1

The constraints-based approach to motor learning

Implications for a non-linear pedagogy in sport and physical education

Keith Davids

Introduction

Recently, a constraints-led approach has been promoted as a framework for understanding how children and adults acquire movement skills for sport and exercise (see Davids et al., 2008; Araújo et al., 2004). The aim of a constraints-led approach is to identify the nature of interacting constraints that influence skill acquisition in learners. In this chapter the main theoretical ideas behind a constraints-led approach are outlined to assist practical applications by sports practitioners and physical educators in a non-linear pedagogy (see Chow et al., 2006, 2007). To achieve this goal, this chapter examines implications for some of the typical challenges facing sport pedagogists and physical educators in the design of learning programmes.

The theoretical basis of a constraints-led approach

A systems-oriented perspective, informed by ideas from dynamical systems theory, the complexity sciences and ecological psychology, conceptualizes humans as complex, neurobiological systems that exhibit several fundamental properties (Davids et al., 2008). These include:

1 composition of many independent degrees of freedom and different interacting levels in the system (e.g. neural, hormonal, biomechanical, psychological levels);

2 inherent pattern-forming tendencies which can emerge as system components (e.g. muscles, joints, limb segments), and spontaneously co-adjust and co-adapt to each other;

3 openness to constraints (e.g. information that can regulate actions);

4 capacity of complex systems to exhibit tendencies towards stability and instability;

5 the potential for non-linearities in behaviours emerging from the system exemplified by small skips, jumps and regressions in motor learning.

Research has shown that neurobiological systems are able to exploit the constraints that surround them in order to allow functional patterns of behaviour to emerge in specific performance contexts. They tend to settle into stable patterns of organization (behaviours) because of intrinsic self-organization processes. A neurobiological system’s “openness” to energy flows allows them to use that energy as informational constraints on their behaviour. These ideas show that the type of order that emerges in neurobiological systems is dependent on initial conditions (existing environmental conditions) and the range of constraints that shape their behaviour.

Constraints and movement co-ordination

The key idea of pattern formation under constraints in complex neurobiological systems is most useful for physical educators and sport pedagogists. Pattern form-ing dynamics emerge under interacting constraints in neurobiological systems by harnessing the body’s mechanical degrees of freedom during learning. Bernstein (1967) argued that the acquisition of movement co-ordination was “the process of mastering redundant degrees of freedom” (p.127), or the conversion of the human movement apparatus to a more controllable, stable system.

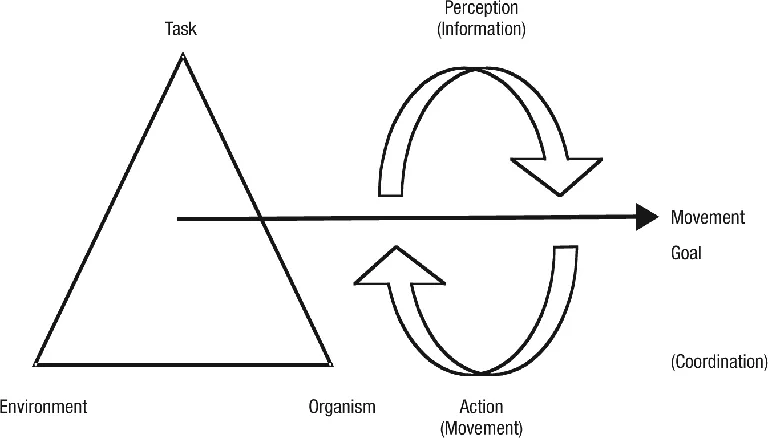

The constraints-led approach views influential factors within the learning environment as constraints that guide the acquisition of movement co-ordination and control (Newell et al., 2003). According to Newell (1986), constraints can be classified into three distinct categories to provide a coherent framework for understanding how co-ordination patterns emerge during goal-directed behaviour (see Figure 1.1).

1 Organismic constraints refer to characteristics of individual performers, such as genes, height, weight, muscle–fat ratios, and connective strength of synapses in the brain, cognitions, motivations and emotions. These unique characteristics represent resources that can be used to solve movement problems or limitations that can lead to individual-specific adaptations by a performer. Newell’s (1985) model of motor learning captures how Bernstein’s (1967) degrees of freedom problem can help elucidate the distinction between performers of different skill levels. Early in learning, novices at the “co-ordination” stage are challenged with harnessing available motor system degrees of freedom to complete a task. At this stage a functional co-ordination pattern is assembled to achieve the task to a basic level. However, if environmental conditions change, the basic pattern may need to be adapted. This is the next challenge for learners as they explore how to adapt an action to different performance conditions. Performers who can flexibly adapt a stable co-ordination pattern for use in changing performance environments are at the “control” stage of learning. Finally, expert performers reach the “skill” stage when they can vary the degrees of freedom used in a co-ordination pattern in an energy-efficient, creative manner to fit changing circumstances in dynamic environments (Newell, 1985; Davids et al., 2008).

