![]()

1 Introduction: Echoes of a Cry

Towards the end of Meghe Dhaka Tara, we see the protagonist, Neeta, on the grounds of a sanatorium for tuberculosis patients in the hill station of Shillong, far away from the grimness of her family home in a refugee colony near Calcutta. She sits quietly on a rock as her brother, Shankar, who has come to visit her, tries to distract her with cheerful chit-chat about the family, especially about the mischievous antics of their young nephew, Geeta and Sanat’s son. Suddenly, the usually stoic and reserved Neeta cries out, ‘But I did want to live!’ and breaks down, clinging to her brother, imploring him to assure her that she will live: ‘Please tell me that I’ll live, just tell me once that I’ll live! I want to live! I want to live!’ Her desperate yet defiant cry echoes through the landscape, as the camera pans across the surrounding mountains in a dizzying 360-degree turn. Even after her visual image disappears from the screen, Neeta’s disembodied voice reverberates in an empty space – and continues to do so in the Bengali cultural imaginary. A recent Bengali newspaper article claims, in appropriately melodramatic terms, that Neeta’s piercing cry ‘has not only echoed through the hearts of Bengalis as a lament but over the last fifty years, continued to inspire cornered men and women whose hopes have been extinguished’.3

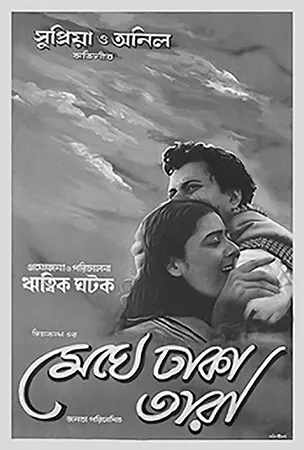

Neeta’s outburst: ‘I want to live!’

Original poster (Artwork: Khaled Choudhury)

For many viewers familiar with the film’s historical and cultural milieu, including myself, Neeta’s final, uncharacteristic outburst of anguish evokes the thwarted desires and shattered dreams of a generation of displaced Bengalis caught in the crossfire of history. This generation was not a historical abstraction to me as my parents and some of our closest family friends belonged to it. On seeing Meghe Dhaka Tara for the first time in my teens, I was struck by the haunting parallels between Neeta’s story and the lives of two of my favourite aunts: one of my mother’s dearest friends and her older sister. Brilliant, articulate and imaginative students who were encouraged by their liberal middle-class family to pursue higher education, they had to give up on their dreams of becoming a historian and an economist, respectively, in their late teens to shoulder family responsibilities in the wake of the Partition and their father’s death. They worked as schoolteachers as they put themselves through college and raised their younger siblings, and then until retirement; never married; and spent their twilight years in a rented apartment, not having managed – despite their frugal lifestyle – to save enough to afford the security of a home of their own. Of course, they did not die young, like Neeta, nor were they crushed by their circumstances. They lived long lives, translating their left-liberal and proto-feminist principles into everyday practice; had a formative impact on the generations of high school students they taught and their surrogate nieces (my sister and I); and never spoke of their disappointments or displayed any hint of bitterness. Nonetheless, their faces get transposed onto Neeta’s every time I watch Meghe Dhaka Tara, and her final scream always reminds me of the broken dreams and lost horizons of hope that my aunts – and countless other women and men – had accepted in silence, with a quiet courage and heart-rending grace akin to Neeta’s habitual response to adversity.

Not surprisingly, given its social and emotional resonances and unsettling power, Neeta’s climactic lament is routinely invoked in tributes to the film’s director Ritwik Ghatak and in conversations about his films. It is perhaps fitting that this cry of pain and defiance has become emblematic of the oeuvre of a film-maker who repeatedly described cinema as a means for ‘expressing my anger at the sorrows and sufferings of my people’4 and as a medium that let him ‘shout out’5 and give voice to ‘the screams of protest’6 that had ‘accumulated’ in his psyche as a result of observing the iniquities around him.

