- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book provides original grounds for integrating the bodily, somatic senses into our understanding of how we make and engage with visual art. Rosalyn Driscoll, a visual artist who spent years making tactile, haptic sculpture, shows how touch can deepen what we know through seeing, and even serve as a genuine alternative to sight. Driscoll explores the basic elements of the somatic senses, investigating the differences between touch and sight, the reciprocal nature of touch, and the centrality of motion and emotion. Awareness of the somatic senses offers rich aesthetic and perceptual possibilities for art making and appreciation, which will be of use for students of fine art, museum studies, art history and sensory studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Sensing Body in the Visual Arts by Rosalyn Driscoll in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

By the Light of the Body

1

Sight and Touch

I’m sitting in front of a sculpture that’s completely unknown to me. I’m going to explore it entirely through touch—blindfolded—which seems difficult if not impossible.

Seeing allows me to assess a situation so I know how to meet it, where to be, and what stance to take—defensive, receptive, open, or reserved.

With sight, in one instant I have a visual imprint.

But in these conditions I can’t anticipate what lies ahead. Before I even touch whatever’s in front of me, I discover an important aspect of touch: I must initiate the contact and reach out. There’s risk in the gesture and control in the choice. Touching is such a risk-taking experience. I’m so excited. Anything could be out there.

My fingertips touch a hard, flat surface. I feel the slight shock of meeting something different than what I had imagined.

Two feelings come to me when my hands touch the surfaces: one of disappointment and the other of pure joy. Disappointment in the fact that I was expecting something dramatic, maybe even gross. And the joy was that this is not dramatic, it is calm and soothing.

I also feel the shock of breaking the taboo against touching art. I feel really guilty touching these sculptures, like some large hand is just waiting to swat. That really intensifies my sense of touch. First comes the strange fear and thrill of breaking the hovering taboo of “Don’t touch the art.” And once broken, a whole new world comes to life.

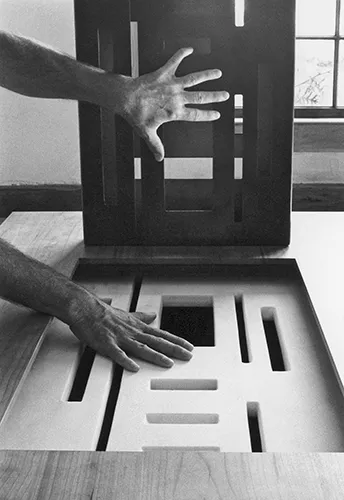

Figure 1.1 The vertical steel box and the horizontal marble slab mirror each other, as do the hands. Hands can also descend through the openings in the marble slab to touch a horizontal slab of rough schist a few inches below. Elegy 1, 1995, Wood, marble, schist, steel, handmade paper, 53 × 31 × 50 in. Copyright © 2020, Rosalyn Driscoll.

Seeing and touching are very different sensory modes. But the differences between seeing and touching extend beyond their perceptual roles. Sight and touch are different ways of knowing. We say I see to mean I understand. We say something is touching to mean I am emotionally affected. We link sight to comprehension and touch to emotion: sight to brain, touch to heart. Why do these two sensory modes relate to such different aspects of the body-mind? How do they, and the dimensions they reveal, relate to each other? How do they conflict? What do the experiential differences between sight and touch have to do with the lines we draw between reason and emotion or mind and body?

These sculptures make me think about the difference and similarity and overlap of the senses—the way one touches with eyes and looks with fingertips.

To distinguish and highlight the differences between sight and touch, I will simplify and generalize both sensory modes. Both sight and touch will be characterized here as if they were used in isolation from each other, as if sight were operating without touch and as if touch were used without sight. For the moment, they will be cast in opposition in order to heighten their differences. We must remember, however, that the nature of sensory perception proves more complex and variable than speaking of them separately would suggest. In reality, the two senses work in concert and in dialogue. They complement and support one another. Sight always contains haptic information and haptic memory even when we are not touching. Touching triggers visual imagery even if we are not looking. Furthermore, some of the differences between sight and touch lie not so much in kind as in degree, working at different scales of size and time.

