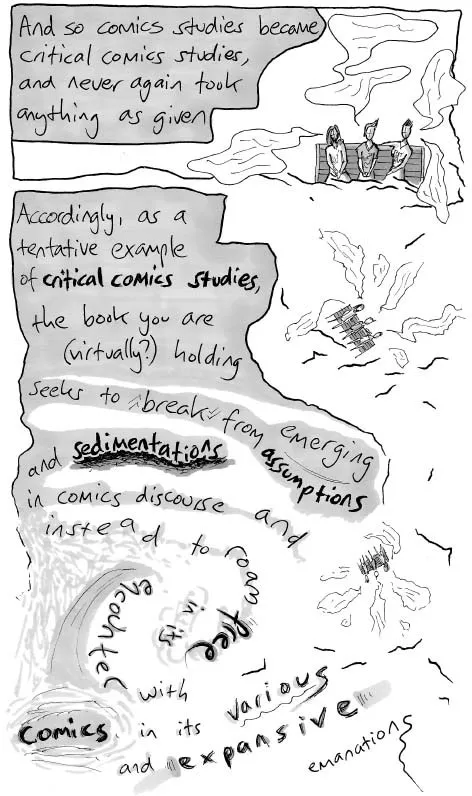

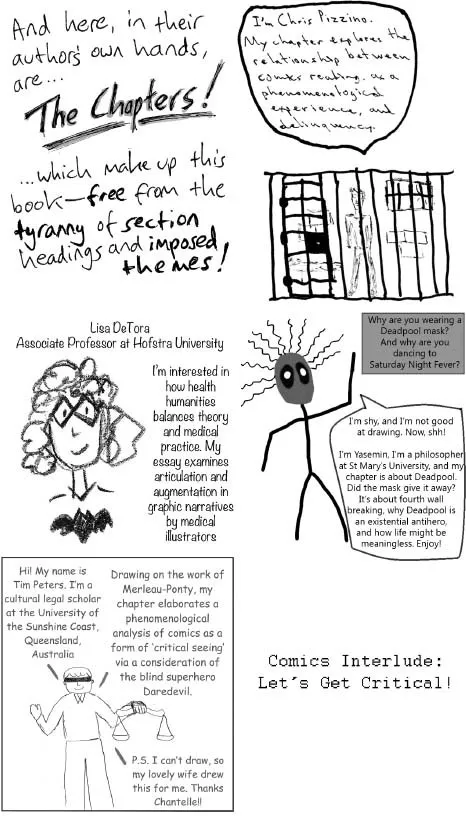

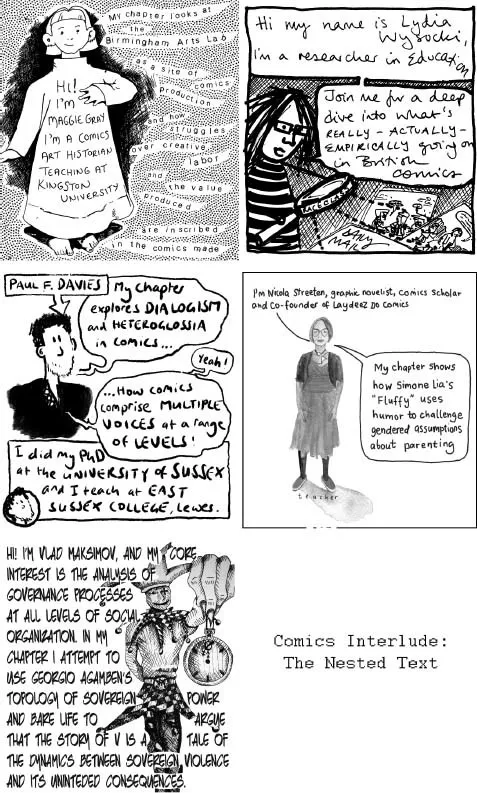

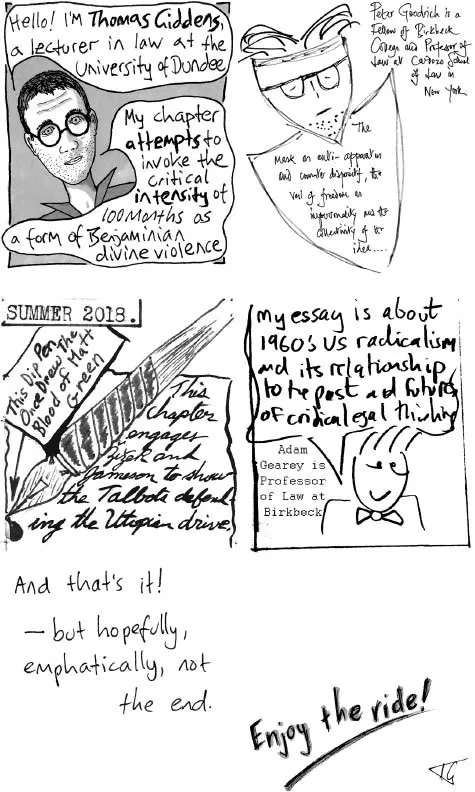

COMICS INTERLUDE #1

Critical Comics Studies

An Origin Story

BY THOM GIDDENS

![]()

1

On Violation

Comic Books, Delinquency, Phenomenology

CHRISTOPHER PIZZINO

The time is the mid-1950s; the place, any town in the United States. A group of boys meet in the woods to read and swap comic books. Fixating on stories that show violence tinged with sex, they scan pages with interest and then with excitement. One boy leaves the ragged circle of his fellows. Producing a pocketknife, he begins to stab a tree, grimacing in agitation as thrust follows thrust. A second boy rises and, grabbing a broken brick, smashes it against a rock; moments later, he considers using it to crush a third boy’s head. No adults are present to witness this scene of savagery and social collapse—only the kids and the comic books that seem to be destroying them.

There were, of course, quite a number of adults on hand for this moment, since they were filming it, using child actors, for a segment of the news show Confidential File (Kirshner 1955). This well-known instance of anticomics propaganda was broadcast a year after the 1954 Congressional hearings on comic books as a cause of juvenile delinquency, which had resulted in the formation of a new Comics Code Authority.1 The segment’s effect on existing anticomics stigma may have been minimal. What Confidential File put on film already existed in the writings of midcentury anticomics crusaders, and thanks to the extensive strictures of the new Comics Code, the fate of comic books in the United States had already been sealed. Yet this scene offered a concentrated image of widespread fears about the comic book’s power to take hold of the mind and the body, and to make the comics-reading subject delinquent.

Comics studies has not yet grasped what this infamous tableau of savage young comics fans could reveal about comic book reading today.

