- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

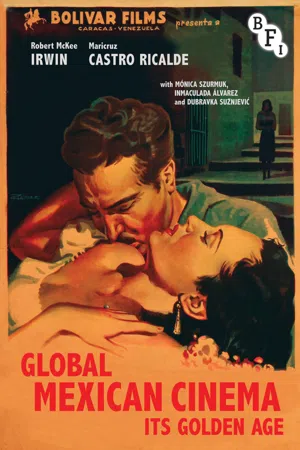

The golden age of Mexican cinema, which spanned the 1930s through to the 1950s, saw Mexico's film industry become one of

the most productive in the world, exercising a decisive influence on national culture and identity.

In the first major study of the global reception and impact of Mexican Golden Age cinema, this book captures the key aspects of its international success, from its role in forming a nostalgic cultural landscape for Mexican emigrants working in the United States, to its economic and cultural influence on Latin America, Spain and Yugoslavia. Challenging existing perceptions, the authors reveal how its film industry helped establish Mexico as a long standing centre of cultural influence for the Spanish-speaking world and beyond.

the most productive in the world, exercising a decisive influence on national culture and identity.

In the first major study of the global reception and impact of Mexican Golden Age cinema, this book captures the key aspects of its international success, from its role in forming a nostalgic cultural landscape for Mexican emigrants working in the United States, to its economic and cultural influence on Latin America, Spain and Yugoslavia. Challenging existing perceptions, the authors reveal how its film industry helped establish Mexico as a long standing centre of cultural influence for the Spanish-speaking world and beyond.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Global Mexican Cinema by Maricruz Ricalde,Robert McKee Irwin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Spanish Language. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Rumba Caliente Beats Foxtrot: Cinematic Cultural Exchanges Between Mexico and Cuba

Maricruz Castro Ricalde

AFFECTIONS AND REJECTIONS

This chapter explores multiple aspects of the cinematic links established between Mexico and Cuba during Mexican cinema’s golden age. These links brought the countries closer together, and even though Mexico’s industry was stronger and wielded greater influence in Cuba than vice versa, from the beginning to the end of its golden age, Mexican culture was not immune to the influence of the rhythms, songs, costumes, settings, behaviours and plots of a genre created by Mexican cinema based around the cluster of lovely Cuban women known as rumberas (rumba dancers) who began to arrive in Mexico, where they became mainstays of its cinema. Although some Cubans were not happy with the way in which these movies, whether filmed in Mexico or in Cuba, constructed Cuba through stereotypical notions of the island as a Caribbean paradise, others were grateful to see a Cuban presence magnified throughout Latin America that was only possible thanks to Mexican cinema’s intense interest in Cuban culture.

Some Cuban critics were vigilant, pointing out fictions, errors, falsifications, rejecting the many representations they saw as excessively primitive, lustful or exotic. But others, perhaps underestimating Mexican cinema’s reach, ‘remained silent, a common phenomenon throughout the golden age of Mexico’s cinema, considered mainly massive, popular, industrial and, therefore, disdained by the haughty Latin American intelligentsia’ (Verdugo Fuentes). While Cuban journals celebrated the international success its stars achieved through the Mexican industry, they lamented the way it portrayed Cuba, or simply wished its defects away by ignoring its existence.

The ranchera comedy is what initially established Mexican cinema’s foothold in the Cuban market with the astounding triumph of Allá en el Rancho Grande, although this genre fell quickly into disfavour, opening up opportunities for Argentine cinema to become the leading exporter of Spanish-language product to Cuba in the late 1930s. But the ranchera and other genres rooted in Mexican popular culture would again become the favourites of Cuban audiences even as most Cuban critics remained lukewarm. The success of the ranchera comedy and rumbera musical, a genre that became a huge hit in the late 40s, allowed Mexico to assume an unchallengeable leadership position among Spanish-language producers through the 50s, with Mexican product circulating in quantities three times greater than those of all other Spanish-language producers combined (Douglas, pp. 318–19). While the ranchera genre was understood to be essentially Mexican in content, the rumbera films were more ambivalent in their focus, with Mexican Gulf coast contexts blurring into Cuban ones, with Cuba’s Afro-Latin American roots ultimately coming to define its culture in opposition to that of mestizo Mexico. Cuban audiences identified with superficial elements essential to stereotypes of the Caribbean: music, landscapes, exuberance, colour that could be imagined (in the mostly black-and-white films) in the paradox of costumes that were baroque in their scantiness. Likewise, the phenomena of migration and industrialisation, experienced in these years through all of Latin America, allegorised in stories about innocent girls from the provinces trying to make it in rough, modern cities by dancing in cabarets, allowed recent arrivals to the city (whether Mexico City, Havana, Los Angeles or Bogotá) to find a cultural anchoring in the titillating cinematic representations of the rumbera genre.

