![]()

1 Folkestone Turned: Of Fault-Lines and Fairy-Tales

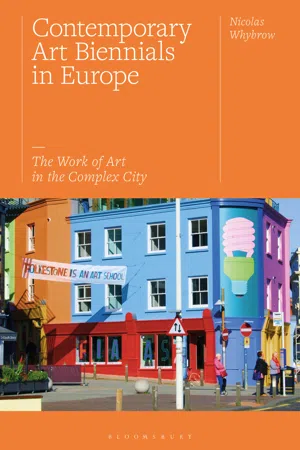

‘FOLKESTONE IS AN ART SCHOOL’ proclaimed a large colourful banner draped over the side of the town’s inner harbour wall as you looked out towards the old harbour arm and station, still undergoing major renovation work in the late summer of 2017. If you then swivelled slightly to your left, allowing your gaze to travel up to the top of the nearby Eastern cliffs, one of Folkestone’s five Martello lookout towers – built at the start of the nineteenth century to pre-empt a possible Napoleon invasion that never materialized, of course1 – displayed the same slogan in even larger lettering, just to make sure any passing boats got the message (Figure 1.1). And, with a further quarter turn, your back now to the sea, the statement again, several times over: painted on to the low white wall bordering an island of flowers and plant life on Harbour Street, strung across the lower end of Old High Street, and then on vertical banners at intervals all the way up the central drag of Tontine Street. If you’d arrived in Folkestone by train, a huge billboard at the station entrance, bearing the self-same motto, will have been the very first thing to greet you as a visitor, immediately offering you one possible frame through which to contemplate the town, one that implicitly posed the question: by virtue of what exactly could the town of Folkestone be called an art school?

FIGURE 1.1 FOLKESTONE IS AN ART SCHOOL (2017), Bob and Roberta Smith, 15th September 2017

The intervention was the work of that past-master of polychrome, DIY sandwich-board messaging, Bob and Roberta Smith (just a single person, of course) and only one of four component parts of his Folkestone Triennial 2017 project commission, though certainly the most visible one in the context of the urban environment. The other three elements incorporated, first, a series of twelve short how-to-go-about-making-art video films, featuring the artist as inspirational teacher. Second, the creation of a ‘Faculty’ running a programme of art instruction during the Triennial for a selection of committed pupils from the town’s high schools and colleges. This involved a large, multi-skilled team of resident artists, with work and exhibition space – open and accessible to the public – at the Triennial’s former visitor centre on the corner of Tontine and Old High Streets (where the artist’s dozen videos were also on show).2 And, third, a ‘Directory’ of all the many and varied art-based initiatives and facilities existing in the meantime in the central Creative Quarter of Folkestone: from adult education at The Cube building at the north end of Tontine Street,3 to the work of local community artists Strange Cargo – whose presence in the town predates by several years the move to commence serious regeneration initiatives at the onset of the new century – to the Folkestone Fringe which was inaugurated in 2007, in anticipation of the first Folkestone Triennial the following year, as an artist-led platform for nurturing local arts events and activities on an ongoing basis.

