![]()

1 FASSBINDER’S MUSE AND ANTI-STAR, 1967–74

As Fassbinder’s seductive and enigmatic anti-star, Schygulla captivated German critics and audiences with an early screen image of corrupted naivety. This nascent persona – at times innocent siren (e.g. Katzelmacher), at other times debased proletarian vamp (e.g. Love Is Colder than Death, Götter der Pest/Gods of the Plague [1970] and Whity) – manifests itself in characters ranging from prostitutes to nightclub singers and servants; all figures with petit-bourgeois aspirations who dream of escape and happiness until disillusionment leads to betrayal and revenge. Before international critics would acclaim her as the ‘New Marlene’ in the 1980s, German critics perceived her more like a home-grown Marilyn Monroe pastiche – a ‘ Vorstadt Marilyn/backstreet Marilyn’1 whose streetwise femininity was associated with the working-class tenement blocks and dank courtyards of districts situated just outside the city centre.2 Schygulla’s evocative image not only appealed to critics and film historians but, with its overall tone of disillusionment, powerfully resonated with the failed utopianism experienced by the post-1968 generation.

Given the success of this persona, a key issue for consideration is whether Fassbinder was the flamboyant Svengali ‘author’ of it all. Was Schygulla merely one of his puppets or, alternatively, was she his muse and inspiration, guiding him on? Most reviewers and academics have, at least implicitly, located their assessment of her somewhere along this spectrum, considering Schygulla’s career through the dominant Fassbinder prism. As this chapter will demonstrate, the actress was indeed at times a willing puppet on Fassbinder’s strings, perceiving that such a role could be advantageous to her career. At other times, however, she maintained her independence and agency by working with a number of different German directors, extending her acting range and expanding her career prospects. I will argue that this was a mutually beneficial professional relationship from the outset, with Schygulla actively shaping her emerging star persona while Fassbinder simultaneously developed his auteurist style and vision.3

A scene in Rio das Mortes captures some of the complexity of their relationship. Here, Hanna (Schygulla) is seen in a bar dancing in a clinch with a stranger (Fassbinder) to a very slow blues number. Then, when the music changes to Elvis Presley’s upbeat ‘Jailhouse Rock’, they dance separately, with Fassbinder merely standing upright, nodding his head and clapping stiffly, while admiring Hanna’s solo dancing. Schygulla’s whole body gyrates, her hands and arms waving wildly in the air, her face animated by a series of continuously changing expressions, her eyes half-closed and lips wide open, mouthing and pouting. By breaking free and expressing her personality rather than the character’s, the actress revealed a side to her that Fassbinder admired but which was at some distance from his own conception of her screen persona. Twenty-five years later, Schygulla would recall this scene as ‘a moment of total liberation!’4 Thus, her dancing and laughter illustrate that while lascivious somnambulism was the most pervasive aspect of her acting style in Fassbinder’s films, there also existed an undercurrent of disruptive vivacity that could not be accommodated in their work together. The scene anticipates the inevitable rift between Schygulla and Fassbinder. While the Fassbinder roles may have constructed a coherent screen persona for Schygulla the star, they failed to offer Schygulla the actor the means of self-realisation that she increasingly craved (as will be discussed below).

The formative period with Fassbinder: experimental theatre and New German Cinema

Born in 1943 in Kattowitz in German-occupied Poland, and daughter of a timber merchant, Schygulla fled with her mother in 1945 to Munich. Her father, a prisoner of war (POW), only joined them in 1948. Subsequently, she went to grammar school, spent a year as an au pair in Paris and then, with the aim of becoming a teacher, studied German and Romance languages at Munich University.5 Around 1966, while still studying languages, she started taking lessons at the professional Fridl-Leonard acting school, where she encountered Fassbinder. However, apart from rehearsing some scenes together, both recalled that they had little contact and seem not even to have liked each other. Schygulla soon got bored, lost faith in her acting ability and left after a few months, apparently without too much regret. However, Fassbinder also (and contradictorily) claimed later that it was there and then that he had identified her as his future star: ‘As if I’d been struck by lightning [it became crystal clear] that Hanna Schygulla would one day be the star of my films, … she would be an essential cornerstone possibly, maybe even something like their driving force.’6

Schygulla returned to acting in autumn 1967 when Fassbinder tracked her down, offering her a last-minute replacement leading role in Sophocles’s Antigone, directed by Peer Raben and probably inspired by The Living Theatre’s performance of the same play.7 Although she only had a couple of days to rehearse before playing her part to the acclaim of the audience and critics, Fassbinder remembered her first public stage performance as an outstanding achievement, ‘magnificent, of extraordinary pathos and intensity’,8 and it was acknowledged as such somewhat begrudgingly by the collective. Subsequently playing key roles for the Action-Theater and the renamed anti-teater,9 her training as an actor was on the job. She recalls that critics liked her performances, perceiving her as ‘a mixture of artifice and naivety, both somnambulistic and dilettantish’10 – terms which later came to describe her performance style.