Meanwhile, as Mexico became Latin American cinema’s mecca, its studios received a great number of Cuban artists and professionals, many of whom established permanent residency in Mexico City, including pioneers in the Mexican industry such as director Ramón Peón and actor Juan José Martínez Casado, and some of its biggest all-time stars, including rumberas María Antonieta Pons and Ninón Sevilla. However, there was also a moment in the latter half of the 1940s of a certain fluctuation in flows as the possibility arose that Cuba’s own film industry would gain momentum. During that period, Cuban expatriots and Mexicans alike travelled more often to Havana in hopes of participating in different media projects, very few of which came into fruition. Only those in the music business were able to return to Mexico with signed contracts, and by the mid-1950s Cubans were resigned to seeing their culture represented mostly through Mexican–Cuban co-productions whose content was usually determined by the Mexican industry’s need to export them widely – to audiences that wanted to see Cuba represented as a sensuous and exotic island paradise and that had little interest in other themes, including representations of major Latin American heroes and writers, such as José Martí, whose biopic, La rosa blanca (Emilio Fernández, 1954), was a box-office flop.

Reactions to Mexican cinema would turn ambivalent in these years as Cubans’ dreams of founding their own sustainable industry faded, and Mexican cinema began to lose its lustre as well, although it remained very popular in Cuba right up to the revolution of 1959. Throughout the 1950s, Cubans continued to travel to Mexico to learn the ropes of the business and perhaps meet eager investors or sign on to fruitful collaborations. Others complained: ‘it is time that Mexican cinema realised the enormous responsibility it has as an industry that exercises a huge influence on the multitudes’ (Bohemia, 21 March 1948, p. 86). Mexican cinema had indeed imposed its cinema not only as a product for Cuban moviegoers, but also as the best Spanish-language medium for Cuban performers including actors, dancers and musicians to work in, and the most frequent portrayer of Cuban culture on the silver screen.

This chapter lays out the complexity of the cinematic relations between Mexico and Cuba, marked as they nearly always were by contradictory attitudes oscillating between affection and rejection. As in the case of other countries, although audiences continued to express their own tastes, a segment of the press attempted to implant a vision of cinema as artistic expression. This vision would be realised following the revolution of 1959, after which the only Mexican films remaining in circulation were those exhibiting a social realism that privileged dramatic narrative structures differing significantly from the bulk of golden age cinema, which had built on traditions of musical revue or vaudeville-style theatre, especially in the cases of Cuban audiences’ favourite genres: the ranchera comedy and the rumbera musical.

MUSIC: A LANGUAGE WITHOUT BORDERS

While the rise of the tango was key for the appropriation of certain aspects of Argentine culture in Mexico and the rest of Latin America, from the first decade of the twentieth century, Cuban popular music made its own mark. The incorporation of rhythms dear to Cubans such as the son, the rumba and the habanero (antecedent of the popular danzón) into everyday life in Mexico City and Mexico’s cities most connected to Caribbean culture, such as Veracruz and Mérida, was reinforced thanks to the appreciation shown for Caribbean sounds by Mexican composers such as Juventino Rosas or Manuel María Ponce. Postrevolutionary Mexico saw its dancehalls come alive with danzόns and other Caribbean-influenced music, along with Argentine tangos, which began to take hold alongside more traditionally Mexican rhythms.