These four components combined already give a hint of the sheer volume and breadth of contemporary art practice and arts-based learning taking place in Folkestone and, therefore, begin to reveal what Bob and Roberta Smith was getting at with FOLKESTONE IS AN ART SCHOOL. Struck by the concerted efforts on the part of the local Creative Foundation (renamed Creative Folkestone in 2019) – which instituted the Triennial in 2008 and has substantially funded it ever since – to establish creativity, the arts and education as the drivers of urban regeneration in Folkestone, the artist resolved to make an artwork that would constitute a response to the challenge implicitly thrown down by those particular emphases. His multi-part intervention is, then, first, a form of acknowledgement of the noticeable infiltration of a revitalized cultural life into the town in a relatively short space of time and, second, a kind of advertisement for the intrinsic creative potential lurking in the place – extant arts activity apart – in terms of its history, its geological and geographical morphology and its current socio-cultural ‘life’. All of these reveal it to be very much a town living within the tensions of several spatio-temporal and cultural-political meeting points, be that where the land converges with the sea, the UK intersects with continental Europe, the more salubrious western half of Folkestone borders its run-down eastern counterpart along a north-south spine right in the town’s centre, or where a thriving past identity as popular seaside resort, inaugurated in the nineteenth century, encounters the beginnings of what turn out to be a drawn-out decline in the latter part of the twentieth century. But if those instances all represent one form of conceptual ‘edge’ addressed by Bob and Roberta Smith’s art school take on the town – to bring into play the 2017 Triennial’s governing theme of ‘double edge’ – the other is surely to proffer Folkestone as an example of creative inspiration to the broader art world and implicitly declare ‘there’s a lot artists can learn from this place, actually – about art, but also about the state of things in the UK at this moment in time’.

There have been a few instances in recent times of curators or commissioned artists using their exhibition briefs effectively to set themselves up as alternative ‘art schools’ – generally parading under the banner of ‘new institutionalism’ – as a way of asking fundamental, socially-engaged questions about what art is for and, therefore, how it should be taught. In other words, the art school as artwork. The failed 2006 Manifesta exhibition in Cyprus, later resurrected in Berlin, famously comes to mind, as do experiments by the likes of Tanya Bruguera and Thomas Hirschhorn (see Bishop 2012; Voorhies 2017). While such critical questions may similarly underpin FOLKESTONE IS AN ART SCHOOL, the impulse for the endeavour is rooted far less in formal theories of pedagogy and the socio-cultural critique of institutions (often enacted for the benefit of an already educated ‘art audience’) than in a playful, down-to-earth, hands-on nurturing of creativity in a way that anyone can identify with. Watching Bob and Roberta Smith ‘at play’ in his studio or roving the streets and beaches of Folkestone in his video films is a bit like spending quality time with a favourite uncle as he potters resourcefully and intuitively in his garden shed, opening your eyes to all kinds of weird and wonderful creative possibilities using the most everyday of materials, often in the form of discarded junk or based on chance juxtapositions. Even the ‘homework’ the artist issues at the end of each film comes over as inspirational: a task one is eager to fulfil rather than a self-consciously pedagogical chore. ‘We are the stuff around us’, the artist declares in one film entitled What Is That?, implicitly pointing the viewer in the direction of the potential that is to be unearthed in the town. And, while the approach appears straightforward and effortless in his performance, there is nothing facile about it. The artist’s disarming gift is that he can subtly introduce the most complex questions of art, humanity and urban living in the most quotidian way, thereby paving the way for creativity to infiltrate and flow naturally in the collective practices and consciousness of the town – as if it belonged. The deeper political implication is that the making of art is inherently humanizing, inclusive and democratic, and therefore has the capacity to lead people away from damaging, corrosive and constrictive ways of thinking and acting.

