- 344 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

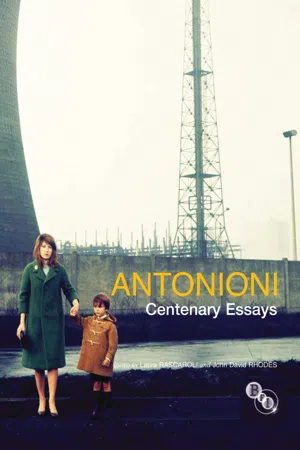

This collection of new essays by leading film scholarsaddresses Michelangelo Antonionias apre-eminent figure in European art cinema, explores his continuing influence and legacy, and engages with his ability to both interpret and shape ideas of modernity and modern cinema.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Jacopo Benci

IDENTIFICATION OF A CITY: Antonioni and Rome, 1940–621

A Possible Biography

Leave me alone, let me spend my life drop by drop, in this silence that is really my style … So if silence is my religion, let me be this way. And do not talk about me. Michelangelo Antonioni2

In the preface to his recent case study on L’avventura (1960), Federico Vitella pointed out the partial unreliability of published biographical information on Antonioni, ‘often undermined by a deliberate sidetracking put in place by the director himself, reluctant to spread “sensitive” information about his creative process’.3 The title of Renzo Renzi’s 1992 book, Antonioni, una biografia impossibile (Antonioni, An Impossible Biography), referred to Antonioni’s reticence in providing details about his life. In her discussion of Antonioni’s 1955 film Le amiche, Anna Maria Torriglia stressed the relevance of a past never fully disclosed or explained yet continuing to haunt the present. For Antonioni,

the present is just an enigma that can be solved only by exploring the past. It is not possible to know or make sense of an action in the present if we do not understand what lies behind it and do not launch ourselves into an inquiry – a true ‘journey’ – into the past.4

The aim of this essay is twofold: first, to trace the personal and intellectual journey that brought Antonioni from his native Ferrara to Rome in 1940; second, to examine how, over the following decades, he formed the image of Rome to be found in his films from N. U. (1948) onwards.

The study of a wide range of sources, including some previously overlooked ones, affords a more thorough picture of the intellectual milieu within which Antonioni built his visual and cultural framework, as well as a better understanding of the motivations informing the choice of locations for his films.

Ferrara, 1912–39

Michelangelo Antonioni was born in Ferrara on 29 September 1912, the second son of ‘self-taught middle-class’ parents.5 His father was a staunch fascist; yet, Antonioni said in 1967, ‘at the time of the March on Rome, as he did not want to participate, he was seized and beaten savagely’.6 The teenage Michelangelo attended ginnasio, preparatory school for classical studies, but completed his secondary studies at a technical institute.7 As an avanguardista, he adhered ‘in a sentimental and confused way’ – he recollected in 1978 – to fascism and its rituals; ‘some of their acts reminded me of Bandiere all’Altare della Patria by Balla, as some of their rallies reminded me of Boccioni’s Retata. But later, I had such a reaction to that ideology that everything was wiped out.’8

Antonioni enrolled at the Faculty of Economics and Commerce of the University of Bologna, where he graduated on 12 July 1938.9 In interviews, he talked about the lack of cultural stimuli in Ferrara in the 1930s, and claimed he owed his literary education to his friends Lanfranco Caretti, later a renowned philologist, and the writer Giorgio Bassani, both of whom studied literature in Bologna10 and distinguished themselves in the Littoriali della Cultura e dell’Arte, yearly cultural contests among students of Italian universities, held between 1935 and 1940 under the aegis and control of the Fascist Party.11 In 1985 Antonioni said,

[Ferrara] is a city with an important artistic tradition. In the twentieth century painters such as De Pisis, De Chirico (a good part of his metaphysical painting was created in Ferrara), futurists such as Funi and Depero lived for some time in Ferrara. Strangely, this historical and cultural ferment disappeared during Fascism, and there was almost nothing left of it. There were only three or four of us – Giorgio Bassani, Lanfranco Caretti and I – to form a sort of literary coterie.12

Such claims may be read to downplay the influence on the young Antonioni of the cultural ambience of Ferrara and its determining political and social factors.

By 28 March 1935 he had begun writing for the Ferrara newspaper, Corriere Padano, to which he regularly contributed film reviews, articles and stories for over five years.13 The paper’s founder, the fascist leader Italo Balbo – one of the four main planners of the March on Rome with which Mussolini came to power – was its chief editor for a brief period in 1925, after which he entrusted it to his close collaborator and friend, the journalist Nello Quilici.14 Balbo, Quilici and the Jewish lawyer Renzo Ravenna, the city’s podestà (mayor) from 1926 to 1938, set the political and cultural climate of Ferrara during Antonioni’s formative years.

