- 319 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

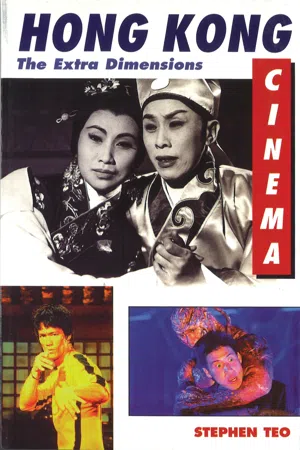

About this book

This is the first full-length English-language study of one of the world's most exciting and innovative cinemas. Covering a period from 1909 to 'the end of Hong Kong cinema' in the present day, this book features information about the films, the studios, the personalities and the contexts that have shaped a cinema famous for its energy and style. It includes studies of the films of King Hu, Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan, as well as those of John Woo and the directors of the various 'New Waves'. Stephen Teo explores this cinema from both Western and Chinese perspectives and encompasses genres ranging from melodrama to martial arts, 'kung fu', fantasy and horror movies, as well as the international art-house successes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hong Kong Cinema by Stephen Teo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Northerners and Southerners

Chapter One

Early Hong Kong Cinema: The Shanghai Hangover

THE BEGINNING

The development of cinema in Hong Kong cannot be dissociated from the development of cinema in the Chinese Mainland. Hong Kong was one of the birthplaces of Chinese cinema.1 It produced in 1909 the earliest two-reeler comedies: Right a Wrong with Earthenware Dish/ Wa Pen Shen Yuan and Stealing the Roasted Duck/ Tou Shao Ya, both adapted from the repertoire of Chinese operas. The director was a Chinese theatre actor-director and amateur film enthusiast named Liang Shaobo, but his producer was an American national, one Benjamin Brodsky, who had established the Asia Film Company in Shanghai.2 Brodsky had his eyes on the Mainland Chinese market when he started making his films in Hong Kong, thus setting in motion the first linkages between Hong Kong and Shanghai, two cities developing nascent film industries.

In 1913, Li Minwei, a theatre director, made Zhuangzi Tests His Wife/ Zhuangzi Shi Qi, an adaptation of a Cantonese opera (Li himself had to play the part of the wife because of a taboo against women appearing in the theatre). Li had founded a dramatic troupe, the Ching Ping Ngok, with Liang Shaobo. Together with Liang Shaobo, his brother Li Beihai and cousin Li Haishan, Li established the Minxin Company (or the China Sun Motion Picture Company) in Hong Kong in 1923, thus initiating the rudiments of a film industry in the territory. However, in 1924, the Minxin Company had re-located to Guangzhou after its application to rent land to build a studio was rejected by the Hong Kong government. They produced a feature film, Lipstick/ Yanzhi, which was released in Hong Kong's New World Theatre in 1925. That year, a general strike was called in Hong Kong and Guangzhou. The company was greatly affected by the strike (all film activity including the production and exhibition of films came to a stop) and Minxin once again re-located in 1926, this time to Shanghai. The company was incorporated into the Lianhua Film Company (known in English as United Photoplay Services) in 1930.

Li Minwei was an avid documentarist and photographer. He is better known today for his archival footage of Dr Sun Yat-sen, the founder of the Nationalist Party (the Kuomintang, henceforth abbreviated as KMT) and leader of the Chinese Revolution of 1911 which toppled the Qing Dynasty and put China in the direction of its republican destiny. In the 1920s, Sun was still leading the revolution: his mission was to unify the country under the principle of tianxia weigong, translated by KMT party stalwarts as 'the goal of great commonwealth'. Li Minwei followed Dr Sun as he went about achieving this goal and, between 1926–8, photographed the statesman in his last efforts to consolidate the revolution through the 'Northern Expedition' – an attempt to rid northern China of its warlords and unify the country under KMT rule. However, Sun died and it was left to his successor, Chiang Kai-shek, to lead the Northern Expedition.