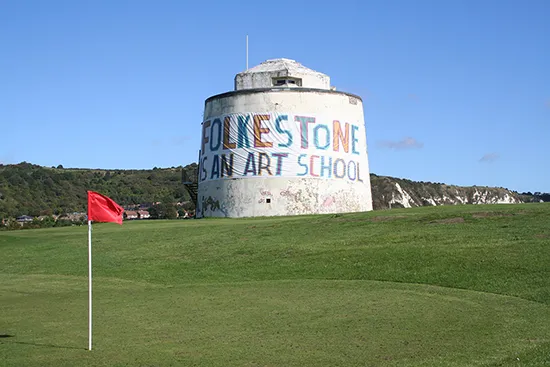

Returning us to the hub of FOLKESTONE IS AN ART SCHOOL, which is the ‘open space’ at 3–7 Tontine Street, Michael Craig-Martin’s 2017 ‘double edge’ commission Folkestone Lightbulb seemed to capture perfectly the spirit and moment of the town’s recent resurgence (Figure 1.2). Positioned effectively at the gateway of the emerging Creative Quarter, the simple, enlarged outline of a coiled energy bulb in shades of pink, blue and green adorned the narrow corner façade of the building in which Bob and Roberta Smith’s ‘Faculty’ had based itself on the ground floor. The façades of the building as a whole had been divided into separate, rectilinear panels of vibrant colour – lilac, sky blue, orange and so on – forming a kaleidoscopic cornerstone to the Creative Quarter. It was – and remains – unashamedly an image of hope, illumination and inspiration, apparently celebrating at a level of representation the ‘Eureka moment’ at which someone had the bright idea of investing in the area’s rehabilitation via the arts, creativity and education. At the same time, it is an energy bulb and, therefore, suggests not so much the triggering of an instantaneous event at the flick of a switch as a delayed reaction, as something that warms to the maximum potential of its task in the fullness of time – a slow burn evolution. That in turn points to the imperative of a future sustainability: the implementation of this step change must not be merely a fad, a momentary upswing or, indeed, a prelude to exploitative gentrification, but an improvement that is both lasting and inclusive. An energy bulb, moreover, implies sensitivity to key factors relating to the sustainability of the environment, such as clean and renewable energies and climate change. As such the coiled form of Craig-Martin’s lightbulb not only signifies an appreciation of its aesthetic design but also warns of a direction or momentum that has the capacity to spiral either way: upwards or downwards.

FIGURE 1.2 Folkestone Lightbulb (2017), Michael Craig-Martin and FOLKESTONE IS AN ART SCHOOL (2017), Bob and Roberta Smith, 15th September 2017

Be that as it may, both Craig-Martin’s and Smith’s engagements with Folkestone in their respective ways assert the recognition of infusions and circulations of life-giving energies into the town and it is no coincidence perhaps that one of its famous historical sons and one-time resident is William Harvey of whom there is a statue overlooking the Channel at Langhorne Gardens. In 1628 Harvey made the revolutionary discovery, as Richard Sennett explains in Flesh and Stone, that ‘the heart pumps blood through the arteries, and receives blood to be pumped from the veins. This discovery challenged the ancient idea that the blood flowed through the body because of its heat’ (Sennett 1994: 257). Importantly, Sennett pinpoints the way such new-found knowledge of the internal workings of the human body on the one hand ‘led to new ideas about public health’ (256) and, on the other, became analogous with urban design. Thus, ‘Harvey’s revolution helped change the expectations and plans people made for the urban environment. […] Planners sought to make the city a place in which people could move and breathe freely, a city of flowing arteries and veins through which people streamed like healthy blood corpuscles’ (256). As such, the ‘desire to put into practice the healthy virtues of respiration and circulation transformed the look of cities as well as the bodily practices within them. […] Planners thought that if motion through the city becomes blocked anywhere, the collective body suffers a crisis of circulation like that an individual body suffers during a stroke when an artery becomes blocked’ (263, 265).

The latter sentiment certainly chimes with the perception of Folkestone at the advent of the twenty-first century, a town whose complexion had become positively anaemic so blocked were its circulatory systems. In short, Folkestone was a basket case in urgent need of tender loving care in a whole range of ways. What follows, then, is a brief contextualization of its circumstances: how the town arrived at such a point of decline and how it endeavoured to extricate itself. More importantly for our purposes: how the introduction of an international triennial of contemporary art in 2008 played its part in the ‘fairy-tale’ of regeneration.

