![]()

PART I

Things

Introduction

‘Things’ is one of those generic categories that, in spite of close scrutiny by philosophers over the centuries, seems nevertheless to have eluded any precise definition. Simply, it can be said to be a term that stands for the basic unit that makes up the totality of the material world. But in recognizing how culturally determined the manner in which the material world is formed and perceived, it becomes clear how impossible it is to arrive at an objective catch-all designation. In these days of postmodern uncertainty and cultural diversity, an awareness of difference and alternative interpretations is a much more achievable aim than trying to reach an ultimately conclusive definition. The first three chapters are therefore dedicated to establishing some working definitions of ‘things’ that start out as a conglomerate clutter of artefacts that make up the totality of the physical world not as a raw mass of matter, but as material culture with human associations in as much as it is informed by meanings as fundamental as identity, life and death. This is not to over-dramatize the role of things, since the choice to use this term was made on the assumption that, by definition, ‘things’ are non-special and mundane, but merely that which makes up the physicality of the everyday. As Henri Lefebre has written, ‘The everyday is the most universal and the most unique condition, the most social and the most individuated, the most obvious and the best hidden’ (Lefebre 1987: pp. 7–11). At the same time, even though ‘things’ described in this way are unobtrusive and escape attention, they are nevertheless instrumental in the literal and grounded sense of mediating the link between people and artefacts and therefore between the human worlds of the mental and the physical.

FIGURE 1 Woodwork bench with milk bottle (Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, photo: Mike Coldicott).

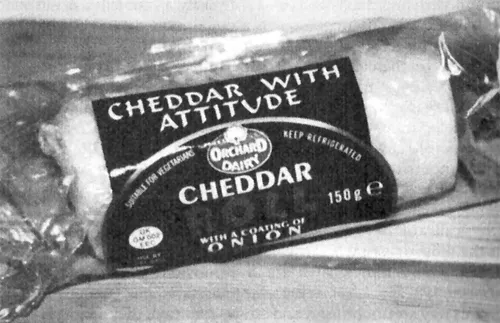

FIGURE 2 ‘Designer’ cheddar cheese.

![]()

1 The meaning of design: Things with attitude

The rise of material culture as a specific field offers a place for the study of the history and theory of design that refuses to privilege it as it is customarily seen, as a special type of artefact. By amalgamating design with the object world at large it becomes just one type of ‘thing’ among other ‘things’ that make up the summation of the material world – the objects of human production and exchange with and through which people live their everyday existence.1 Therefore it is against that broader context that design can be considered, where it forms part of the wider material world rather than separated off, encapsulating a small exclusive array of special goods. But it is not the ‘thing’ in itself which is of prime interest here, even though it is positioned at the central point of focus. The material object is posited as the vehicle through which to explore the object/subject relationship, a condition that hovers somewhere between the physical presence and the visual image, between the reality of the inherent properties of materials and the myth of fantasy and between empirical materiality and theoretical representation. The object therefore is both the starting point and the ultimate point of return, but overturning the usual interests of design practice by methodologically casting aesthetic visuality as subordinate to sociality. It is in the latter particularity that this project departs very distinctly from what could be characterized as conventional design studies which assumes ‘design’ to be at best a professional activity (designers know best) and at worst the result of a self-conscious act of intentionality (as in do-it-yourself).2 At worst, because the logic of design studies has been only to consider the ‘best’ examples along the conventions of modernist ideals of ‘form follows function’.3

But design can be defined much more broadly as ‘things with attitude’ – created with a specific end in view – whether to fulfil a particular task, to make a statement, to objectify moral values, or to express individual or group identity, to denote status or demonstrate technological prowess, to exercise social control or to flaunt political power. Therefore in demoting design by recontextualization and integrating it as one type of object among a more generalized world of goods that make up the totality of things makes it possible to investigate the non-verbal dynamics of the way people construct and interact with the modern material world through the practice of design and its objectification – the products of that process.

