![]()

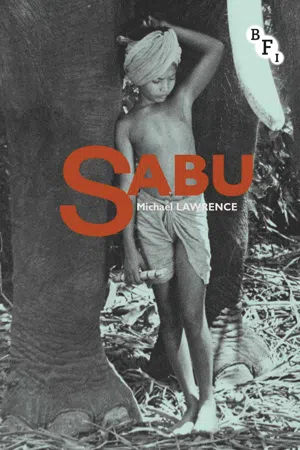

1: ‘Starring’ Sabu

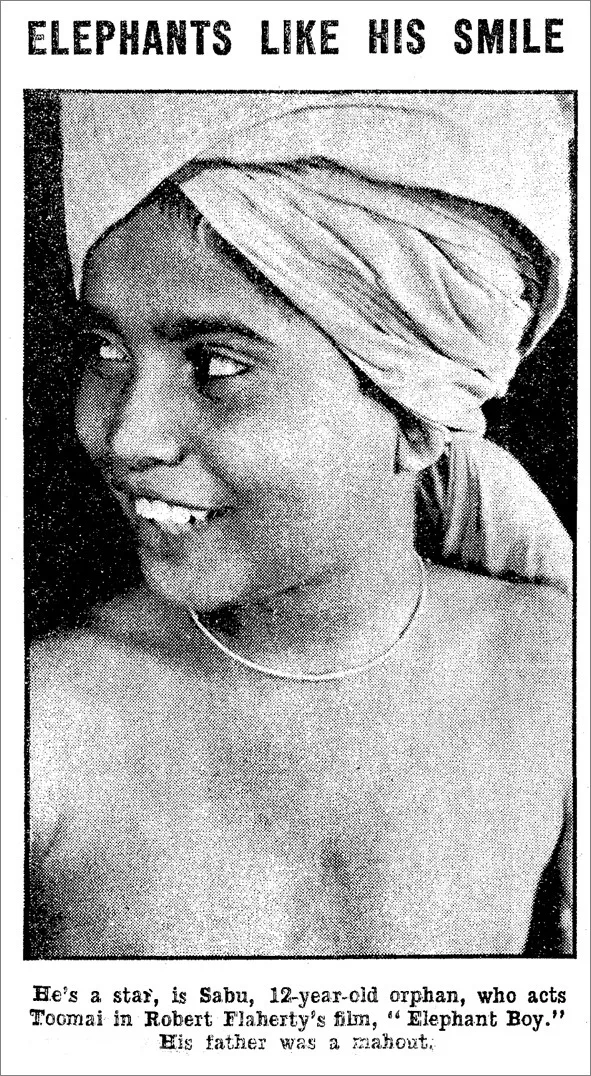

When Elephant Boy was shown in cinemas during the spring of 1937, audiences around the world were finally and as it were formally introduced to the young Indian boy by the name of Sabu. Elephant Boy is perhaps the definitive Sabu film, and the star would be known as the ‘elephant boy’ for the duration of his career. The dominant contours of his persona were arguably crystallised by the promotion and publicity surrounding this film, and his debut screen performance would epitomise his unique attractions for a generation of fans. Contemporary reviews of Sabu’s performance in Elephant Boy, and the features that appeared in the press before and following the film’s release, inaugurated and established the vocabulary that would be repeatedly deployed to describe his body, to define his labour, to explain his appeal and to account for his success. By the time the film was released, numerous photographs of Sabu had featured in newspaper accounts of the film. The story of his ‘discovery’ had been told and retold many times, and it was widely reported how Sabu’s participation in the production of Elephant Boy had totally transformed his life. The wonderful ‘rags-to-riches’ tale was repeated over and over again: until very recently he was a poor and pitiful orphan, roaming the jungles of southern India, but now, at the age of thirteen, he was a film star, working for one of the most important men in the British film industry.