Of course, the seduction exercised by melodies from places like Argentina and Cuba was possible only when they were disseminated through international cultural industries (the recording industry, radio, film); when these cultural interactions did occur (as they did with Cuban, Mexican and Argentine music, but did not with, for example, Chilean, Venezuelan or Bolivian music), they promoted the national cultures they represented to the world while their reterritorialisations abroad, where foreign artists incorporated them into their repertoires, simultaneously made it ever more difficult to discern origins. Just as the cultural industries strengthened notions of national culture by nationalising once regionally identified musical genres, their transnational reach and the cultural exchanges they promoted diluted these marks of identity, favouring the incorporation of formerly ‘national’ genres throughout Latin America, and the promotion of what has been called a ‘transnational aural identity’ (D’Lugo, ‘Aural Identity’). Thus, ‘Cachita’ – put to music by the NewYork-based Puerto Rican Rafael Hernández and whose lyrics were written by Mexico-based Spaniard from Bilbao, Bernardo San Cristóbal – set a whole generation dancing following its 1936 broadcast on Mexico City’s XEB radio, sung by Yucatecan crooner Wello Rivas in a duet with Mexican Margarita Romero (Granados, p. 24).

Convergences of this sort, of artists from different locations, both in music and in film, began to transform Mexico’s capital into the Hollywood of Latin America that it would definitively be by the mid-1940s. Moreover, the unprecedented triumph of ‘Cachita’ is emblematic of the changes in taste occurring in the epoch in which, in effect, the foxtrot, a genre associated with metropolitan style (US big bands), was being cast aside for its ‘coldness’ and replaced by rhythms that had previously been rejected for their association with marginalised groups, spaces and symbolic realms. The arrabal (a term used for poor neighbourhoods in Argentina and Uruguay) and carpa (informal mobile theatre set up inside tents, once common in Latin America), with their caliente (hot) rhythms such as the rumba or the cha-cha-cha, were conquering audiences all over the world, a trend allegorised in song lyrics about their popularity among the French and other non-Latin Americans – ‘The Frenchman has fun like this/as does the German/and the Irishman has a ball/as does even the Muslim’ (‘Cachita’) – even as they filtered in the presence of a blackness – ‘and if you want to dance/look for your Cachita/and tell her “Come on negrita”/let’s dance’ – denied in the official discourse of those Spanish-speaking countries wielding the greatest economic power in the region: namely, Argentina and Mexico, the latter of which would eventually incorporate Afro-Latin American culture into its cinema – although being careful to mark it as Cuban and not Mexican.

The recording industry and the power exercised through its greatest channel of transmission, the radio, in the 1930s would be accompanied by cinema, which, with its incorporation of sound technology, would absorb for the Latin American market the most popular Cuban artists of the era, including Rita Montaner and the ensemble Caribe, as seen already in the early sound film La noche del pecado (Miguel Contreras Torres, 1933), or Juan Orol’s opera prima, Madre querida (1935), which featured the music of Cuban artist Bola de Nieve. Over the course of the years associated with Mexican cinema’s golden age, Cuba’s musical community would grow significantly in both number and influence, producing internationally acclaimed artists such as Kiko Mendive, Dámaso Pérez Prado, Benny Moré, Trío Matamoros, Celio González, Celia Cruz and Sonora Matancera, among many others. This music was incorporated into movies, and was further promoted in the popular artistic caravans that toured for months at a time through the small towns and big cities of Mexico and the rest of Latin America and the Caribbean. It is not easy to imagine a movie starring a Cuban rumbera such as María Antonieta Pons, Ninón Sevilla, Amalia Aguilar or Rosa Carmina without the intervention of one of the Cuban musicians mentioned above.

The exchanges between Cuba and Mexico not only involved Cuban musicians and singers coming to Mexico, whether on tour or to stay temporarily or permanently, but also led to the incorporation of Mexican popular songs and styles into the repertoires of Cuban artists. At the same time, Mexican recording composers and artists such as Agustín Lara, María Grever, Toña la Negra and Trío los Panchos made Caribbean genres such as the bolero Mexican.

While actors who happened to be talented singers, as was the case of tango chanteuse Libertad Lamarque in early Argentine sound cinema or ranchera composer and singer Lorenzo Barcelata in 1930s Mexican film, had played an important role in Latin American talkies from the beginning, with the rise of the international recording industry and the diffusion of the recordings of Latin American artists across the hemisphere, film-makers began to give significant screen time to musicians who were not experienced as actors, as was the case of ‘mambo king’ Dámaso Pérez Prado in Al son del mambo (Chano Urueta, 1950), a film in which the beloved Cuban singer and actress Rita Montaner also starred. Without playing a speaking role, but instead forming part of the musical groups that added so significantly to the atmosphere of many films, Kiko Mendive became a universally known face through his visual (and musical) presence in Juan Orol productions such as Balajú (Rolando Aguilar, 1944), La reina del trópico or Embrujo antillano (Geza Polaty, 1947), among many others, or in plots protagonised by other rumberas such as Rosa Carmina in Tania, la bella salvaje (Juan Orol, 1948) or Ninón Sevilla in Señora Tentación (José Díaz Morales, 1948).