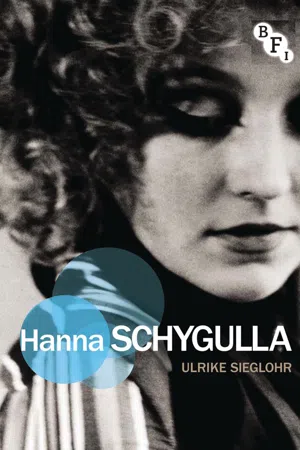

Schygulla continued to work with Fassbinder as he moved into low-budget film-making in the late 1960s while still directing radical political theatre. Off stage or off screen, she was pretty rather than strikingly beautiful: of average height, slim but with solid thighs and small breasts, she had big blue eyes, high cheekbones, a broad forehead in an expansive face with a longish pointed nose, wide, full, sensual lips, small, even teeth and a strong chin. A mass of curly blonde hair softened her features to resemble her teenage screen idols Brigitte Bardot and Marilyn Monroe. On screen, careful shading would sculpt her bone structure to break up the fleshy expansiveness of her pronounced Slavic features, while lighting, along with make-up, was key in enhancing her round facial contours, focusing on the eyes and lips while masking the dominance of her nose. ‘Curly hair and kohl rimmed eyes, something between a doll and silent film diva of the Munich backstreets’11 is Schygulla’s own description of her image at this time.

To understand the forces shaping Schygulla’s image, it is important to place her theatre and film work with Fassbinder within a broader political and cultural context. The late 1960s in West Germany was a time of counter-cultural activities, student rebellion and general political upheaval. In this context, specific cinematic state cultural policies resulted in financial assistance, giving radical left-wingers and inexperienced film-makers the opportunity to make films. The New German Cinema,12 as the movement became known, first developed domestically in the 1960s, but by the mid-1970s, auteurs such as Fassbinder, Werner Herzog and Wim Wenders were gaining international prominence. Conceived as a national cinema and underpinned by a cultural notion of film-making, New German Cinema distanced itself from the market values of both Hollywood and contemporary mainstream German cinema. In West Germany, the New German Cinema found favour primarily with radicalised students, producing a select but devoted audience.

Fassbinder’s Love Is Colder than Death, which starred Schygulla (see below for more detailed analysis), was one of the first feature films released by this new generation of film-makers, and, indeed, the aesthetically eclectic and politically radical New German Cinema’s body of work is unthinkable without Fassbinder. This is partly because of the highly idiosyncratic stamp he brought to his films and partly because the New German Cinema – also known in German as Autorenkino13 – like that of its predecessor the French New Wave, privileged its directors.14 Thus, Fassbinder, as director and creator of meaning, became the star and a marketing brand name from the start, with Schygulla increasingly regarded in early film reviews as his muse and non-commercial (anti-)star. In the words of one critic, the director was its ‘heart, the beating, vibrant centre of [it] all’.15 However, to extend the metaphor, without Schygulla as his leading star, Fassbinder’s oeuvre would have lacked the life-blood vital to this heart.

Fassbinder’s status as the iconic star director of the New German Cinema impacted directly upon Schygulla’s developing star persona. With his flamboyant and uncompromising identity (political and sexual), Fassbinder quickly became the focus of media attention rather than his much more reticent star. His confrontational manner with journalists and his excessive lifestyle of drugs, alcohol and upfront promiscuity (gay and bisexual) were easy fodder for the tabloid press, as they were at times for the broadsheets, being frequently noted in press coverage of his films. Fassbinder quickly acquired an iconic image, with his recognisable features (round face, high cheekbones, slanted eyes, prominent nose and full lips) and his regular attire of battered leather jacket, trilby hat and tight trousers. In addition to this distinctive image and self-conscious ‘enfant terrible’ persona, he also made frequently Hitchcock-like cameo appearances in his films, even starring in a number of them. Most of all, since his early films were known to be autobiographical in a ‘roman-à-clef’ sense, he knowingly exploited his private life for publicity and promotional material. Given the combination of Fassbinder’s media ubiquity and Schygulla’s intense desire for privacy during this period, it would have been near impossible for the actress to develop an equally striking star persona. Interestingly, when she finally did overshadow him, he took revenge (see Chapter 2).

Alongside a commercial West German star system, from the 1970s on, the government-subsidised New German Cinema developed its own star system as something distinct from the earlier generation of film-makers, such as the members of the 1960s Young German Cinema, who had tended to use lay actors.16 Although actors often remained closely associated with one particular director,17 they also contributed to a pool of performers who were easily recognisable across the body of New German Cinema. An individual actor would bring their previously accrued persona (achieved through the kind of roles they had played for one director) to their parts in other film...