Li Minwei's documentary footage of Dr Sun Yat-sen, Chiang Kai-shek and other KMT leaders has survived as the standard photographic records of the historic personalities of early republican China. This footage may be seen in A Page of History/ Xunye Qianqiu, an edited version of the original material shot by Li and passed down to his descendants. Li's backing for Sun's republican philosophy and political aims is the first instance in Chinese film history of a film-maker using the new medium of film to propagate a political cause. It was Li who raised the slogan 'Save the Nation Through Cinema!'. As a producer, Li also supervised the production of fictional feature films, significant precursors of the film industry that would develop: his 1927 version of Romance of the West Chamber/ Xi Xiang Ji (known in export versions as Way Down West), was an outstanding example of a fantasy martial arts genre movie in the silent era. Made in Shanghai, it foreshadows the films of King Hu and Tsui Hark, showing that the early Shanghai cinema is the legitimate precursor of the modern Hong Kong film industry.

When the Minxin company became a part of the Lianhua company in 1930, Li personally supervised the production of the company's initial projects: Spring Dream in the Old Capital/ Gudu Chunmeng (1930), Wild Grass/ Yecao Xianhua (1930) and Love and Duty/ Lian'ai yu Yiwu (1931). These silent classics shared the common theme of love in a feudal setting and all three featured Ruan Lingyu (dubbed China's Garbo) in the best parts of her career.3 The trilogy secured Lianhua's reputation as the most prestigious and important studio in Shanghai.

The force behind Lianhua was Luo Mingyou, a Hong Kong-born, Peking-educated theatre manager turned producer. He established the North China Film Company in 1927 and controlled the distribution circuit and theatre business in five northern provinces. Luo had brought together investors from Peking, Shanghai and Hong Kong to start the Lianhua company. Luo and Li merged their companies with a third company, the Da Zhonghua Bai He Film Company, and took in another partner, the printing magnate Huang Yicuo.4 The head office was initially in Hong Kong and the company's largest investor was reported to be the local tycoon Sir Robert Ho Tung, who was named the managing director. The head office was re-located to Shanghai in 1931. By then, it was clear that China's biggest metropolis was proving to be a greater magnet for film talent than Hong Kong. However, the company maintained a branch studio in the colony even as Shanghai became the Mecca of Chinese film-making, initiating the golden age of Chinese cinema in the 30s, with Lianhua playing a major role.

The golden age lasted several years, coming to a premature close when China became embroiled in war from 1937 onwards: first in the anti-Japanese war, then, after the defeat of Japan, in the civil war between the Nationalists and Communists which lasted until 1944. During the war period, Chinese film production continued in various cities, not least in Shanghai itself. After the fall of Shanghai on 13 August 1937, the Japanese occupied all sections of the city except the foreign concessions which were seized only in December 1941 after Japan's declaration of war on the Western powers. With the first stage of Japanese occupation in 1937, many of Shanghai's film talents dispersed to Hong Kong and other Chinese cities, but some remained behind in what became known as the 'Orphan Island': the foreign concessions still free of Japanese control. There, Shanghai's filmmakers continued their activities as before but with the Japanese keeping a watchful eye on them.

With the city's total capitulation in 1941, what remained of Chinese film-making in Shanghai came under Japanese control. The Japanese had built their own film-making facilities in Manchuria and Peking and soon took over production facilities in Shanghai as well. In 1942, they set up a coalition of all film companies under a 'United China' rubric that later came to be known as 'Huaying', the abbreviated form of the Chinese name for the United China Motion Picture Company Limited (or Zhonghua Dianying Lianhe Gufen Youxian Gongsi). Chinese historians and critics under the communist regime have long considered Huaying a 'sham' Chinese company and looked with disfavour on all those who worked for it. The Shanghai film industry under the Japanese has remained a historical 'black hole', the issue being sensitised by post-war political recriminations against those film-makers who had stayed behind to work in Huaying and who were consequently regarded as collaborators or traitors. Further light can only be shed on this period by research undertaken under more favourable political conditions.5

As China dug in to fight a war with Japan, film-makers on the Mainland were forced to make films on the move – in Wuhan, Chongqing, Hong Kong. A new genre appeared in Chinese cinema: the 'national defence' movie. These were patriotic war films that recreated images of the Japanese overrunning Chinese villages, committing atrocities, and the heroic resistance of the Chinese against the foreign invaders. National defence movies were made not least in Hong Kong where many film-makers from Shanghai had fled after the Japanese occupied the Chinese sections of the city in 1937.