Ruination to repair

As a ‘frontier town’ on the South-East Kent coast located, like its near and probably more famous neighbour Dover, at the narrowest crossing point to France, it is no surprise really that Folkestone’s origins can be traced back a long way to the Mesolithic era and, later, include the arrival of the Romans in Britain. The existence of a convenient river, running from its source in the North Downs above the coastline’s renowned chalk cliffs through the town to the English Channel below, underscores the point: even if the river is culverted these days, strategically this was a good place to build a settlement. And, although staying relatively contained in size – to this day it remains a town rather than a city, while nevertheless being decidedly urban in character – Folkestone’s significance through the ages, but particularly since the mid-nineteenth century, within the context of the UK as a whole should not be underestimated. Until the advent of an era of package holidays and cheap flights abroad in the 1960s, Folkestone had thrived for a century or so, in one incarnation at least, as a seaside holiday resort whose attendant facilities contributed significantly to sustaining the local economy. The town’s role as a place of leisure was reflected, for example, in the existence of a vast and popular amusement park in the Marine Parade area on its western seafront, with a funicular lift powered solely by gravity and water conjoining it with the popular Leas cliff-top promenade above;4 a coastal park and pebbled beach, with requisite bathing amenities stretching the length of the western undercliff; an extensive wood and wrought iron pier poking out into the sea; to say nothing of Sunny Sands beach at Coronation Parade on the other, eastern side of the harbour area. Facilitating the development of Folkestone as desirable, accessible resort had been the earlier arrival of the railways in the 1840s, which had created, in turn, the demand for the installation of these late nineteenth-century leisure features. Thus, the town was cast as an appealing place to visit and stay, with a broad spectrum of lower to upper classes looking to spend their holidays there or even take up residence. The Victorian and Edwardian splendour of monolithic grand hotels, still functional to some degree, is there for all to see along the promenade of The Leas on the western cliffs, with its fantastic views across the Channel.

The introduction of the railways during the course of the nineteenth century had witnessed the construction of the line from London to Dover – today the UK’s first high-speed route (HS1) – and, by century’s end, the beginnings of cross-channel ferry traffic to the European continent. The present-day harbour arm, a solid stone pier with a leftward knee-bend halfway along, whose construction led to the formation of Folkestone’s inner and outer harbours, had been acquired by the South Eastern Railway Company in 1842. Having bequeathed the town with what remains to this day the highest brick-arched railway viaduct in the world – set well back from the sea and looming large over the roofs of the town centre – the company proceeded to situate a curved two-platform railway station directly on the harbour pier at which passengers from London could step off their trains and straight on to ferries to Europe (and vice versa). Indeed, for a time trains such as the renowned Trans-Europe Orient Express – on its way to Istanbul via Paris and Venice – were able to trundle directly on to the ferries and continue their untrammelled journeys. Surprisingly the Orient Express only gave up stopping in Folkestone in 2008 – the year of the first Triennial – but channel ferries had long since given up landing and departing. The demise of cross-channel operations, including hovercraft traffic, followed as a combined consequence of the Euro Tunnel’s inauguration – whose construction had at least provided much local employment while it lasted in the 1980s and 1990s – and the fact of the far larger port of Dover a few miles east being able to operate a 24-hour ferry service, since, unlike Folkestone, its harbour was not tidal.

By the advent of the millennium Folkestone had evidently lost a clear sense of its purpose and identity as a place to live, let alone visit. Many of the buildings in the central area surrounding Payers Park, above all on the main arteries of Tontine Street, which leads down to the harbour front, and the cobbled Old High Street, were dilapidated and boarded up. Local unemployment was high, with key industries, services and businesses in the town having gone to the wall. Educational achievement was statistically of the lowest standard in the country, which pointed to bleak post-school prospects for young people regardless of whether or not they chose to remain in the town. As Schlieker reported on the occasion of the first Triennial in 2008:

Folkestone Harvey Central ward, which is the focus for the Creative Quarter and much of the Triennial, is ranked worst in Kent for health deprivation and worst in the south-east (out of 5,139 wards) for employment, putting it in the bottom 0.4 per cent nationally. East Folkestone has 40 per cent unfit housing (overcrowding, damp, lack of basic facilities). In 2003 o...