Sabu’s enduring identification with Elephant Boy was thoroughly constitutive of his star image and had a determining impact on his film career as an adult. Sabu was always associated with elephants, and with the animal kingdom more generally – with, in other words, the non-human – and also with youthfulness and boyishness – with, in other words, the non-adult. Consequently, the manufacture or construction of Sabu’s star persona was in certain and important respects continuous with traditional ideological representations of colonised subjects, even though, or perhaps precisely because his rise to stardom coincided with the decline and eventual dismantling of Britain’s imperial power in India. As the historian J. M. Blaut has argued, ‘the coloniser’s model of the world’ viewed non-Europeans as ‘undeveloped … more or less childlike’.10 According to this ‘model’, these ‘childlike’ subjects ‘could of course be brought to adulthood, to rationality, to modernity, through a set of learning experiences, mainly colonial’.11 Popular accounts and representations of Sabu’s early years in India and of his being brought to England at the age of twelve to become a film star invariably reflected the attitudes and assumptions associated with the colonialist model Blaut describes.12

Back in the winter of 1936, before Elephant Boy had been released, the Times of India reported that Sabu had ‘become the hero of Britain’s biggest film studio, and [was] one of the highest-paid actors in London’.13 The newspaper explained that

Sabu and his smile have become familiar to the British public both by their intrinsic charm and through a campaign of adroit press publicity. […] His picture appears more frequently in the … press than that of any other Indian and his personality is played up for all it is worth.14

The popularity of Sabu is here described as rooted in an innate appeal but also as the result of the deliberate manufacturing of his public image. The hoopla accompanying Elephant Boy’s release indeed revolved almost entirely around the vitality of the young star. Sabu’s ‘intrinsic charm’ was emphasised from the start so as to differentiate him from the more obviously manufactured child stars of the period (such as Shirley Temple). The New York Times described Sabu as ‘a sunny-faced, manly little youngster, whose naturalness beneath the camera’s scrutiny should bring blushes to the faces of the precocious wonder-children of Hollywood’.15 An image of Sabu – as small but strong, with an infectiously delightful smile, and an engagingly insouciant and marvellously confident screen presence – was established at the very beginning of his career, and this image remained affixed to the actor until his death in 1963. The palpable enthusiasm and energy that critics discerned in Sabu’s portrayal of the mischievous and intrepid hero of Elephant Boy were to become the defining features of his screen persona, and his debut performance thus became a touchstone for the popular reception of his subsequent film roles. A sustained focus on Sabu’s performances, beginning with Elephant Boy, in conjunction with an analysis of the construction of his public persona, will here provide the means with which to re-evaluate his significance as an icon. Attending to both the material conditions and the expressive creativity of his labouring as an actor will enable a reconsideration of his agency and autonomy as an ‘exotic’ star working for industries whose products invariably reflected the ‘coloniser’s model of the world’.

An early newspaper item about Sabu

Elephant Boy is an adaptation of ‘Toomai of the Elephants,’ a tale from The Jungle Book (1894) by Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936). According to Wallace W. Robson, the most important literary source for Kipling’s stories was ‘undoubtedly the anecdotes of Rudyard’s father, Lockwood Kipling, in his Beast and Man in India (1891)’.16 Lockwood Kipling had devoted a chapter of his book to the elephant, which he described as ‘one of the wonders of the world, amazing in his aspect and full of delightful and surprising qualities’.17 In The Jungle Book, Toomai is the son of a mahout (elephant driver); the story concerns the boy’s adventures with his elephant, Kala Nag, and chiefly his participation in an elephant drive organised by Colonel Petersen, a representative of the British government. Much of the material in Beast and Man in India concerning elephants was drawn from an earlier book, George Sanderson’s Thirteen Years among the Wild Beasts of India (1879); while working for the British Government in India in the 1860s, Sanderson had introduced the use of the stockade (or keddah) for capturing wild elephants, and he is assumed to be the model for Rudyard Kipling’s Colonel Petersen.18 In Beast and Man in India it is claimed that mahouts ‘tell and believe of the beasts in their charge more wonderful stories of intelligence than any in our children’s books’, and ‘Toomai of the Elephants’ draws on one particular legend, suggested by trampled areas discovered in the jungles – that herds of wild elephants often gather together at night to dance. Lockwood Kipling writes, somewhat indulgently:

Let us believe, then, until some dismal authority forbids us, that the elephant beau monde meets by the bright Indian moonlight in the ballrooms they clear in the depths of the forest, and dance mammoth quadrilles and reels to the sighing of the wind through the trees.19

Throughout Elephant Boy its young star displays both a bold confidence and an impish nonchalance whenever he is interacting with elephants, whether he is clambering nimbly up Kala Nag’s proffered leg, riding the elephant perched astride its head or lying face down its back, or expertly washing him in a river, balancing precariously on the elephant’s back as it slowly rolls over onto its side, and then vigorously scrubbing its ears with a rock. Several times in the film Kala Nag wraps his trunk securely around Sabu’s body and hoists the boy up onto his head, and numerous international posters for Elephant Boy depicted Sabu as Toomai suspended in space, gripped by the trunk of his beloved elephant companion. Reports of the discovery of Sabu that appeared in the press always emphasised that the child was a ‘bona fide elephant boy’, a ‘real-life Toomai’, and routinely claimed that there were extraordinary and even uncanny parallels between Kipling’s fictional boy hero and the real child who played him in the film; this was said to account for the boy’s incredible ease with his elephant co-stars. In much of the publicity for Elephant Boy it is often difficult to tell where one boy – Sabu – ended and the other boy – Toomai – began. For example, in Sabu of the Elephants, a biography of the young star published in 1938, Jack Whittingham plagiarises Kipling to evoke Sabu’s formative years in the jungles. Kipling describes how Toomai liked ‘the rush of the frightened pig and peacock under Kala Nag’s feet; the blinding warm rains, when all the hills and valleys smoke; the beautiful misty mornings when nobody knew where they would camp that night’.20 In the biography, we read how Sabu

knew the rush of the frightened pig, the weird peacock calls, the sting of the blinding monsoon rains, and the smoke that came up from the hills and valleys when the rains ceased. He knew the thrilling misty mornings, the elephant drives, and the pounding of their great wild limbs against the timbers of the stockade.21

The early life of a real child (Sabu) is here described by simply duplicating language used by Kipling to evoke the fictional child Toomai in his original and fantastic tale. Due to his having been an authentic elephant boy, however, it is imperative that Sabu be distinguished from Toomai if his performance in Elephant Boy is to be properly recognised as a performance, and if his work in the film, his working for the film, is to be understood as his playing a character rather than his simply being himself.

The film which was to become Elephant Boy was originally conceived by Robert Flaherty, the American director often regarded as the ‘father’ of documentary film. Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (1922) had established for critics the non-fiction film as a distinct mode of cinema, and also inaugurated the director’s reputation as an adventurous chronicler of ‘obscure’ or ‘primitive’ peoples; the critic Siegfried Kracauer described Flaherty as ‘the rhapsodist of backward areas’.22 At the beginning of Elephant Dance, an epistolary account of the making of Elephant Boy published to coincide with the film’s release, the director’s wife and collaborator Frances describes their original ambition to present ‘the adventures of a little Indian boy on a big Indian elephant in the jungles of India with all the jungle creatures’, and then, by way of introducing the patron of this venture, asks:

But who could be found to produce such a film – a film that depended on a ‘star’ who was a mere boy, and a native boy at that, a quite ideal boy, moreover, who had yet to be discovered by some one of us somewhere in India! This needed a producer, it must be admitted, of no little courage and enterprise. Fortunately there was such a one in London. There was Alexander Korda.23

The Hungarian émigré Alexander Korda was, at the time, popularly considered the saviour of the British film industry. The Private Life of Henry VIII, which he had directed in 1933, was the first British production to receive the American Academy Award nomination for Best Picture, and it was hoped Korda would herald a new era in British cinema, with films oriented toward and attracting international audiences and thus competing more effectively with Hollywood. Korda had established London Films in 1932 and, in 1936, with financial support from the Prudential Assurance Company, opened the Denham Film Studios in Buckinghamshire, at that time the largest such facilities in Europe. H...