I offer this scene as a powerful image of the phenomenology of comic book reading—and it is revelatory, in part, because it is paranoid and distorted. The distortion, which links comics reading to delinquency, has not been and currently is not correctable by a simple adjustment of terms, nor by more seemingly respectable categories of comics such as the literary or highbrow comic, the graphic novel, and so on. Perceptions of comics as delinquent have certainly diminished over time, but separate names for more “literary” comics will not end such perceptions. To understand why this is the case, we must grasp the medium’s link to delinquency with a fuller sense of how it touches, and is touched by, phenomenological experience specific to comics.

I employ those aspects of phenomenology most concerned with sense experience and its relation to embodied subjectivity, as explored by Maurice Merleau-Ponty ([1945] 2012). Although phenomenological studies (in the sense just delimited) of the visual arts are numerous, their focus is almost invariably on fine arts expression, and there has been no sustained investigation of the phenomenology of comics reading. In beginning a pursuit of this fugitive concern, scholars can, I hope, be excused for paying serious attention to anecdotal evidence. Pascal Lefèvre (1998) takes this approach in his paper “Recovering Sensuality in Comic Theory,” which cites, among several striking recollections from comics readers and creators, this anecdote from Thierry Smolderen concerning his childhood experience with a sequence from the Franco-Belgian Western comic Blueberry:

I spent hours reading and reading again the whole sequence.… I almost felt the comic book vibrating in my hands … my eye perceived this image, my body received it like a whiplash, but my mind stayed paralyzed.… What drives me to scrutinize the images of contemporary comics is [ … ] the palpitating perspective to understand intellectually one day what seems to be by essence destined to escape me forever. (2, bracketed ellipsis in original)

The susceptible viewer of Confidential File’s segment on comics might, of course, take this anecdote as further proof of comics’ destructive effects. But I see the disturbance young Thierry Smolderen felt as the emergence of a robustly embodied reading experience, a “palpitating perspective” found not in the “vibrating” comic book itself but in its phenomenological relation to the eye, body, and mind of the reader—most especially in the context of comics as an illegitimate art.

