Perversion and Modern Japan

Psychoanalysis, Literature, Culture

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Perversion and Modern Japan

Psychoanalysis, Literature, Culture

About this book

How did nerves and neuroses take the place of ghosts and spirits in Meiji Japan? How does Natsume Soseki's canonical novel Kokoro pervert the Freudian teleology of sexual development? What do we make of Jacques Lacan's infamous claim that because of the nature of their language the Japanese people were unanalyzable? And how are we to understand the re-awakening of collective memory occasioned by the sudden appearance of a Japanese Imperial soldier stumbling out of the jungle in Guam in 1972?

In addressing these and other questions, the essays collected here theorize the relation of unconscious fantasy and perversion to discourses of nation, identity, and history in Japan. Against a tradition that claims that Freud's method, as a Western discourse, makes a bad 'fit'with Japan, this volume argues that psychoanalytic reading offers valuable insights into the ways in which 'Japan' itself continues to function as a psychic object.

By reading a variety of cultural productions as symptomatic elaborations of unconscious and symbolic processes rather than as indexes to cultural truths, the authors combat the truisms of modernization theory and the seductive pull of culturalism. This volume also offers a much needed psychoanalytic alternative to the area studies convention that reads narratives of all sorts as "windows" offering insights into a fetishized Japanese culture. As such, it will be of huge interest to students and scholars of Japanese literature, history, culture, and psychoanalysis more generally.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

Introduction

Notes

1

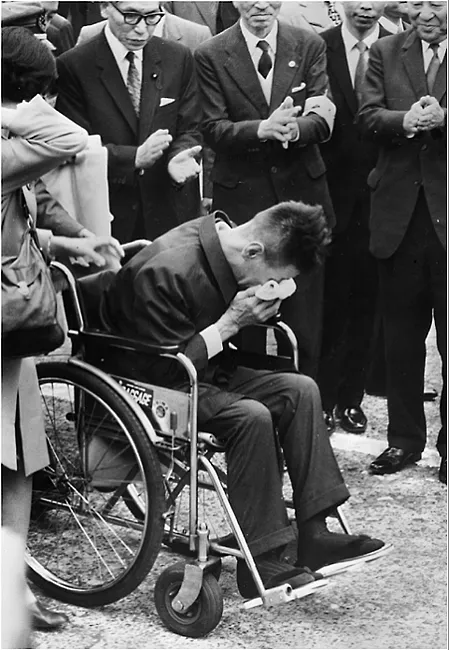

Speculations of murder

Yokoi a murderer

Table of contents

- Perversion and Modern Japan: Psychoanalysis, Literature, Culture

- Contents

- Figures

- Contributors

- Introduction

- 1 Introduction

- 1 Speculations of murder

- 2 Introduction

- 2 Japan’s lost decade and its two recoveries

- 3 Introduction

- 3 The corporeal principles of the national polity

- 4 Introduction

- 4 Pelluses/phani

- 5 Introduction

- 5 Penisular cartography

- 6 Introduction

- 6 Two ways to play fort-da

- 7 Introduction

- 7 The double scission of Mishima Yukio

- 8 Introduction

- 8 Navigating the inner sea

- 9 Introduction

- 9 In the flesh

- 10 Introduction

- 10 Sexuality and narrative in Sōseki’s Kokoro

- 11 Introduction

- 11 Exhausted by their battles with the world

- 12 Introduction

- 12 Freud, Lacan and Japan1

- 13 Introduction

- 13 Packaging desires

- References

- Index