- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

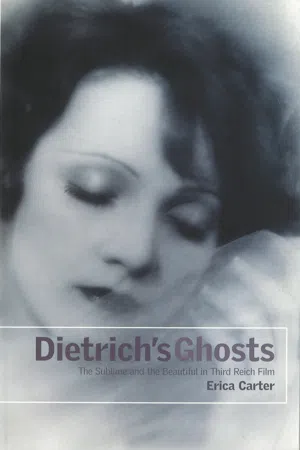

About this book

This text looks at the star system under the Third Reich. Following the experiments of Weimar, much of cinema after 1933 became part of a wider Nazi backlash against modernism in all its forms. This study contributes to contemporary debates concerning the historical study of film spectatorship.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dietrich's Ghosts by Erica Carter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Film as Art: A Cinema of Personality

When the National Socialists seized power in Germany in January 1933, the nation’s film industry was in a state of commercial and cultural crisis. Already ten years earlier, currency reform and changes in quota law had shaken the economic foundations of German film production by exposing the industry for the first time since the end of World War I to serious competition from abroad. The advent of the sound film in the late 1920s further destabilised an already weakened industry. The total costs of the transition to sound – which included for example the re-equipping, or sometimes the wholesale rebuilding of studios, restaffing with new personnel, the refurbishment of film theatres, and rising costs for the production of export copies – have been estimated at between 50 and 55 million Reichsmark for the transitional period 1927–8 to 1932.1 The prospects for recouping figures of this magnitude from box-office takings, moreover, were slim. In the depression years of 1929 to 1932, audience figures in Germany declined by an estimated 25 per cent, producing a ‘wave of company liquidations’ in the period immediately preceding Nazi rule.2

Helmut Korte’s conclusion, in his study of the feature film in the last years of the Weimar Republic, is that the National Socialists in 1933 encountered a ‘severely financially weakened and . . . largely compliant film industry that . . . looked to the state for decisive intervention, indeed for “salvation”’.3 That perception is certainly supported by accounts of the first major public encounter between regime and industry, a meeting that took place on the occasion of Goebbels’ speech as newly appointed Reich Minister for Propaganda and Popular Enlightenment in the Berlin Kaiserhof on 28 March 1933. Goebbels’ address to an audience comprising ‘prominent figures from all sectors of the film industry and filmmaking’, as well as a vociferous band of activists from Alfred Rosenberg’s Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur (League of Struggle for German Culture), was preceded by obsequious welcoming speeches from key film industry figures. Carl Froelich, whom we will meet again in his capacity as film director later in this chapter, spoke in the Kaiserhof as President of the Dachorganisation der deutschen Filmwirtschaft (Umbrella Organisation for the German Film Industry: DACHO). Froelich named 28 March as a ‘memorable day’ in the history of German cinema, marking as it did the first public commitment of a German government to ‘the art of film’. Apparently more contentiously (there are reports of heckling), Ludwig Klitzsch, Director-General of Ufa, promised a ‘willingness to cooperate’ on Ufa’s behalf, while the Nazi Adolf Engl, representing the Reichsverband deutscher Filmtheater (Reich Association of German Exhibitors) – an organisation that had, in his words, ‘always considered itself a mediator of cultural values’ – committed German exhibitors to ‘championing’ the ideas of the new state.

Opening speeches at the Kaiserhof event, then, emphasised the need for cultural and aesthetic transformation within the context of the Nazi state as prerequisites for the revival of German film. That these contributions were mere scene-setting for the Reichminister’s entrance (the trade journal Der Film called the opening speeches ‘dry’ in both content and form) became evident when Goebbels himself finally took to the podium.4 His initial naming of ‘the current crisis’ as ‘ideal’ not ‘material’ in nature was, admittedly, hardly innovative. Attempts at an idealist reform of the film medium dated back to the cinema reform movements of the 1910s and 1920s, and had found echoes in late Weimar debates over film-as-art versus film as commerce or kitsch. But Goebbels galvanised his audience – Der Film reports rapturous applause – when he reframed these older categories of film-aesthetic debate within a more emotive opposition: art versus danger. ‘I want to use a number of examples,’ he began, ‘to show what it is that makes a film artistic, and what makes it dangerous’.5

In Third Reich film historiography, Goebbels’ speeches are often used to preface studies of policy shifts within the broader scenario of Nazism’s ever tighter political and ideological control of German cinema. To this purpose, the Kaiserhof address lends itself well. It is among the earliest public records of Goebbels’ intention – phrased here, with characteristically treacherous understatement – to ‘intervene’ in the film industry and to ‘regulate’ the ‘effects’ of film in its more ‘dangerous’ manifestations.6 The rapid Gleichschaltung of the industry, the racial and political purging of film personnel that this entailed, the revision of film legislation (the 1920 Reichslichtspielgesetz) to make provision for pre-production censorship alongside the already generous censorship privileges accorded to the German state: all this was presaged, albeit often in the vaguest of terms, by the Kaiserhof speech.7