One of the reasons discussion of phenomenological matters has not been copious in comics studies is that, as Ian Hague (2014) notes, “materiality as a whole remains a relatively neglected area of comics scholarship” (23). In its earliest years, comics studies made little space for phenomenological approaches to comics, though the occasional revelatory excursus—notably from Charles Hatfield (2005, 58–64) and from Roger Sabin (1993, 52)—indicated possible approaches to comics reading as embodied experience. More recently, the issue of embodiment has been more likely to arise in relation to comics creatorship, often with an eye to the way comics can be read as traces of bodily marking.2 This newer inquiry does not necessarily exclude the question of reading; indeed, its discussion of how readers experience comics as traces of a creator’s body can offer better understanding of cycles of comics creation and consumption.3 Thus far, however, this line of investigation has not prompted much consideration of even basic haptic aspects, tactile and visual, of comics reading as such.

When such consideration does arise, there is a persistent focus on sites marked as haptic in the narrow sense, i.e. clear visual references to the tactile, such as images of the author’s hand in autobiographical or other nonfiction comics.4 Such sites often are indeed revealing vis-à-vis questions of embodied reading; I will presently discuss a related kind of haptic self-reflexivity in Kyle Baker’s Nat Turner (2008). But our understanding of the significance of such sites is likely to be limited if not made part of a larger surround so that many aspects of comic book reading can be understood phenomenologically. Karin Kukkonen’s (2015) brief discussion of page design in relation to the reader’s body schema points in this direction, but a more thoroughgoing approach is needed (61–63). My object of focus here is the reader holding and held by her comic book, fixed in a disciplinary gaze that cares little how the comic was produced, or by whom, but that is certainly ready to treat the reader with suspicion. We must conceive of comics reading in terms of ongoing phenomenological processes that do not necessarily originate in creatorship, that do not need clear visual denotation to be in effect, and that are strongly tied to comics’ delinquent status.

To bring this conjunction of phenomenology and status concerns into focus is to discover hitherto unseen complexities in the dynamics of comics reading. The new critical direction offered here for comics studies offers a deeper—and hopefully less defensive—understanding of how comics reading can be affected, continuously and intimately, by the problem of illegitimacy. This latter problem is quite familiar to comics studies, but typically it is detached from phenomenological concerns, not least because scholarly understanding of comics history has, for the most part, developed separately from understanding of comics form. Early theorists of comics in the United States knew well that the medium as it has existed historically—loved by fans but often disrespected, infantilized, treated as disposable, and threatened with censorship—and comics form in the abstract might productively be seen as unrelated matters. In his founding theoretical work Understanding Comics (1993), Scott McCloud addresses this difficulty while discussing his own thought process as he developed his ideas about the medium: “Sure, I realized that comics were usually crude, poorly-drawn, semiliterate, cheap, disposable kiddie fare … but—they don’t have to be!” (3). Such an approach is scarcely neutral in relation to status questions, since it asserts that comics deserve to be taken seriously, if only for their often-unrealized potential. But drawing out this potential, for McCloud, means valorizing comics form as largely separate from comics history.

History and form have sometimes been in conversation with one another in the work of later scholars. In some cases, their purpose has been to shed light on the historical roles that particular kinds of comics have played; in other cases, the goal has been to understand how the particular formal mechanisms of comics emerged historically and developed over time. Both projects have tended, directly or indirectly, to reiterate McCloud’s assertion that the medium deserves respect—though now for the historical roles it has played as well as for its artistic power. Thus, for comics theorists, questions about the relations between form and history have been shadowed by status concerns that are difficult to avoid and that affect not only terms and concepts but also basic orientation to the object of study. In short, the goal of understanding comics’ specific historical conditions and formal manifestations is subject to the constant gravitational pull of another goal: making comics less illegitimate.

What I am describing is arguably endemic to the study of illegitimate genres and media, and it strongly distinguishes the history of comics studies from that of scholarship devoted to more legitimate art forms. Studies of major modern literary genres such as the novel, or of dominant modern media such as film, tend to assume that questions of history and of form naturally enrich one another—indeed, that historical trajectory and form are a fated match. When first developing a sense of the novel’s identity as a genre, scholars readily perceived the growth of the novel in the volatile conditions of modernity and its highly self-reflexive formal qualities as mutually complimentary; much the same can be said for the rapidly changing historical conditions in which film emerged relative to its particular technological and formal properties. Such understandings of history and form are, of course, inseparable from the legitimacy of the object of study.