This chapter will explore some of the various definitions that have been attributed to ‘design’ that have gone towards excluding it from ‘things’ – the totality of entities that make up the material world and divided it off by hierarchical order and generic category to distinguish design as a privileged type. The object of the exercise, in more ways than one, will be to dislocate design from the habitual aesthetic frame devised by conventional art and design historical and theoretical studies, to present it as just one of the many aspects of the material culture of the everyday. But before setting out to explore the wilder outer reaches beyond design’s own territory, this chapter will first review as a starting point the more circumscribed definitions of design,4 its history and some of the literature that has established it as a certain type of object and process. It will then redefine design so as to be able to accommodate more popular forms and ordinary objects to establish a more level playing field in which the interrelations between extraordinary designed objects can be considered alongside ordinary ‘undesign’. This more inclusive redefinition of design will be used to frame the discussion within the ‘culture/nature’ framework that distinguishes cultural artefacts, such as chairs, from natural things like trees. The pairing of chairs and trees is particularly apposite in that chairs have traditionally been made out of trees, transformed by the process of design from organic entities into material culture. Design is the touchstone of modernity that differentiates between ubiquitous vernacular forms, tools and craft practices that have evolved gradually and unconsciously over thousands of years, and the spirit of innovation that has animated designers to turn away from the habitual traditional materials and modes of making to objectify new technologies and social change.

The conventions of design studies5 have established a simplistic frame of reference based on the concept of ‘good design’ in opposition to ‘bad’ design that has tended to act as an automatic diagnostic censor to pluck out any subject considered beyond the pale. Therefore a prime task for this chapter will be to critique and locate the ‘good design/bad design’ debate within a specific historical context in order to extend and redefine design as a non-generic common process and thus to integrate it into the larger material world of goods.

When modern products termed ‘design’ are recontextualized as an aspect of material culture, they lose their visibility to become part of the ‘everyday’. The aim is to expand the definitions of design so as not only to include its more usual role of ‘things with attitude’ but also to include a consideration of it as a process through which individuals and groups construct their identity, experience modernity and deal with social change.

Chairs don’t grow on trees: Defining design

The chair (which assists the work of the skeleton and compensates for its inadequacies) can over centuries be continually reconceived, redesigned, improved and repaired (in both its form and its materials) much more easily than the skeleton itself can be internally reconceived, despite the fact that the continual modifications of the chair ultimately climax in, and thus may be seen as rehearsals for, civilization’s direct intervention into and modification of the skeleton itself.6

Somehow there is something quite natural about ‘things’. Things seem to have always been there, defining the world physically – through such objects as walls that determine boundaries separating spaces and doors that give or prevent access. Things are ubiquitous like furniture that gives support to our bodies when we sit down, and paths that direct our feet where to walk, vehicles that transport us as we travel about on the daily round. Things lend orientation and give a sense of direction to how people relate physically to the world around them, not least in providing the physical manifestation, the material evidence of a particular sense of group and individual identity. Things don’t necessarily call attention to themselves and are only noticed if not there when really needed. Their presence is incontestable; yet it is only in the naming of things – ‘chair’, ‘car’, ‘coat’, ‘toothbrush’, ‘escalator’ – that they assume a particularity that makes them stand out as individual entities from against the background of the general physical environment, as seemingly ‘natural’ as the very ground we walk on. This rather basic definition does not mean to ignore the literature that attends to the definition of the perceived world such as Ludwig Wittgenstein’s philosophy of mind. Particularly valuable in this context is his preoccupation with ‘the important questions of everyday life’ as represented in his Philosophic Investigations 7 which concentrated on the role of language in the perception and expression of the relationship between the objective world and human thought. Wittgenstein’s interest in philosophical propositions which set out to define reality drew a direct correlation between words and tools as instruments of meaning, giving greater importance to the process of language in the context of space and time than attempting to arrive at essentialist definitions.8 But although the meaning of the object world is elucidated by such studies, just as semiotics has done so much to increase our knowledge of visual culture, the non-verbal nature of the material world referred to in this project cannot entirely be explained through language.

But the ‘thing’ as made-object is not natural, although it may appear so because there is nothing very special about it. Its presence alone does not lend it visibility, rather like the mystery of Poe’s ‘Purloined Letter, it eludes detection while staring the searcher in the face because it is ‘too self-evident’. You have to be looking to find it. In Poe’s famous short story, the compromising document was only found when the searcher ‘came with the intent to suspect’.9 ‘Thing’ is a term so obvious it needs no definition and can therefore ostensibly stand in for absolutely anything. Yet in so doing it might also be alleged that ‘things’ means absolutely nothing. But because things have no special attributes, their ubiquity defies definition and makes them appear natural. ‘Thingness’ lends artefacts an elusive quality through which it is possible to start to examine the particularity of the significance of the object world within the context of the social world. What then distinguishes ‘things’ from ‘design’? Although design is a noun denoting things, it is also a verb – a self-conscious activity devoted to creating new forms of artefacts and therefore a conceptual as well as a manufacturing process that arose from a modern mentality that turned its back on the past and believed in the possibility of progress through change.

Things do not have the high-profile visuality of ‘design’. It is only when a thing acquires a name that an artefact announ...