The history of Hong Kong cinema in the pre-Pacific war period is at best a sketchy one because of the almost total lack of extant films. From the sources available, we know that a quite advanced film industry had developed in the colony by the early 30s as the territory recovered from the crippling effects of the general strike which began in June 1925 and lasted until October 1926 (the film industry took until 1929 to resume normal production of films). Among the leading production companies were the Hong Kong branch of the Lianhua studio, managed by Li Beihai, which employed directors Liang Shaobo and the Chinese American Kwan Manching, who had returned to Hong Kong and China armed with experience in Hollywood. Kwan was also one of the supervisors of the 'Overseas Lianhua' branch based in America where, in 1933, he and a fellow Chinese American Chiu Shu-sun (also known under his Americanised name of 'Joseph Sunn') founded the Grandview (Daguan) Company. It was Grandview which produced, in America, one of the earliest Cantonese talking pictures, The Singing Lovers/ Gelü Qingchao in 1934 (the first Cantonese talkie was White Gold Dragon/Baijin Long, produced in 1933 in Shanghai by the Tianyi Company). The next year, Grandview was established in Hong Kong where it became one of the best-resourced studios in the territory, joining the ranks of the major film companies Universal, Nanyue and Tianyi, all established in Hong Kong a year earlier.

Tianyi was perhaps the best known of Grandview's competitors. Originally based in Shanghai, the studio had made its name through its prolific production of escapist martial arts fantasies popular throughout China. However, such films were considered morally decadent in conservative circles (they were certainly not all that well regarded by leftist progressives either) and the government moved to ban them. In 1933, Tianyi had a great success with White Gold Dragon, the first Cantonese talking picture ever made, which was so successful in the Cantonese-speaking regions of southern China that studio boss Shao Zuiweng thought it opportune to move his studio away from Shanghai and closer to the Cantonese world where he could continue to produce his 'morally decadent' pictures in Cantonese to meet the growing demand. He moved to Hong Kong. It not only saved the studio's fortunes but pointed the way for the territory to become a viable centre of movie production. At the same time, it ushered in the era of sound movies. Tianyi, and companies such as the China Sound and Silent Film Production Company (founded by the tireless Li Beihai), led the way in the production of local sound movies which first appeared in Hong Kong in 1933.6

The use of Cantonese was to spark a contentious debate among nationalists and aroused the opposition of Mandarin-language purists. In 1936, the KMT government in Nanjing passed an edict banning Cantonese movies. This was appealed against by Cantonese film-makers in Hong Kong and Guangzhou.7 Due to the outbreak of war with Japan in 1937, the government, with more pressing matters on its hands, conveniently closed its eyes to the edict. Cantonese movie producers in Guangzhou, the ones most affected by the edict (Guangzhou had developed into a major centre of Cantonese movie production in the mid-30s) simply moved down to the British-controlled colony, and Hong Kong emerged as the base for Cantonese movies with a sizeable overseas market in Southeast Asia and America. In this way, Hong Kong's film industry counted on the use of Cantonese dialect as a selling point. In 1935–7, it is estimated that a total of 157 Cantonese films were produced in the territory. Before 1935, an average of only four Cantonese films had been produced per year since the arrival of sound.8

Of the production companies making Cantonese movies in Hong Kong, Grandview occupied the largest studio space and employed some of the most prestigious film-makers, including its founders Chiu Shu-sun and Kwan Man-ching, both directors in their own right. They established reputations as major directors of Cantonese films and exerted an impact on future Cantonese film-makers such as Lee Sun-fung, Ng Cho-fan, Ng Wui and Lee Tit, who were all given their first big breaks as fledgeling talents by Grandview. However, practically none of the early films produced by the company has survived, including the award-winning 'national defence movie' Lifeline/ Shengming Xian (1935), directed by Kwan Man-ching. Chiu, who supervised all of Grandview's productions, himself directed the well-regarded national defence movies Hand-to-Hand Combat/Rou Bo and 48 Hours/ Sishiba Xiaoshi in 1937, the year when full-scale war broke out between China and Japan.