A theorist of comics might well envy this state of affairs, since the relation between the medium’s history and its formal and material features is fraught wherever comics have been harshly condemned and designated culturally “low,” as in the United States.

Indeed, comics history and theories of comics form are mutually implicated around dynamics of violation—of literary and artistic norms, and of morals and laws—quite different from the principles of social and political coordination typically believed to be in effect for the novel or film. When phenomenological concerns enter the picture, these dynamics only become stronger because, as will be increasingly clear, comics violate the mind-body relations considered normative for the act of reading. In focusing on this dynamic of violation, I consider the comics reader as a subject whose body, since the advent of the comic book, has a primary place in the history/form relation. I do not consider comics history in terms of an abstract timeline of economic, formal, or stylistic changes; nor, obviously, do I consider comics form apart from its relation to the act of reading. Rather, both history and form here take their primary orientation from the fact that the comic book reader has a richly embodied relation to the comic book itself, and a likewise complex, and more troubling, relation to the disciplines and institutional forces that have designated comic book reading as suspect. In other words, the comics-reading subject exists at the intersection of immediate sensory experience and large-scale disciplines and structures of power—of phenomenology and Foucauldian concerns, as it were—in ways that are specific to this medium and to its history.

Let us then confront a single difficult fact that remains mostly unaddressed in discussions of the history/form relation: when the medium was most embattled in the middle of the twentieth century, anticomics discourse seized upon its material features and its distinct way of interacting with readers’ bodies as fundamental to its damaging effects. In short, the phenomenology of comics reading was central to the medium’s delinquency. Most attentive to this fact thus far has been Jared Gardner (2012), who emphasizes the open, participatory nature of comics reading, which was objectionable to midcentury critics of literature and the fine arts alike. “Within postwar art criticism,” Gardner observes, “the emerging aesthetic ideal privileged the work as complete … appealing to the viewer’s logic and not to bodily experience or personal emotions…. The comic, with its formal and inescapable demands for active completion by the reader, is therefore a most predatory aesthetic object” (80). For New Critics and most other midcentury intellectuals discussing the comic book, its “predatory” tendencies were incurable; “The popularity of the comic book certainly suggested some kind of mass mind control, which the well-made poem and the well-tuned critic stood ready to resist” (81). To understand the depth of New Critical aversion to comics reading, we must trace the relation of this “mind control,” as understood by anticomics discourse, to the specific “bodily experience” of holding and reading a comic book.

The attitudes of postwar art critics Gardner discusses were, in some ways, simply a concentrated version of the animosity that had arisen in response to comics almost from the start. For most of the twentieth century, contempt for comics trumped sincere scholarly curiosity about them; attempts to understand the medium were often inseparable from beliefs that comics contributed to illiteracy, or criminality, or various kinds of delinquency. This explains why psychologist Fredric Wertham, the most influential anticomics crusader of the twentieth century, has sometimes been named a key early theorist of the medium; Wertham’s focus on how young people read comic books was, if strongly biased, at least serious inquiry of a kind. But as we will see, Wertham’s writing also expresses the revulsion that motivated even—or especially—the most intellectually respectable anticomics discourse, and that shaped the ways it figured or imagined comic book reading.

An additional glance at the anticomics segment of Confidential File will begin to indicate the precise target of this revulsion. In the staged scene discussed earlier, there is a strong focus on the haptic nature of comic book reading; several close-ups show the boys’ hands swapping books with eagerness and agitation prior to the climactic moments of potential violence. The rapidity with which the boys swap their comics parallels the swiftness with which they translate violent images into action, and the scene as a whole suggests exactly how the “mass mind control” feared by critics was seen to work (Gardner 2012, 81). Comics were perceived as transmitting a kind of zombie plague, seizing control of motor function and consciousness and then propagating, in the real world, the violence their pages displayed.

Such an image of comics was not randomly sensational. In fact, it was quite well attuned to a key factor that likely made midcentury intellectuals more opposed to the comic book: its intentional, coordinated activation of eye and body in the act of reading. As Garrett Stewart (2010) notes in his discussion of book theory, the “routinization of books as objects of consciousness” in modernity has become so complete that reading—a physical process involving sustained interaction with a fairly complex material thing—can be understood as a purely mental activity; for the modern reader, works of printed literature seem oddly to “inoculate against response to their own physical format” (437). For midcentury New Critics, as Gardner (2012) argues, such inoculation...