I.1

Introduction

Exploration of the Research Topic

The main research question we address is how to understand and influence long-term and complex socio-technical transitions. Our journey in this part of the book is geared to developing a socio-technical perspective on transitions, borrowing insights from disciplines such as science and technology studies, evolutionary economics and sociology. We define such transitions as shifts from one socio-technical system to another. These systems operate at the level of societal domains or functions such as transport, energy, housing, agriculture and food, communication, and health care. The study of transitions is a special kind of research topic, different from many other topics commonly dealt with in mainstream social science. We consider transitions as having the following characteristics:

1. Transitions are co-evolution processes that require multiple changes in socio-technical systems or configurations. Transitions involve both the development of technical innovations (generation of novelties through new knowledge, science, artifacts, and industries) and their use (selection, adoption) in societal application domains. This use includes the immediate adoption and selection by consumers (markets and integration into user practices), as well as the broader process of societal embedding of (new) technologies (e.g. regulations, markets, infrastructures, and cultural symbols).

2. Transitions are multi-actor processes, which entail interactions between social groups such as businesses or firms, different types of user groups, scientific communities, policymakers, social movements, and special interest groups.

3. Transitions are radical shifts from one system or configuration to another. The term “radical” refers to the scope of change, not to its speed. Radical innovations may be sudden and lead to creative destruction, but they can also be slow or proceed in a step-wise fashion.

4. Transitions are long-term processes (40 –50 years); while breakthroughs may be relatively fast (e.g. 10 years), the preceding innovation journeys through which new socio-technical systems gradually emerge usually take much longer (20–30 years).

5. Transitions are macroscopic. The level of analysis is that of “organizational fields”:

Our analysis thus focuses on a particular level of organizational hierarchies, which are often thought to consist of the following levels: individual, organizational subsystem, organization, organizational population, organizational field, society, and world system. Our focus thus exceeds the level of businesses or firms and populations (e.g. industries), but it is more specific than the level of societies or world systems. Organizational fields, which consist of communities of interacting populations, receive increasing attention in organization studies and sociology (e.g. Leblebici et al., 1991; Davis and Marquis, 2005; Meyer et al., 2005). Our study of transitions contributes to this new stream of research, albeit with a stronger focus on socio-technical change and innovation.

Transition is not just an unusual research topic; our approach to it, marked by zooming in on technology, is also quite specific. This choice should not be confused with an approach that focuses on the material (hardware) aspects of transitions only. Our socio-technical perspective is based on a contextual understanding of technology. Building on science and technology studies (STS), we understand the development of technology as “heterogeneous engineering” (Latour, 1987; Law, 1987). This involves not only the development of knowledge and prototypes, but also the mobilization of resources, the creation of social networks (e.g. sponsors, potential users, firms), the development of visions which may attract attention, the construction of markets, and new regulatory frameworks. Technological development thus involves the creation of linkages between heterogeneous elements. In this respect, Hughes (1986) coined the useful metaphor of building a “seamless web,” indicating that technological change requires actors to combine physical artifacts, organizations (e.g. manufacturing firms, investment banks, and research and development laboratories), natural resources, scientific elements (e.g. books and articles), and legislative artifacts (e.g. laws). In a similar vein, Rip and Kemp (1998) have defined technology as “configuration that works.” While the term “configuration” refers to the alignment between a heterogeneous set of elements, the addition “that works” suggests the configuration should stabilize in “fulfilling a function.” These definitions of technology emphasize not only the inherent connections between technical and social aspects, but also the intrinsic orientation towards use and functional application domains. Technologies are always “technologies-in-context” (Rammert, 1997: 176). Our perspective, then, is decidedly socio-technical.

The focus on technology and innovation is important for a study of transitions because since the nineteenth century technology has been used by many actors as a way of advancing the modernization process (Schot, 2003). Technological change has assumed an incessant, endogenous, innovative dynamic in modern, capitalist societies. This does not mean, however, that new knowledge and artifact designs are prime movers in transition processes. We are obviously not technological determinists. Rather, our argument is that actors in transition processes give technology a prominent role in their change strategy (see for example Giddens, 2009; Chapter 6). Technology is a site for organizing change. This tendency is also clearly visible in the present discussion on transitions towards sustainability. Some claim that the emphasis on technological solutions is part of the problem, arguing that real solutions for sustainable development should come from social or cultural change. In our socio-technical approach, however, we study how material, social and cultural changes interact in transitions towards sustainable development.

Another important characteristic of our research question is its deeply historical nature. Therefore, it is useful to explore the specific characteristics of historical change and its explanations, which may differ from other types of explanations current in the social sciences. In Chapter 6 we will elaborate on this issue in depth. In this part our focus is only on the identification of relevant heuristics or criteria for theory development regarding long-term change processes. To this end, we first delve into theories of history. Specifically, we present three types of heuristics.