2 Environmental constraints can be physical in nature, such as ambient light or temperature. Gravity is a key environmental constraint on movement coordination in all tasks, as experienced by all athletes including skiers, divers, gymnasts and ice skaters. Some environmental constraints are social rather than physical. Spectators provide an influential environmental social constraint for learners and more experienced athletes during sport performance.

3 Task constraints are usually more specific to particular performance contexts than environmental constraints and include specific performance goals, rules of a specific sport, equipment and implements to use during a physical activity, performance surfaces and boundary markings. The functional movement patterns of an individual performer may vary, even within seemingly highly consistent activities such as a gymnastic vault, a long jump approach run or a golf swing, because the task constraints differ from performance to performance. A significant task constraint is the information available in specific performance contexts that athletes can use to regulate their actions.

Information constraints on action

James Gibson (1979) argued that neurobiological systems are surrounded by huge arrays of energy flows, which can act as information sources (e.g. optical, acoustic, proprioceptive) to support decision-making, planning and movement organization, during goal-directed activity. For example, informational constraints can be used to continuously guide actions as a player navigates through a defensive formation in a rugby union field. Gibson’s ideas imply that pedagogists need to understand the nature of the information that regulates movement (i.e. “what” information). The structure of energy in the surrounding arrays carries information for a performer that is specific to certain contexts and that is available to be directly perceived. For example, light reaches the eyes of a netball player after having been reflected off surfaces (i.e. the ground and the goal posts) and moving objects (i.e. other players and the ball) in the busy, cluttered performance environment. Movements in the performance environment cause changes to energy flows that provide specific information on environmental properties that can be used by individuals as affordances for action (see Kugler & Turvey, 1987). Because flow patterns are specific to particular environmental properties, they can act as invariant information sources to be picked by individual performers to constrain their actions.

Gibson (1979) argued that movement generates information that, in turn, supports further movement, leading to a direct and cyclical relationship between perception and movement. This position was summarized by his statement that “We must perceive in order to move, but we must also move in order to perceive” (p. 223). According to ecological psychology, the use of information to support movement requires a law of control that continually relates the current state of the individual to the current state of the environment. That is, a law of control relates the kinetic property of a movement to the kinematic property of the perceptual flow (Warren, 1990).

The implication of these ideas is that, in sport, learners need to acquire specific information-movement couplings, which they can use to support their actions. They achieve this process by becoming attuned to relevant properties that produce unique patterns of information flows in specific environments (e.g. different sport contexts). Jacobs and Michaels (2002) argued that there are two processes involved when learners enhance their attunement to information for action. First, learners educate attention by becoming better at detecting the key information variables that specify movements from the myriad of variables that do not. During practice they narrow down the minimal information needed to regulate movement from the enormous amount available in the environment. Second, learners calibrate actions by tuning movement to a critical information source and, through practice, establish and sustain information-movement couplings to regulate behaviour.

From a constraints-led approach there are a number of principles that can guide the design of learning environments. These principles have been captured in a non-linear pedagogical framework (Chow et al., 2006). In the remaining sections of this chapter, we will focus on how pedagogists might manipulate information to constrain the emergence of functional movement patterns in learners and how they might design learning environments so that decision-making behaviour can emerge from the constraints of practice. In this design approach the interaction of the main classes of constraints on learners during sport performance and physical activity results in the emergence of functional states of movement coordination.

Learning design and informational constraints on action: implications for a non-linear pedagogy

The mutual interdependence of perceptual and action systems suggests that these processes should not be separated in practice tasks by coaches and physical educators. The idea of designing learning environments that couple key sources of information together with specific movements has been supported in previous research on dynamic interceptive actions such as the table tennis forehand drive (Bootsma, 1989) and volleyball serving (Davids et al., 2001). Research on volleyball serving showed that, for the visual flow information from the dropping ball to constrain the initiation of the striking movement, the task should not be decomposed during practice so that the ball toss is decoupled from the strike phase. The traditional pedagogical strategy of breaking up the serving action into the toss and hit components, for separate practice, may reduce attentional demands on the learner. However, it also decouples the ball placement phase from the ball contact phase of the action and disrupts the development of key information-coupling for performing such a self-paced extrinsic timing task. Practising both phases of the serve together without decoupling them permits the learner to explore an emerging relationship between informational and task constraints.

The principle of information-movement coupling proposes that learning design of interceptive actions should involve the process of tasksimplification, rather than traditional methods of part-task decomposition and adaptive training (Davids et al., 2008). Task simplification refers to a process whereby scaled-down versions of tasks are created in practice and performed by learners to simplify the process of information pick-up and coupling to movement patterns. In these scaled-down tasks, important information-movement links are maintained in practice and are not disrupted in practice task design. For example, evidence shows that long-jumpers use information-movement couplings to regulate the stride pattern towards the take-off board during the run-up (e.g. Montagne et al., 2000). The pedagogical implication of this finding is that the run-up and jump phases should not be practiced separately. Rather task simplification could involve novices starting a few strides from the board and learning to ...