1

Tourism and India

An ambivalent relationship

Introduction

India currently stands on the threshold of becoming a major world power. Like Brazil, Russia and China, India has been recognised as playing a crucial role in the future of the world economy. Moreover, globally, tourism has become of central importance to social, cultural and economic lives in the twenty-first century. However, unlike these other countries, India has not been able to harness tourism development to the same extent. Indeed, as a country, India has always had a rather uneasy and ambivalent relationship with tourism. This book thus details the significance of the practices of tourism for India in the twenty-first century. The overarching aim of the book is to help you reach a point of critical understanding about tourism and India rather than for us to simplistically describe the many, various sites of tourism in India. We spent a lot of time pondering the title for this book, and we want to emphasise that it is about tourism and India and not just about tourism in India. This introduction is thus intended not only to welcome you to our book but also to outline the position from which we have written it – the position of the contemporary critical tourism studies literature – we hope in an accessible, readable and enjoyable way. More crucially, however, we wish to present you with a reading experience that will challenge some of your own preconceptions about tourism and India. Although we have divided the book into discrete chapters (to aid reading) we are also cognisant of the ways in which tourism as a cultural activity blurs with or fades into other aspects of contemporary social, cultural, economic and environmental experiences. Moreover, we are also acutely aware of the underlying power relations in tourism production and consumption, as well as how these structures are sometimes transgressed and subverted in the Indian context. We believe that the study of tourism is a vibrant, innovative and interesting academic subject, though you would hardly know so from reading some of the introductory textbooks on tourism and India with their rather bland definitions and descriptions of tourism. Although Branding India (2009), the recent account of India’s successful ‘Incredible India’ campaign by Amitabh Kant, the former secretary of India’s Ministry of Tourism, is a more positive contribution to these debates, it is still a rather uncritical and polemical account aimed at furthering the tourism business in India.

Our philosophical approach

We wish to start (and indeed finish) from the perspective that the study of tourism is always difficult and contested. In this context, then, we are acutely aware that the world we live in is fast changing and full of transformations – and India as a country is arguably in the fast lane of these contemporary changes. Thus, this book should be thought of not as the definitive answer to students’ questions about tourism and India, but rather as a starting point for an ongoing shared project. Our account of tourism and India draws upon many aspects of post-colonial and post-structuralist philosophy, not because it may be fashionable but because we do find it helps us to understand contemporary tourism and India as a set of complex, negotiated, contingent, blurred and incomplete practices and ideas. We also draw upon the politicised aspects of tourism and tourism development in order to explain the conflicts that frequently arise in India over tourism. Indeed, as Dann (1999: 27) has argued, ‘unless issues are problematised – unless we acknowledge that our understanding is incomplete – we will never adequately address issues of tourism development’. We argue that by taking a more sophisticated theoretical approach to the study of tourism and India we may actually hear better the voices of people involved in the practices and processes of tourism development and management.

Moreover, because tourism is integral to processes of globalisation both as an outcome and as a contributing factor, any analysis of tourism needs to take account of theoretical advances in the study of the processes of globalisation. We thus need to understand India in a global context of competing destinations, each of which is trying to position itself with unique selling points. Indeed, it may also be better to think of multiple ‘Indias’ in this context with a multitude of competing destinations (Goa, Rajasthan, Kerala, Assam, Kashmir) under the ‘India’ umbrella and with multiple unique selling points. On the other hand, however, processes of globalisation have also led to a degree of homogenisation taking place whereby places become much more similar as a result of the progress of multinational companies selling international brands (fast food outlets are now widespread in India) and international popular culture for international tourists. Nevertheless, we would argue that India retains a remarkable degree of differentiation despite the homogenising processes of globalisation. Many international tourists in India revel both in the exotic and in the everyday and are in search of a series of ‘experiences’ however imagined.

In this book we are also acutely interested in the behaviour of tourists who visit India themselves. However, our understanding of ‘behaviour’ does not draw upon psychological models that seek to reduce human behaviour to a simple set of attributes; rather we take a more anthropological approach to understanding behaviour as linked to cultural beliefs, habits and meanings. In so doing, we are also aware that the traditional division between tourism, leisure and everyday life is also blurring with the growth of serious leisure (Stebbins, 2007) and so called ‘voluntourism’ (Wearing, 2001).

The globalisation of tourism also involves broader political questions and, importantly, the ownership of power (Hall, 1994). Perhaps, as a result, research into tourism has begun to focus more explicitly upon the concept of power itself. In particular, this has meant a shift from the more basic political and economic concepts of power towards an examination of social and cultural relations of power in tourism (Mowforth and Munt, 1998), with particular reference to Foucauldian notions of power (Cheong and Miller, 2000; Hollinshead, 1999). Cheong and Miller (2000: 378), for example, argue that, ‘power relationships are located in the seemingly non-political business and banter of tourists and guides, in the operation of codes of ethics, in the design and use of guidebooks, and so on’. And clearly we can see this in evidence in India with the Lonely Planet guide exerting a disproportionate effect on many international tourists’ behaviour (see also Chapter 6). In terms of tourism development strategies it is recognised that, in addition to participating in the formulation and implementation of tourism ethics, various gatekeepers and brokers discuss and negotiate how far development should proceed, what type of development is optimal, and who should enter as tourists. As we shall see in Chapter 2, this is very important in the context of India as regimes of governance influence the direction of tourism development.