First, historians underscore the importance of co-evolution between ongoing processes and lateral thinking. They share a conviction that a sense of the whole must inform the understanding of the parts:

In the context of this lateral competence, Freeman (2004: 548) quotes Schumpeter about the importance of history for theory development on technological innovation:

A second cluster of heuristics relates to issues of explanation and causality, for instance, notions about multi-causality, anti-reductionism, search for patterns, and the importance of context:

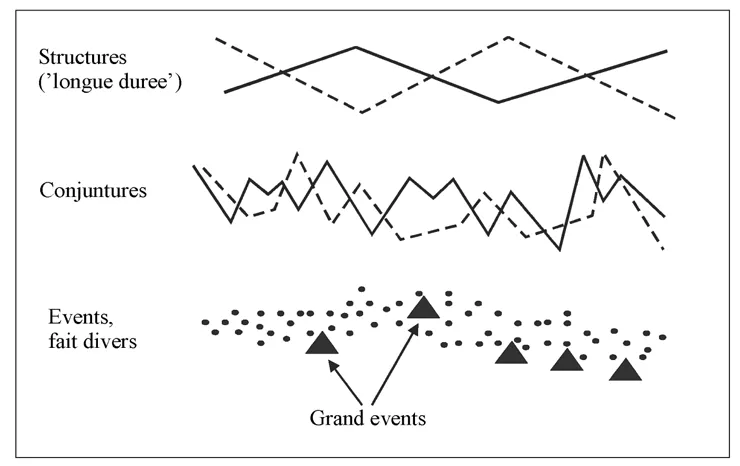

Third, historians have learned to distinguish between different types of chronologies. Braudel (1958; 1976) identified three types based on different time scales and different speeds: a) structural history, associated with the study of geological, geographic, social, and mental structures that change only glacially; b) conjunctural history, associated with the study of economic and demographic cycles with durations of decades rather than centuries; and c) eventful history, associated with the ephemera of politics and events reported in newspapers (Figure I.1.1).

We believe any theory of transition should incorporate Braudel’s ideas of multiple time scales, while acknowledging that his perspective was topdown and structuralist by conceptualizing agency (events) as superficial disturbance of structural changes. Furthermore, Braudel never explicitly theorized the relationships between his levels.

In sum, theories of history offer the following useful general heuristics for studying long-term processes: multi-causality, co-evolution, lateral thinking, anti-reductionism, patterns, context and the use of different time scales. In the following chapters, these heuristics inform our conceptual work on long-term socio-technical transitions.

History is also important for transitions research in another way, however. We will not only develop a socio-technical perspective on transitions, but also test the plausibility of the proposed perspective with historical case studies. In our argument we rely on historical case studies for three reasons. First, studies of future transitions cannot be tested as of yet (because the future still lies ahead), while studies of present or ongoing transitions are also limited, because they cannot cover entire transitions from beginning to end. Second, as we will argue in Chapter I.6, testing requires the tracing and analysis of processes, event sequences, and agency; the historical case-study method is well suited for this. Third, history is important as a treasure trove of empirical case studies that enable what Yin (1994) has called analytical generalization towards conceptual perspectives and theories. This is exactly how we will use our case studies, especially in Chapter I.4 where multiple cases are used to replicate the basic perspective, as well as to further refine it (we will distinguish different analytical transition pathways).

We develop our argument as follows. Chapter I.2 introduces the so-called multilevel perspective (MLP) on transition. Subsequently, in Chapter I.3 we elaborate on the theoretical foundations of this perspective. We position it as a specific crossover between science and technology studies (STS), evolutionary economics, and sociology. In Chapter 4 we further differentiate the MLP, and show how particular types and sequences of interactions lead to different transition pathways. We propose four transition paths, provide empirical illustrations (which are necessarily short), and provide a future research agenda. Chapter I.5 discusses empirical findings and conceptual elaborations of Strategic Niche Management (SNM). This is a specific management approach embedded not only in new ways of thinking about governance (for this argument see Part III), but also in the MLP as it is grounded in a combination of STS, evolutionary economics, and sociology. Finally, in Chapter I.6 we reflect on the nature of the explanations provided by the MLP.

Our choice to focus on MLP excludes a number of other socio-technical approaches which could be mobilized to advance our understanding of transitions. In particular we would like to point to the so-called functional perspective on technological innovation systems (TIS approach) which emphasizes how innovation systems work, instead of how they are structured, as is the case for original innovation systems literatures (for this point and a comparison between MLP and TIS, see Markard and Truffer, 2008; see also Geels et al., 2008). In the TIS approach the overall system function is the generation, diffusion and use of innovations. Subsequently, several sub-functions can be recognized, ...