![]()

1

Pursuing a Portrait

Subject, Object, Method

Room A

In November 2003, I went to London to see a painting that I had been thinking about for over a decade (Plate 1). It is the work of the Venetian artist Gentile Bellini, produced in 1480 at the Ottoman court in Istanbul, and it depicts Sultan Mehmed II, long known to both Turks and Europeans as “the Conqueror”—a name given out of admiration on the one hand and fear on the other. This disjuncture embodies everything I have come to know about Gentile’s portrait, starting with its reputation. For despite the picture’s fame, I had to travel underground to see it, into the basement of the National Gallery to “Room A of The Lower Floor Collection.” Officially open for only two-and-a-half hours on Wednesday afternoons, this collection was also accessible by special request. I arrived on a Friday and sought out the Duty Manager’s Office, where I was told to come back the next morning for admission.

The geography of the museum should have alerted me that this was a second-rate space for what were considered second-rate paintings. The experience of climbing a grand staircase to reach a collection’s masterworks is familiar to museum-goers worldwide. One virtually never travels down to view a museum’s most precious holdings unless perhaps there is a figurative treasure hunt involved, such as the exploration of an Egyptian “tomb” or a chance to see an archaeological find in situ.1 Located on the Lower Floor of the National Gallery, Room A literalized a sort of class hierarchy that seemed thoroughly and appropriately British. Although the Main Floor galleries were numbered, this one was lettered. Location and lexicon warned me: this is not where you will find our Leonardos and Rembrandts, our Constables and Turners. You are straying off the beaten path if you venture here, into the uncertainties and doubts of art history, where we cannot guarantee the quality of visual experience that is the hallmark of the National Gallery. Indeed, Room A displayed paintings that museum professionals would call “problem works”: works with significant questions of attribution or even authenticity, works that had at some earlier date been cleaned or restored nearly to the point of defacement, and those that simply did not live up to the considerable standards of the Gallery’s world-class collection.

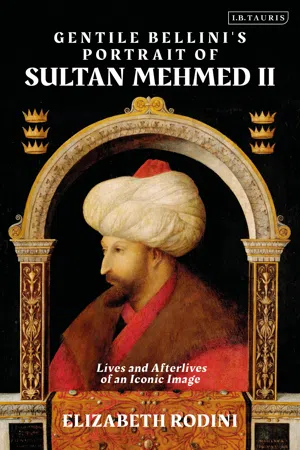

Gentile Bellini’s Portrait of Mehmed II fits that bill, no matter how well known its subject or intriguing its imagery. This is evident as soon as we start to examine the picture closely. It seems at first glance a view in profile—the pose favored for portraits on ancient medals and coins, and preferred well into the mid-fifteenth century (Chapter 2, Figures 2.4 and 2.5)—although, on closer inspection, we can see that the Sultan is actually turned ever so slightly toward us, permitting us to glimpse the bridge of his nose and a bit of his right eye. Recognizing this, we begin to see the third dimension described in the work: furred robes animating the Sultan’s curved shoulders, the bulbous turban wound round his head, and an architectural frame given volume through shading on the inner arch and the adjacent marble ledge. The ledge separates us from Mehmed and is another familiar Renaissance portrait element, used to suggest space by seeming to distance the sitter physically from the viewer. On its base, to left and right, are inscriptions glorifying the subject and the painter—Mehmed is called “conqueror of the world” and Gentile his “golden soldier.” The date of the completion of the painting anchors this timeless representation in a particular moment: 25 November 1480.2 A neatly draped tapestry, embroidered and studded with gems, rounds out the pictorial illusion, keeping us back while simultaneously inviting our touch.

The harder we look, the more contradictions emerge, insisting that something about this picture is not quite right. There is the contrast between the crisp details at the margins, of tapestry and carved stone, and the relative illegibility of the sitter himself, his face hazy and his form lost under a bundle of ill-defined robes. Then there is the marble arch that surrounds him. Its role is monumental, yet it seems flimsy, as though one good push could topple it over; it appears to curve up over the Sultan’s head, yet his body remains firmly situated behind it. The overall relationship of figure to architecture is also disconcerting, as if the picture of the Sultan were cut out and pasted behind the carved frame. It is hard to describe or define the space he occupies. Is he sitting before a black background affixed with six crowns? Or is blackness a sign of empty, open space? In that case, do the crowns—themselves enigmatic, possibly emblems of territorial domain, possibly marks of Mehmed’s position in the Ottoman dynasty3—float, like specters or some sort of proto-holographic illusion? How do we explain this lack of clarity from a skilled and much admired Renaissance painter?

One response has been to dismiss the picture as damaged and unfit for close examination. Its condition is poor. It has suffered from overcleaning, aggressive repainting, and other mishandlings. Scholars have a hard time agreeing on what Gentile Bellini painted and whether we can even consider the portrait to be by his hand. It has in past decades been unattributed to Gentile then reattributed to him. It has been considered a copy of Gentile’s original as well. Most recent opinion seems settled on its authenticity, although many experts concur that less than 10 percent of what we see can actually be given to Gentile. All of this uncertainty makes people who work with art—scholars, curators, conservators—uncomfortable. To assign a work to an artist and make arguments based on a problematic attribution is risky business if it is going to be reassigned to someone else tomorrow. Similarly, details of appearance, like the kind of visual disjunctures described here, can easily be discounted as irrelevant to the original work.

