![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

The Southern Slav Question

Mark Cornwall

In 1914, many people living in Austria-Hungary – the vast conglomeration of lands that stretched across East-Central Europe as the Habsburg Empire – expected that Franz Joseph, their eighty-three-year-old monarch, would soon die, to be succeeded by the fifty-year-old heir apparent Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Some anticipated the latter’s accession as Emperor Franz II with optimism, others with anxiety. He was rumoured to have a radical reform programme in mind, but he was also notoriously reactionary and nurtured deep resentment against anyone he felt to have damaged the prestige of the Habsburg dynasty. This accession to the throne of course never took place. For on 28 June 1914 in the Bosnian capital of Sarajevo it was Franz Ferdinand who died, murdered along with his wife by the Bosnian Serb, Gavrilo Princip. It was the old emperor Franz Joseph who survived and who a month later led the Habsburg Monarchy into a disastrous European war which would cost the lives of a million of his subjects.

The significance of the Sarajevo assassination was recognized immediately by those contemporaries who knew what was really at stake. In Vienna on 28 June, Josef Redlich recorded in his diary, ‘This day is the day of a world historical event … the fateful hour of the Habsburg approaches.’1 In Prague, the Czech university professor Josef Pekař greeted his students dressed in black, observing that the death of the Habsburg prince had damaged the Monarchy in ‘deep and unforeseen ways’.2 Others in the public eye agreed that there were bound to be very unpredictable results from the ‘ghastly end of the heir apparent’.3 Some in hindsight would claim to have predicted an inevitable war, even if they were not clear whether Austria-Hungary would be enmeshed in a Serbian, a Balkan or a European conflict.4

Most historians would agree with Vladimir Dedijer, still the leading chronicler of the assassination, that ‘no other political murder in modern history has had such momentous consequences’.5 Proverbially, as every school pupil knows, it was the spark that ignited the First World War, the trigger that led on to mass slaughter. Not surprisingly it has produced ever since a huge historiographical industry, embracing myths, hypotheses and partisanship – what exactly happened, why it happened and who was really responsible.6 After the collapse of the Habsburg Empire in 1918, there were always some who eulogized Franz Ferdinand as a hero and martyr for the dynasty.7 Others – not least some Serbian historians – portrayed him as a warmonger and tyrant who had even been planning the war of which he was the first victim. It was a debate reactivated around 2014 on the centenary of Sarajevo, when some Serbian academics strongly objected to the work of Christopher Clark who, in portraying the Serbia of 1914 as a ‘rogue state’ in the Balkans, had implied that their country too bore some responsibility for the catastrophe.8 It is clear then that, with the myriad perspectives on ‘Sarajevo 1914’, the controversy over it will take a long time to die.

Yet this focus on the spark itself has often obscured the more significant underlying tinder that the spark ignited. Behind Franz Ferdinand’s demise lay the intricate context of the Balkans, that European region which observers by 1914 had variously constructed as exotic, chaotic and barbaric.9 For many contemporaries the Balkans was also synonymous with the intractability of the so-called Southern Slav Question. As one historian has vividly argued, this late imperial era was in fact an ‘age of questions’; politicians or commentators regularly asserted that some social or geopolitical issue was of international significance, demanding a speedy solution if it was not to escalate and cause havoc.10

The ‘Southern Slav Question’ was one such thorny problem. In essence, it meant the suggestion widely discussed in European educated society that the South Slav peoples – notably Serbs, Croats and Slovenes – could or should be fused together into some new territorial unit. Any student who wishes seriously to explain the Sarajevo assassinations has to navigate this South Slav labyrinth and will soon realize that there was no one Southern Slav question. There were numerous interpretations of what it meant, and numerous ‘correct’ solutions being proffered on all sides. That it was portentous and needed a solution, however, was clear to anyone in authority. Writing just a month before Franz Ferdinand was killed, the Viennese newspaper Reichspost (always close to the archduke’s thinking) warned that among the many problems facing the Monarchy ‘the Southern Slav has become the greatest danger’; it needed to be fixed calmly but energetically.11 Reminiscing much later, one Hungarian politician would stress the decisive role of this Southern Slav Question in causing the Great War; it was, he added, ‘a thoroughly prepared, consciously and systematically directed political action’.12

As this suggests, to some contemporaries there was a sense of real momentum and purpose behind the Southern Slav project. There seemed to be something organic, something inevitable, about the rise of a modern South Slav (Yugo-Slav) nation to challenge the existing geopolitical order. The Habsburg regime based in Vienna increasingly saw this as a fundamental threat to its existence. After all, in the 1860s, the empire had lost most of its Italian lands and its German sphere of influence, thanks to the creation of new national Italian and German states sponsored by Piedmont and Prussia respectively. In the wake of those disasters, Austro-Hungarian foreign policy from the 1870s turned to focus on south-east Europe – the Balkans – but immediately encountered there the rising nationalist states of Serbia, Montenegro and Romania (each of which secured full independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1878).