As chief editor of Corriere Padano, as well as writer, cultural organiser and patron of the arts, Nello Quilici had links with intellectuals such as Papini, Soffici, Pirandello, Casella, artists like Achille Funi, the futurist ‘aeropittore’ Tato, De Pisis, Campigli, Martini and prominent fascist personalities such as Dino Grandi and Giuseppe Bottai.15 In the mid-1930s the cultural page of Corriere Padano allowed – as Lanfranco Caretti remarked – ‘for an unusual freedom, at least in the literary field, and made it possibile for us to discuss the writers whom we deemed significant’, such as Eliot, Joyce, Kafka, Mann, Proust, Valéry.16 In 1941, Antonioni would write about Quilici with admiration and fondness:

One did not understand how a man could read so much, yet on whatever publication – political, historical, economic, artistic, literary – one questioned him, he was aware, he knew it, he criticized it … [T]he sympathy he extended to me, was a source of pride for me.17

Antonioni’s favourite writers in the 1930s included Conrad, Gide, the Russians (‘there was always a Russian novel on my desk’), Kafka, Montale and Svevo, though he ‘felt closer to Penna and Campana and Pavese’. He also ‘read film books like crazy, Canudo to Spottishwoode [sic], Chiarini and Arnheim to Barbaro, Balázs to Vertov’.18

During his university years, Antonioni developed an interest in theatre, taking part in student companies as an actor, playwright, art director; for a time, he directed the theatre company of the GUF (Fascist University Group) in Ferrara.19 He obtained a distinction in film criticism and scriptwriting at the 1936 Littoriali in Venice, and participated in the 1937 Littoriali in Naples. In 1938 he was a fiduciary of the Ferrara CineGUF.20 Besides his intellectual exploits, he was a regular at Ferrara’s Tennis Club Marfisa, and his excellence as a tennis player helped him to improve his social status: ‘I was surrounded by the Ferrara aristocracy and by its rich bourgeoisie that came from an aristocratic rural background.’21

After graduation, while continuing to direct the GUF theatre, Antonioni took up a job at the Ferrara Chamber of Commerce,22 but was eager to break out of the boundaries of a provincial city like Ferrara. In the spring of 1939 he started contributing to the Rome-based fortnightly journal Cinema, founded in 1936 and directed from October 1938 to July 1943 by Benito Mussolini’s son, Vittorio. The editorial board of Cinema included Rudolf Arnheim (who left Italy in 1939 because of the racial laws), Francesco Pasinetti, Gianni Puccini and, later, Giuseppe De Santis, Mario Alicata, Pietro Ingrao, Carlo Lizzani. Though directed by Vittorio Mussolini, Cinema – as Vito Zagarrio has pointed out – ‘ended up putting together an anti-fascist editorial staff, and fostering, indeed, through the instrument of culture, a progressive political stance’.23

Antonioni’s first piece for Cinema was a four-page illustrated article, entitled ‘Per un film sul fiume Po’ (‘For a Film on the River Po’) and published in the 25 April 1939 issue. The director and film historian Carlo Lizzani, who was a contributor to Cinema from 1942 onwards, has provided a possible explanation of why the editors of Cinema published such a long article by a young and hardly known journalist from a northern provincial town:

The most important factor we shared then was the idea to get out of the film studios, and discover Italy in its various aspects, from north to south, which we did not know at all. In fact, we Romans looked with curiosity to those who (like Antonioni) came from the north. I remember that at that time we liked those images, those photographs of the Po that he brought to Cinema, they impressed us and gave us the idea that he was bringing a contribution to the knowledge of an Italy that was not known, just as we did not know Ciociaria, or Piedmont.24

Over three years before shooting his first cinematic work, Gente del Po (People of the Po, 1942–47), Antonioni sets out the reasons for choosing the river as a subject, and raises questions about the form (documentary or fiction) and approach this film should take. The relationship between the landscape and its inhabitants is defined in the article in terms of Stimmung or atmosphere: ‘People of the Po feel the river. We do not know in what way this feeling is made concrete, but we know that it is widespread in the air and that it is experienced as a subtle charm.’25

Ferrara to Rome, 1939–40

Determined to move to Rome, Antonioni turned to Nello Quilici for advice and help.26 In the summer of 1939, in Venice, Quilici introduced and recommended Antonioni to Vittorio Cini.27 One of Italy’s most prominent entrepreneurs, a friend and fellow citizen of Italo Balbo’s, Cini was the High Commissioner of the Universal Exposition of Rome, E42 (also known as EUR, Esposizione Universale di Roma), set to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of fascism. Cini determined the future of EUR by advising Mussolini that the exposition be located in the Tre Font...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Notes on Contributors

- Interstitial, Pretentious, Alienated, Dead: Antonioni at 100

- Modernities

- Aesthetics

- Medium Specifics

- Ecologies

- Bibliography

- Index

- List of Illustrations

- eCopyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Antonioni by Laura Rascaroli, John David Rhodes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.