My descriptions of sight and touch are inevitably shaped by my cultural biases as a middle-class, Midwestern, white, American woman born at the end of the Second World War. The cultural, social dimensions of the senses are beyond the scope of this book, but they underlie all my investigations. Even the use of such concepts as sight and touch remains culturally dependent. Other cultures and other eras have conceived sight, touch, and the senses differently than the culture and time I represent. As a result, they literally perceive differently. In the largest context, all perception is shaped, organized, and informed by a social, cultural environment. Sensory anthropologist David Howes corrects our misconceptions of perception as private, internal, ahistorical, and apolitical:

The human sensorium. … never exists in a natural state. Humans are social beings, and just as human nature itself is a product of culture, so is the human sensorium. … Tastes and sounds and touches are imbued with meanings and carefully hierarchized and regulated so as to express and enforce the social and cosmic order … Perception is not just a matter of biology, psychology or personal history but of cultural formation. (Howes, 1991, 3–4)

The project to explore art through touch grew out of my resistance to the dualisms and oppositions that my culture has instilled in my consciousness and that shape my perception. The list is endless and includes: human/nature, man/woman, white/black, rich/poor, right/wrong, progress/tradition, and so on. In each pair, the first concept traditionally dominates the second. I have learned to question the dominant power in each pair and to explore the minor character, in order to raise its status and honor its possibilities. Ultimately, I hope to achieve a more dynamic balance and to transcend duality altogether. My artwork and this book represent my efforts to forge a more unified field of the dueling pairs that have defined my artistic pursuits: sight/touch, object/environment, outside/inside, human/nature, and mind/body.

Touch has been cast as a minor sense in our culture. Its powers are often unappreciated and misunderstood. Touch is not usually isolated from sight, sight often occurs without touch, and touch usually functions unconsciously. For these reasons, most people remain unaware of the qualities peculiar to the sense of touch. More is implicated in the differences between sight and touch than meets the eye or hand. Sight and touch are not simply the means for gathering sensory information. Each embodies a different way of knowing. Each creates a different version of reality. Our concept of reality determines how and what we perceive. What we perceive further informs the sense of reality, in a cycle of continuing construction. Out of this construct of reality, we create selves, bodies, identities, behaviors, worldviews, arts, laws, religions, wars, and cultures. Which sensory systems we cultivate has profound, far-reaching implications.

Unaware of the qualities and effects unique to the sense of touch, and accustomed as they are to visual ways of knowing, people who touch my sculptures blindfolded are often surprised.

I remember the sculptures kinesthetically but not so much visually, and I usually have strong visual memory. I remember a deep hole in one, and going down that hole, but it didn’t look that deep. What I remember is the way it felt, not the way it looked.

When I looked it felt cold. It felt warm when I touched.

You can’t tell how it feels by looking at it.

The visual system is concerned with salience, orientation, arousal, attention, and identification. The haptic system attends to safety, motion, spatial orientation, and self-definition. Yet visual and haptic perceptions usually occur in tandem, fusing to create a unified impression, which we assume to be visual in nature. When impressions from sight and touch conflict, one or the other can dominate or at least modify the other, depending on the situation. We remain unaware of the exact mix of seen and felt.

The seemingly objective quality of sight and the importance we bestow on sight make it the measure of reality. We tend to assume that what we see is true, real, and the whole story.

We take in so much visually and then think we know it.

Most of us believe that looking is simply a matter of visual recording. The popular notion of the eye as a camera posits that seeing imprints images on the retina, like light on film, faithfully recording everything within the field of vision. Yet sight is highly selective in what it chooses to see and how it responds to those choices. Like all perception, seeing is driven by our conscious and unconscious desires, interests, and needs. We select what we see depending on what is relevant or important to us. In fact, we see very little. We usually focus only on what matters, what is striking, what is anomalous, or what is familiar. How we interpret and assess what we see is shaped by our personal, social, and cultural histories. While we assume that other people are seeing things the same way we are, the person next to us is most likely seeing quite differently—selecting different things, seeing them in different ways, and giving them different meanings. Yet seeing seems to provide an objective picture. Because the physical activity involved in seeing is so minimal and so subtle, seeing seems to give us the object rather than the activity of seeing. We seem to pass directly to the object as if there were no perceptual process intervening. On the other hand, touching gives us both the object and the actions that form the object.

Seeing is a distance sense. We have the ability to see far and globally. We effortlessly traverse an enormous range of visual space, from remote to close, spanning the interval between faraway mountains and the glass at hand within a single glance. We can focus on a particular tree while also taking in the surrounding forest with peripheral sight. To look at some things in their entirety, especially large ones, we must actually maintain a certain distance. If we are too close, we see only part of something, or we see it with distortions. Works of art are usually meant to be seen as a whole and therefore at some distance. Much of the power of Richard Serra’s huge steel sculptures that wrap around or cut through space lies in our inability to see them all at once, especially indoors; we come to know them in motion, over time, with our bodies as much as with our sight.

The distancing capacity of sight can remove us from what we see, not only physically but also emotionally and conceptually. Perceptual psychologist Rudolf Arnheim describes the power of sight to remove us from engagement:

To be able to go beyond the immediate effect of what acts upon the perceiver and of his own doings enables him to probe the behavior of existing things more objectively. It makes him concerned with what is, rather than merely what is done to him and what he is doing. Vision … is the prototype and perhaps the origin of teoria, meaning detached beholding, contemplation. (Arnheim, 1969, 17)

While sight gives us the ability to observe without entanglement, this distance proves a double-edged sword. We think of ourselves as separate from what we see. The seen object remains aloof, independent, beyond us. This physical and psychological distance can breed a feeling of disconnection. And that which is seen can more easily be objectified.