The Habsburg elite was increasingly anxious that Serbia in particular would be another Piedmont.13 For it was well known that Serbian rulers had long aspired to expand their territory into Bosnia or even Croatia, incorporating the large Serb diaspora and recreating a ‘Greater Serbia’ in the Balkans. Partly to anticipate that national advance, Austria-Hungary in 1878 managed to occupy the Ottoman provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina and thirty years later annexed them in the face of fierce Serbian opposition. Until the mid-1890s, thanks to an Austro-Serbian alliance (1881–95), Vienna had successfully managed to rein in a restless Serbian kingdom and reduce it to a satellite state of the Monarchy. But thereafter, under its last Obrenović king, Serbia became increasingly erratic in its foreign policy and suspect in its intentions. In the early years of the new century a prosperous and liberal Belgrade would also become a mecca for many Serbs or South Slavs from the Habsburg Empire who were dissatisfied with conditions at home.14

But in the Habsburg mindset we must note, too, a deeper international dimension to Serbia’s instability. The warning, sounded back in 1870, that Serbia might one day become a stalking horse for Russia seemed to be ever more credible.15 For a century, Austro-Russian rivalry in the Balkans had caused international crises – indeed, it was at the heart of the so-called Eastern Question about the fate of the Ottoman Empire. If Russia managed to gain overwhelming influence in the Orthodox states of Serbia or Montenegro, then a Russian noose would begin to tighten around Austria-Hungary. Montenegro was always a potential Russian satellite; from 1900, Serbia also seemed to be drifting in that direction. It was a geopolitical nightmare for Vienna, conjuring up the wild possibility that Russia would eventually control the states bordering the Habsburg Monarchy and even gain access to the Adriatic Sea.16

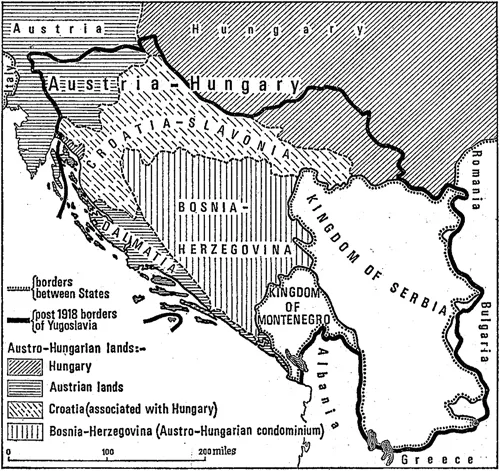

In this light, for the Habsburg elite, the Southern Slav Question was largely synonymous with the menace of a Greater Serbia. Belgrade seemed to be pushing a nationalist agenda that threatened the very standing of the Monarchy as a European Great Power. Hawks in the Habsburg army like Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf (chief of the general staff) duly felt that only a military solution would pre-empt Serbia’s ambitions and force it back into its correct satellite status. Yet a potentially more constructive solution did also beckon after 1900.17 For by the twentieth century just as fundamental for the Habsburg Monarchy was the question of whether its own domestic South Slavs might be fused into some new national unit, allowing Vienna (not Belgrade) to dominate the Southern Slav agenda. To this as a solution, however, the emp ire’s very structure presented a major obstacle. For in 1867 through the empire’s dualist system, the Monarchy had been divided into two halves – Austria and Hungary.18 It was a division that cut straight across the Southern Slav lands, allotting Slovene territories and Dalmatia to Austria, while Croatia and a substantial Serb population were left within the Hungarian half of the empire (Figure 1.1). The annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1908 added more Serbs and Croats to the empire and theoretically implied that some Southern Slav unit ‘within’ would be viable. In fact, it brought another layer of complexity, for the new provinces were not subsumed into Austria or Hungary but treated as a colony, a corpus separatum with their own governor and a special ministry supervising them from Vienna.19

FIGURE 1.1 The South Slav (Yugoslav) lands in 1913.

It was therefore an enormous challenge (or headache) for any Habsburg statesman to solve the Southern Slav riddle, particularly since the Hungarian regime in Budapest was absolutely wedded to the dualist system. But we should emphasize in turn the multifaceted interpretations of Southern Slav unity which also exacerbated any resolution.20 To many intellectuals in the southern Habsburg lands, it was never about achieving Serb unification, but a case of some ‘Greater Croatian’ or ‘Yugoslav’ vision. The stance of Croat nationalists for decades had been to join Habsburg South Slavs together in one Greater Croatia with Zagreb as the capital. The core territory of Croatia-Slavonia would be united again with Dalmatia and Bosnia, and perhaps even the Slovene lands. Thereby they would fulfil that historic crusade for Croatian ‘state right’ (the pravaši ideology), recreating a fully sovereign Croatian territory. ‘Trialism’ would be the result: the dualism of Austria-Hungary converted through a special Croatian unit into a trialist empire.

Parallel to this Greater Croatia was a distinctly ‘Yugoslav’ interpretation of trialism and the Southern Slav Question. Its adherents promoted the unity of Serbs and Croats within the empire on an equal basis, and with a progressive agenda of social and constitutional reform. A wholly new and modern nationality was said to be emerging, characterized by civic inclusivity rather than the nationalist exclusivity of a Greater Serbia or Greater Croatia. Popular particularly in Dalmatia due to the vibrant example of the Italian Risorgimento, this ‘Yugoslav’ approach to the Southern Slav problem gained ground especially after 1903. A new generation of younger politicians created a Croat-Serb Coalition of sympathetic political parties in Croatia and Dalmatia, loosely allied across the dualist border and seeking a ‘New Course’ for the new century.21 In retrospect it was perhaps the most idealistic of solutions, for it worked from the assumption that linguistic unity – a common language between Serbs and Croats – would make inevitable a successful fusion of the two peoples into one modern nation.

In the years leading up to 1914, this ‘just solution’ was championed by many youthful idealists across the region (including Gavrilo Princip himself). A notable enthusiast too was the British historian and commentator, R. W. Seton-Watson. In his classic work The Southern Slav Question (1911), Seton-Watson emphasized that ‘Croato-Serb Unity must and will come’. He prioritized the rough linguistic uniformity of the region over any historic diversity: ‘a homogeneous population, speaking a single language, has been split up by an unkindly fate into a large number of purely artificial fragments.’22 In his view, a natural unstoppable evolution was occurring towards Serbo-Cr...