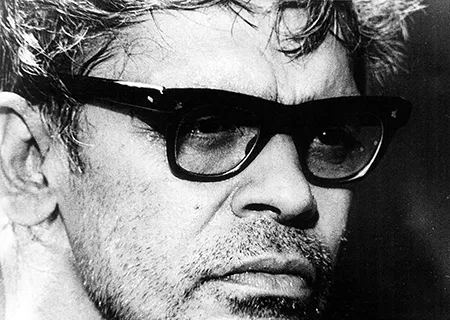

Ritwik Ghatak (1925–76)

Ghatak, who came of age in Calcutta in the 1940s, tended to blame the social, political and economic woes of contemporary Bengali society on what he called ‘the great betrayal’: the Partition of the Indian subcontinent in August 1947, which led to the creation of the new sovereign nation-states of India and Pakistan and was accompanied by widespread communal violence, resulting in the deaths of approximately 500,000–1 million people, and one of the largest mass displacements in modern history, involving an estimated 12–15 million people. Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s Urdu poem ‘Subah-e-Azadi’ (‘Dawn of Freedom: August 1947’) captures the widespread sense of disenchantment, on both sides of the newly drawn border, over the traumatic terms on which independence from British rule had finally been won:

These tarnished rays, this night-smudged light –

This is not the Dawn for which, ravished with freedom,

We had set out in sheer longing…

Night weighs us down, it still weighs us down.

Friends, come away from this false light. Come, we must search for

that promised Dawn.7

The horrors and the tragedy of the Partition – the loss of lives, livelihoods and ancestral homes, and the abrupt sundering of families, communities and emotional bonds – darkened the long-awaited ‘dawn of freedom’ on the Indian subcontinent. Like Faiz and many others of his generation (including my left-liberal parents and their extended family of friends), Ghatak was deeply disturbed by the way in which the Partition seemed to negate or vitiate the promise of the nationalist movement for independence. Until his untimely death in 1976, he continued to agonize over its far-reaching social, cultural and political consequences, especially for the people of Bengal, his home province and one of the regions hardest hit by the Partition.

Undivided Bengal, which occupied a total area of 78,389 sq. miles and was perceived in British India as a region where religious differences between the Hindu and Muslim segments of the population were subsumed within a Bengali cultural and linguistic identity, was carved into two separate territorial entities in 1947: Muslim-majority East Bengal, which formed the eastern wing of Pakistan, and West Bengal, which became a state of the federal republic of India. Bengal’s much-vaunted cultural unity lay in tatters, unravelled by sectarian sentiments and Hindu-Muslim riots, and overnight, Bengalis such as Ghatak, who lived in or migrated to West Bengal but had deep roots in East Bengal (or vice versa), saw part of their homeland become a foreign country. While nearly 42 per cent of undivided Bengal’s Hindu population remained in East Pakistan at first, continuing communal tensions led to a steady influx of Hindu refugees, including a large number of middle-class migrants, into West Bengal from 1948 onwards, creating staggering problems of resettlement by the 1950s and exacerbating the socio-economic troubles of an already overcrowded, resource-strapped state. This process continued throughout the 1960s; in 1981, the number of East Bengal refugees in the state was estimated to be 8 million or one-sixth of the population.8 A large number of these refugees settled in or around Calcutta, taking over marshy land in the eastern fringes of the city to build ‘refugee colonies’ – ramshackle settlements similar to the one we see in Meghe Dhaka Tara – and struggled to rebuild their lives from scratch with little or no assistance from the state.9 The government’s failure to create an effective refugee rehabilitation programme not only impinged on the everyday lives of millions of displaced Bengalis but also significantly contributed to West Bengal’s economic decline, political turmoil and social anomie in the post-1947 period.

The post-independence plight of a ‘divided, debilitated Bengal’ haunted Ghatak. It was a plight made all the more poignant by his memories of the cultural and political vibrancy of Bengal in the 1930s:

In our boyhood, we have seen a Bengal, whole and glorious. Rabindranath [Tagore], with his towering genius, was at the height of his literary creativity, while Bengali literature was experiencing a fresh blossoming with the works of the Kallol group [a group of modernist writers], and the national movement had spread wide and deep into schools and colleges and the spirit of youth. Rural Bengal, still reveling in its fairytales, panchalis [narrative folk-songs], and its thirteen festivals in twelve months, throbbed with the hope of a new spurt of life. This was the world that was shattered by the War, the Famine, and when the Congress and the Muslim League brought disaster to the country and tore it into two to snatch for it a fragmented independence. Communal riots engulfed the country … Our dreams faded away. We crashed on our faces, clinging to a crumbling Bengal, divested of its glory. What a Bengal remained, with poverty and immorality as our daily companions, with blackmarketeers and dishonest politicians ruling the roost, and men doomed to horror and misery!10