In what follows, however, I want to focus on a second and often critically underestimated aspect of the Kaiserhof event. When, towards the end of the speech, Goebbels recognises film as subject to ‘the inner laws of art itself’, this is more than mere sophistry, a ploy to disguise his (undoubtedly malign) ideological intent. This demand for an aesthetic rebirth of German cinema – a demand that found echoes in all areas of film-cultural debate through the 1930s – was certainly on one level what the film historian Klaus Kreimeier terms a ‘rhetoric of legitimation’ for the state-controlled film industry of the Third Reich.8 At the same time, as I seek to demonstrate in this book, the transformation of aesthetic practice to which Goebbels and others ‘rhetorically’ aspired was also a material and determining element in the Nazis’ achievement of state control in the arena of film.

In the opening four chapters, then, I proceed from an assumption borrowed from Walter Benjamin, which is that what was historically innovative in National Socialism was its forging of an intimate bond between aesthetics and the political.9 Benjamin’s contention was realised, I will argue, in Third Reich film through a variety of transformations in film production and reception that aimed to establish German cinema as the apotheosis of Nazism’s new national popular art. The Nazis’ organisational restructuring of German cinema through the 1930s is commonly assumed to have occurred in two stages. In the first phase, covering a four-year period roughly from 1933 to 1937, the Nazis’ attention focused on extending state control of the industry through a combination of organisational restructuring (Gleichschaltung), state funding via the Filmkredit-bank, political and racial purging, tightened censorship and other measures. In a second phase, the emphasis shifted towards the establishment of a state monopoly through a gradual, and initially covert, nationalisation of the industry via the Cautio Treuhand trust company.10

In each of these phases, however, as I seek to show, restructuring at the level of political economy went hand in hand with cultural policies designed to realise Goebbels’ goal of a rejuvenated film art. That the state functioned after 1933, not merely as a repressive apparatus exercising totalitarian control over the film industry, but also as the source of a series of generative measures designed to stimulate modes of artistic production that were consonant with fascism’s aesthetic aims, is demonstrated, I will argue, by numerous policy initiatives from mid-decade on, including the promotion of creative practitioners to powerful managerial positions within the industry, training initiatives to bring on a new generation of creative personnel, and interventions into exhibition practice designed to mould public taste to the shapes and patterns of an (apparently) quintessentially German film aesthetic.

Again, Goebbels’ speeches are illuminating here. In his 1937 address to the Reich Film Chamber – an annual event in which the Propaganda Minister reviewed past ‘progress’ and specified future plans – he presents his own vision of a two-phase development in Nazi film policy after 1933 when he asserts:

The task that faces us now is no longer organisational in nature. Last year, I was able to demand that artists be made members of company boards. Easy enough! The year before that, I could demand that scripts be ready at an earlier point, and that production continue throughout the year . . . The year before that, I could say, ‘We must raise box office figures by 50 or 60 million.’ This is hardly difficult! But this time around, we face programmatic demands of an artistic nature.11

Goebbels has already specified earlier in this address the force on which he will draw to meet the ‘programmatic’ artistic demands to which he now gives precedence: ‘Even in film, as in all other fields, it is true to say that any work can in the long term be sustained only by personality. In the long run, it is towering, fascinating and magnetic personality that sustains film.’12

The ‘programmatic’ restructuring of German cinema as a high art form from the mid-1930s on was to pivot, then, around the ‘towering . . . personality’ as its fulcrum and centre. What then are we to make of the concept of personality mobilised here? What are its origins, its ideological ramifications, and it specific role in ‘sustaining’ the art of film?

FILM, PERSONALITY AND GENIUS

Though there has been extensive scholarship on the ‘cult of personality’ surrounding Hitler, few studies exist of ‘personality’ (Persönlichkeit) as a core concept in Nazism’s reorganisation of cultural discourses and practices at every level – and for our purposes most significantly, in film.13 Film-aesthetic writings of the 1930s, for instance, repeatedly centre on ‘personality’ as the quality that will in future distinguish German film art from Hollywood kitsch, indeed that will engineer a much desired aesthetic elevation of the film medium t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1. Film as Art: A Cinema of Personality

- 2. The Actor in the Cinema of Personality

- 3. The New Film Art: Exhibition

- 4. Personality and the Volkisch Sublime: Carl Froelich and Emil Jannings

- 5. Marlene Dietrich: From the Sublime to the Beautiful

- 6. Zarah Leander: From Beautiful Image to Voice Sublime

- 7. Leander as Sublime Object

- Bibliography

- Index

- List of Illustrations

- eCopyright