The anti-Japanese war stimulated Hong Kong's film industry as filmmakers rushed to put out national defence movies. As the mainstream film industries in China fell under the control of the Japanese, Hong Kong was the only place where patriotic national defence movies could be made freely (even though the Japanese exerted pressure on the British authorities to ban or censor them). Historians have usually pointed to the outbreak of war on the Mainland as a turning point in Hong Kong's film history. It led to the growth of the local film industry as Hong Kong absorbed migrants fleeing Shanghai. In fact, the migration flow had started earlier, and the historical intercourse between Hong Kong and Shanghai went much deeper than is suggested by the consequence of migration due to the cataclysm of war (although political uncertainties caused by the incursions of the Japanese army into China from 1931 onwards would have played their part).

The re-location of the Tianyi studio in 1933–4, triggered by domestic political factors (the threat of a ban on the martial arts fantasies and tales of superstition that were the staple products of the studio), was an event of perhaps greater significance than the migration of directors during wartime Shanghai. Tianyi's move to Hong Kong would see the Shaw Brothers (including Runde, Runme and Run Run) expanding and establishing an empire in Southeast Asia which they oversaw from their headquarters in Hong Kong. The original Tianyi Company evolved into several companies, each more famous than its predecessor. In 1936, a fire destroyed the Tianyi studio and out of its ashes grew the Nanyang Company, managed by Runde Shaw (Shao Cunren) who was recalled from Singapore by elder brother Shao Zuiweng. Runde later re-organised his company into Shaw and Sons. In 1956, Run Run Shaw (Shao Yifu) established the Shaw Brothers studio, the most famous of the various film-making enterprises of the Shaw Brothers.

Thus, Tianyi's move to Hong Kong (as well as the cross-Pacific move of the Grandview Company) was a prescient one, signalling Hong Kong's vast potential as a production and distribution base from which a company like Tianyi (and its subsequent clones) could export their Shanghai-produced Mandarin films and Hong Kong-produced Cantonese films to Southeast Asia and other key markets with large Chinese communities. Directly or indirectly, the Shaws brought along other members of the Shanghai film-making fraternity. The Nanyue Company was founded by Zhu Qingxian, a pioneer of sound recording in the Shanghai film industry who had invented his own recording apparatus for talking pictures. Directors and scriptwriters who had associated with the Tianyi Company in Shanghai also made the move to Hong Kong. They included Su Yi (who ran the Universal Company), Tang Xiaodan, Wen Yimin and Hou Yao. These film-makers were well entrenched in Hong Kong by 1937 when members of the 'progressive' movement in Shanghai cinema started pouring into Hong Kong to continue their struggle: the burning issue of the day being the anti-Japanese war and the need to propagate the war effort of the Chinese people.

THE IMPERATIVES OF WAR

When the Japanese army overwhelmed Shanghai in 1937, Hong Kong was virtually used as a rearguard station for Shanghai-based film-makers until it too came under the yoke of the Japanese in December 1941. Probably the most prominent director to make the southward migration was Cai Chusheng, a Cantonese born in Shanghai. The latter became the first Chinese film-maker ever to win a prize in an international film festival, in Moscow in 1935, for his Song of the Fishermen/Yuguang Qu. One of Cai's briefs as an émigré director of the patriotic left was to make anti-Japanese propaganda films from Hong Kong. He complied with films...

Table of contents

- Cover page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Part One: Northerners and Southerners

- Part Two: Martial Artists

- Part Three: Path Breakers

- Part Four: Characters on the Edge

- Bio-filmographies

- Index

- eCopyright