The problematic reputation of Gentile Bellini’s painting certainly disturbs the National Gallery, which in 2009 sent it on long-term loan across town to the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), where it now hangs, among carpets and metalwork, in a gallery dedicated to cross-cultural exchange in the fifteenth century. In this context, Gentile’s journey to the Ottoman court is the dominant concern; the painting’s presence has less to do with its essence as a work of art than the larger circumstances that it represents, less for what it is than what it stands for.4 Here the paradoxes also multiply: the story of the portrait spans continents but its art historical narrative is restricted by uncertainties over its own past; it is in great demand but is shunned; it is highly relevant but frequently dismissed. The portrait’s short journey across London, its resettlement and reassessment at the V&A, are a sharp distillation of a larger, more compelling challenge: how best to tell the story of objects valued for their permanence but defined by change.

Between time and space

When I look at the beleaguered surface of this painting, the aspect that landed it in Room A, I see not a damaged picture but an artifact of survival, and I think of my research as an archaeological project as much as an art historical one. The painting displayed today in London is certainly not the painting that originally was; there is a metaphoric excavation to be undertaken here, allowing that which time has diminished to tell us something of what has been lost—something that, I would venture, was of considerable quality. We allow this with all sorts of objects: with ancient columns fallen from their plinths, medieval sculptures that have lost their polychromed surface, fragments of pots, and jewelry that can no longer be pieced together. But we demand more of paintings, not permitting the ghosts of images or the reworkings of well-intentioned but ill-informed restorers into our notion of what a painting “is.” With X-rays, ultraviolet imaging, and other modern means, however, we have an excellent sense of Gentile’s original composition that, it turns out, is essentially identical in form to what we see today, down to the inscriptions on the parapet. Arguments about the painting made on the basis of its original composition, on what is represented and how it is arranged, are strongly grounded in visual evidence of authenticity.

A critical loss in the case of the London portrait is its surface, and so the traces of brush and paint that make this a work, quite literally, of Gentile Bellini’s hand. In a world in which authorship is of central importance to the prestige of a picture and to its monetary value, this fact is a significant strike against it. But from the perspective of history writing, we can work around it—even with it, allowing the absence of pigment to redirect our attention and reframe our inquiry. Other paintings by Gentile survive in better condition, so we can begin by imagining that his picture of the Sultan originally exhibited similar qualities of precision and luminosity.5 This is a chapter of its physical history that is not difficult to reinvent and suggests that the Sultan portrait, produced, after all, for a high-ranking and certainly demanding patron by one of the most admired Venetian artists of the day, was once of fine quality itself. Rather than the history of a second-rate picture, ours is the story of a fine work that time has transformed.

Indeed, the stripped surface we see in London, flat where modulations of color have been lost and murky where Gentile’s sharp edge of observation has been worn away, tells a different tale, a harder one to trace but ultimately a more captivating one. This is a history not of painter making but of time transmuting, not of a picture hanging on a wall but of a canvas that has journeyed across time and space, from then to now and there to here. Its worn surface is an invitation to ask questions about what happened after the painting was completed. What events have intervened in this picture’s life to make it lose its sheen and sharpness? Where has it hung, who has seen it, and how have they responded? What is the story of the picture beyond the relatively static moment of its production? What happens if we put it back in motion?

Recirculation is the principal project of these pages. By this I intend several things. Most literally, the chapters follow Gentile’s portrait of Mehmed as it traveled from its place of production in Istanbul westward, eventually arriving, although not permanently, in London. There are periods in which we can pinpoint its place of display and time-stamp its ports of call—on an easel overlooking the Grand Canal in Venice, for example, or in a crate at Victoria Station—each context framing a new set of meanings. For nearly 400 years of its history, however, its location remains a mystery, with only a few tantalizing hints as to where it may have been. In this context, recirculation is also conceptual, referring to the impressions Gentile’s picture made not only through its physical presence but also on the imagination.

My pursuit of these varying historical traces grows out of several interlocking areas of interest for art historians and other scholars who write about things: mobility on the one hand, and object biographies on the other. In many ways, Gentile’s portrait of Sultan Mehmed exemplifies a history of cross-cultural encounters firmly situated in a “contact zone,” a place of convergence that invites diverse modes of inquiries into how and why it was made and used. A long line of distinguished art historians has taken this cosmopolitan approach to the portrait, and their work—singling out that of Gülru Necipoğlu and Julian Raby, to which I am particularly indebted—reveals the complex circumstances of its production. Yet that contact zone, the Ottoman court, represents only a brief chapter in the life story of the portrait. Gentile’s canvas has been on the move for half a millennium, its path running the length and breadth of Europe. To echo cultural critic James Clifford, the question that interests me is not so much “Where is it from?” but “Where is it between?”6

Quite literally, the “between” is the trajectory spanning the painting’s production at the worldly court of the Ottomans and its current home on the walls of the V&A. More abstractly, “between” addresses the meanings it has held along the way, from Mehmed’s solicitation to Venice for the loan of a painter to the portrait’s enshrinement in art historical narratives as the first realistic representation of a Turk. Attention to the “between” encourages us to build out from more...