Feeling with my eyes open was more distant. My brain was working. The sensory fell away and was less intense.

I realize how much I rely on my eyes to define and objectify my world. Sight can actually be a handicap and can distance me from truly experiencing something on a deeper level. In that way sight is similar to language. Words can distance me from an object or an experience in a peculiar way.

Distance is a profound experience in our perceptual and psychological development. As children grow, the distance from the mother, central to their sense of reality and safety, is carefully, experientially measured. At first, the distance is as close as possible, skin to skin. As children learn to move independently, they maintain visual or auditory contact with the mother, making repeated returns to the mother’s body for tactile reassurance, closely assessing the gradually lengthening distance from their mother, learning the spatial, distance senses through the fluctuations of space and distance in this highly charged fundamental relationship. Sight as a distance sense remains colored by this basic movement of independence away from the tactile refuge of the mother. Touch remains colored by the assurance and comfort afforded by the embrace and nourishment of the mother.

There are so many emotions attached to the closeness and innocence of touch.

Seeing seems one-sided rather than reciprocal or mutual. Seeing can even give us a sense of power or dominance, as if remaining unaffected by what we see allows us to control it. Sight confers a degree of invincibility, potentially isolating us in the chamber of our thoughts and fantasies. British writer Gabriel Josipovici wrote a literary meditation called Touch in which he describes our habitual way of seeing:

[Seeing is] our way of establishing our connection with the world: through viewing, or having views of it. Our condition has become one in which our natural mode of perception is to view, feeling unseen. We do not so much look at the world as look out at it, from behind the self. (Josipovici, 1996, 43)

The words viewer and spectator are commonly used to describe someone looking at art. As Josipovici notes, these words connote sight, distance, and point of view. Because those are the very qualities transformed, by touching, into intimacy, proximity, and mobility, I avoid using such terms to describe the people who touch my sculptures. Even for people who perceive artwork visually, haptic perception is subliminally present. Words such as viewer fail to acknowledge the haptic dimension of the aesthetic experience. The word perceiver is a bit awkward and not in common use but closer to the truth.

Touch, by definition, brings us into intimate contact with the world. We meet the world and let it in. Sight reinforces the hermetic privacy of separate selves, while touch confirms the palpable existence of a world pressing on us as we press upon it. The boundary between bodies and objects, and self and other, melts.

Touch is so immediate and personal. I hear things and smell things that I do not when I only look.

Touching calls for a stronger level of commitment than looking, as Josipovici writes:

Sight is free and sight is irresponsible. I can cast my eye to the far horizon and then back to the fingers I hold up before my face, all in a fraction of a second and with no effort at all. … On the other hand, were I to walk to that point on the horizon it would take time and effort. … To look cost me nothing but to go involves both a choice and a cost. (Josipovici, 1996, 9)

The investment made by the walker costs more but also yields more, as he takes in the whole landscape along the route, knows his body moving, and feels the textures of the ground and the changing contours of the land as he walks, climbs, and descends. Such actions, although very different in scale and effort, resemble touching an artwork—the physical resonance with the contours, the way it evolves over time, and the unfolding narrative. Touch engages one in an embodied journey rather than viewing from a distance.

The space encompassed by sight can be vast, yet, ironically, the ease of eye movement generates a less defined, less felt sense of space than that known through touch. The space accessible to touch is limited to what we can reach; haptic perception remains bound to the sphere of the body. Spatial knowing through haptic exploration, though more limited in range than sight, is more vivid. It registers in the body.

When you look, it’s an object. When you touch, it’s a journey.

The spatial limitation, the commitment, and the vividness of touching art encourage concentration, focus, a deepening of perception.

There’s no distance; looking at abstract art can be distancing.

Touching may even amplify visual qualities.

I had visually explored the sculptures a month ago, and knew what the forms were. Yet going through the exhibition without sight, the forms seem much larger, deeper and wider.

The distance of sight makes for a more global grasp, but usually of lower intensity. Tactile proximity offers an experience that may be higher in intensity and intimacy but lower in comprehension. Hans and Shulamith Kreitler, in Psychology of the Arts, suggest that “vision affords an acquaintance without complete encounter, while tactility provides for an encounter without complete acquaintance” (Kreitler and Kreitler, 1972, 208).

Sight and touch pick up different qualities in things. David Katz, pioneer researcher into haptic perception, notes that touch takes us inside the object, reveal...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part 1: By the Light of the Body

- Part 2: Body and Art in the World

- Bibliography

- Index

- Imprint