As the eminent writer and activist Mahasweta Devi (who also happened to be his niece and childhood playmate) pointed out, Ghatak’s view of a prelapsarian Bengal was tinged by his childhood experiences and class privilege, and the seeds of Bengal’s post-independence predicament had actually been sown long before the Partition. Nonetheless, as she also acknowledged, after the Partition ‘the problems did become more acute … and the situation disastrous’.11 To be fair to Ghatak, he was fully aware of how class divisions and the dominance of the Bengali Hindu middle classes over Muslim peasants and labourers had partly paved the way to the Partition of Bengal, and also deeply critical of middle-class political and social stances.12 What bothered him most about the Partition was not the loss of class privilege that it entailed for the middle-class refugees from East Bengal (whose plight features prominently in his films and in contemporary literature about the Partition) but what he described as ‘the division of a culture’ and its radioactive cultural and emotional fallout.13 In his director’s statement on Subarnarekha, he said that he used the word refugee or displaced person, not to ‘mean only the evacuees of Bangladesh’ but in a ‘more generic sense’ as well: ‘In these times all of us have lost our roots and are displaced – that’s my statement.’14 The problem, as he saw it, was not only socio-economic but also one of cultural deracination and spiritual homelessness. His preferred Bengali word for ‘refugee’ was udbastu, which literally means someone displaced from an ancestral home (bastu) or foundations and emphasizes the violence of uprooting rather than the act of seeking refuge. He ascribed far-reaching consequences to the resultant sense of rootlessness: ‘People’s ways of thinking have changed, their hearts have changed, their souls have changed … their cultural consciousness has putrefied, and their umbilical ties with their past completely severed.’15

An abiding preoccupation with the Partition’s corrosive impact on the intimate and quotidian aspects of middle-class life in post-independence Bengal marked Ghatak’s cinematic oeuvre (and, indeed, his life). In almost all of his films, and especially in the three that came to be seen as constituting his Partition trilogy – Meghe Dhaka Tara, Komal Gandhar and Subarnarekha – the foundational national trauma of the Indian subcontinent – ‘the nightmare from which the subcontinent has never fully recovered’, as historians Sugata Bose and Ayesha Jalal put it – is seen through the lens of this specific regional reality. He took it upon himself ‘to present to the public eye the crumbling appearance of a divided Bengal, to awaken the Bengalis to an awareness of their state and a concern for their past and the future’.16

Cinema in the shadow of the Partition: ‘The Outsider’ (Artwork: Avik Kumar Maitra)

This thematic obsession drove the visionary experiments with film form that have secured Ghatak the admiration of cinephiles not just in India but worldwide, and a reputation for reinventing the grammar of cinema.17 Ghatak’s experimental urge ‘to find the limit, the end, the border, up to which the expression of film can go’18 was also a deeply political one, stemming as it did from what he described as his ‘commitment to contemporary reality’ and his desire to ‘portray my country and the sorrows and suffering of my people to the best of my ability’.19 Rather than being ends in themselves, his formal innovations were part of an attempt to forge a cinematic idiom capable of not only registering the devastating emotional impact and continuing socio-economic aftershocks of a historical trauma often assumed to be beyond the scope of conventional codes of representation, but also of jolting Bengali viewers, his primary target audience, into a critical engagement with their contemporary reality. This dual objective partly accounts for the stylistic hybridity of Ghatak’s films, which combine melodramatic force with a modernist aesthetics of fragmentation, and move with a disorienting fluidity between the representational logic of screen realism and the expressive potential of stage performance.

In my reading of Meghe Dhaka Tara, I locate its unsettling power in the ‘cinematic theatricality’ that emerges from this kind of dynamic oscillation between seemingly antithetical modes. I use this term to refer to a theatricality – or an ensemble of visual and aural effects evoking the artifice and drama of theatrical performance – that is also intensely cinematic, contrary to conventional understandings of the theatrical as anti-cinematic. It is ‘a mode of address and display’20 that, as I show in Chapter 4, emerged out of a creative collision between the stage and the screen, between Ghatak’s ideas about film form (partly shaped by Calcutta’s incipient film society movement of the 1940s) and his experience as an activist in the leftist theatre movement of the late 1940s to early 1950s. Using the lens of cinematic theatricality to analyse Meghe Dhaka Tara brings into view not just Ghatak’s modernist experiments with melodramatic devices (the chief focus of scholarly writings on Meghe Dhaka Tara so far21) but also the originality of his cinematic language, the film’s fluid movement between the theatric...