Mexican films, such as Al son del mambo (1950), featured Cuban musicians and dancers

Although music was one of the main channels through which Cuban culture was able to reach other regions, it is important not to leave out the sizable contingent of Cuban actors that began appearing in Mexican cinema from the first years of sound production. For example, Juan José Martínez Casado played the memorable role of the Spanish bullfighter ‘El Jarameño’ in Mexico’s first major sound film, Santa, while René Cardona was one of the lead actors in the milestone 1936 film Allá en el Rancho Grande, and Enrique Herrera played Emperor Maximilian in the historical drama Juárez y Maximiliano (Miguel Contreras Torres, 1934). And over the years, the list grows much longer, with nearby Cuba being one of the foreign nations most present in the casts of Mexican golden age films. Marta Elba Fombellida, who had acted in the Cuban movie La que se murió de amor (Jean Angelo, 1942), upon moving to Mexico, began writing for the era’s most important film magazine, Cinema Reporter. She mentions numerous Cubans (born and/or raised on the island) who were working in Mexican film: Pituka de Foronda and her half brothers Rubén and Gustavo Rojo (born to Spanish parents), Carmen Montejo, María Antonieta Pons, Chela Castro, Blanquita Amaro, Lina Montes, among a half dozen others (16 September 1944, pp. 29–31). Other names that might be added to this list include: Issa Morante and the next generation of Cuban rumberas (Ninón Sevilla, Amalia Aguilar, Rosa Carmina, Mary Esquivel), along with Otto Sirgo and Dalia Íñiguez, to name only a few of the most successful. This list includes actors who established long-term, solid careers in Mexican film, and others whose presence was less memorable; this exodus illustrates where Cuban artists went to pursue a film career once that, in the words of Fombellida, ‘Mexico had become the place of Latin American cinematic assemblage’ (ibid., p. 30).

Cuban cinema prior to the revolution is little studied, as Cuba’s own golden age of cinema was born of the 1959 revolution and the foundation of the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (widely known as ICAIC). Earlier Cuban film production, to the extent that it has been studied at all, has been largely disdained by critics for its adherence to popular styles of the era and its lack of originality, as well as its lack of adequate production financing and the resulting aesthetically and technically inferior quality of its product. Co-productions have likewise generally been ignored as not authentically national, despite the fact that such films as Más fuerte que el amor (Tulio Demicheli, 1955) and Mulata were launched with fanfare and became big box-office earners as vehicles for some of the biggest stars of the epoch: Jorge Mistral and Miroslava, and Ninón Sevilla and Pedro Armendáriz, respectively. And even though Mexican studios produced megahits using scripts based on Cuban radio soap operas, the emblematic case being El derecho de nacer (Zacarías Gómez Urquiza, 1952), these too have been little studied. There are numerous possible reasons for the oversight on the part of Cuban critics: for example, the feeling that Mexican investors only used the island’s resources and talent without leaving behind anything worthwhile; or the conviction that these films’ representations of Cuba’s history a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1: Rumba Caliente Beats Foxtrot: Cinematic Cultural Exchanges Between Mexico and Cuba

- 2: Así se quiere en Antioquia: Mexican Golden Age Cinema in Colombia

- 3: Mexico’s Appropriation of the Latin American Visual Imaginary: Rómulo Gallegos in Mexico

- 4: Latin American Rivalry: Libertad Lamarque in Mexican Golden Age Cinema

- 5: Mexican National Cinema in the USA: Good Neighbours and Transnational Mexican Audiences

- 6: Panhispanic Romances in Times of Rupture: Spanish–Mexican Cinema

- 7: ‘Vedro Nebo’ in Far-off Lands: Mexican Golden Age Cinema’s Unexpected Triumph in Tito’s Yugoslavia

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

- List of illustrations

- eCopyright