Throughout this book, then, we are also interested in the interplay between metaphor and materiality in tourism and attempt to show that the ways in which people think about the world have implications for the ways in which they then experience tourism in India. However, we do not think that the very stuff of such experiences can be reduced to a simple reading of the materiality of the environment or landscapes of tourism; rather such experiences are fundamentally mediated by a whole host of contemporary media lenses. Moreover, because of the globalisation of mediascapes those in economic need in countries such as India are acutely aware of the desires of others around the world (Shurmer-Smith and Hannam, 1994). Thus, in what follows in this book we concentrate rather a lot upon these mediatised representations and experiences, drawing upon studies of film, literature and advertising, not just because they give pertinent visual illustrations but also because such examples allow us to appreciate the different ways in which people conceive of tourism practices as constitutive of their own identities. Thus, such mediatisations are not simply representations but are also linked with the material conditions of tourism, which certainly need to be problematised. For example, John Hutnyk’s (1996) remarkable book The Rumour of Calcutta has examined how a combination of tourism representations – literary, photographic, cinematic and cartographic – enframe the tourism experience of Calcutta. Moreover, as we shall see in subsequent chapters, many of these representations of, and in, India rely on ‘exotic’ social constructions that are frequently manifestations of older colonial, imperial and orientalist desires.

A critical, contemporary profile of India

As the discussion of globalisation and tourism above has shown, India is clearly positioned in the twenty-first century to become a major economic power and has variously been described as an ‘emerging giant’ (Panagariya, 2008) or an ‘awakening elephant’ (Kant, 2009). As Panagariya (2008: xv) notes, ‘[a] sure fire way to capture the attention of Indian audiences is to tell them that India is destined for stardom in the twenty-first century’. Hence, in this section we wish to outline the key general features of contemporary India in terms of its geography, politics, economics, sociology, culture and environment.

India is highly varied in terms of its physical geography, from the high mountains of the Himalaya to the tropical southern coastal regions, from the vast central plains to the densely forested north-east. India has a distinct monsoon climate with (usually) hot, wet summers and dry, cooler winters interspersed by two very hot and dry months (May and June). The monsoon rains help to feed India’s vast rivers and thus support India’s agricultural production. The success or failure of the rains can make a huge difference to India’s national income in any given year as well as having a profound effect on the seasonality of India’s international tourism flows, in particular.

India is also a vast, rapidly developing country with a population of 1.1 billion citizens, who speak eighteen official languages, making it the largest functioning democracy in the world. But it is also a country of vast differences across the twenty-eight states and seven union territories that constitute India’s federal system of governance. In terms of economics, India has a gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate in excess of 8 per cent, making it one of the fastest-growing economies in the world. Moreover, India is now much more integrated into the world economy than it was back in the early 1990s and has seen both its exports and its foreign investment multiply in value. Technologically, India has also been transformed in the last twenty years. For example, back in 1991 India had 5 million phone lines; today nearly 600 million Indian people have mobile phones as India’s middle class grows, consumes and isolates itself in its own ‘housing colonies’. Indeed, as we shall see, India’s ‘new middle class’ (Fernandes, 2007) has been crucial in terms of the development of both domestic tourism and outbound tourism (see Chapters 7 and 8 respectively).

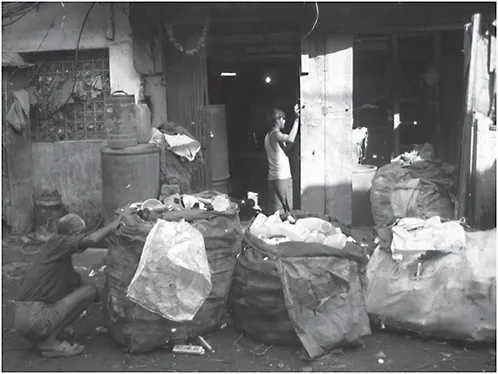

However, against this picture of massive growth and prosperity we also need to note that India still has a great deal of poverty and inequalities (Figure 1.1). Despite an absolute reduction in poverty in recent years, the urban–rural inequalities have worsened. As Panagariya (2008: xxvi) argues: ‘[t]he ultimate development problem India faces is that of transforming its primarily rural, agrarian economy into a modern one’. The vast majority of the Indian population still lives in rural areas and relies on farming for its livelihood. Moreover, outside of agriculture, ‘approximately 90 percent of the workforce remains employed in the informal, unorganized sector’ (Panagariya, 2008: xxvi). In addition, these inequalities have been exacerbated by the failure, in part, of the Indian government to deliver effective access to adequate basic social services such as water, education

and health, despite considerable investment (Dreze and Sen, 1995). Varma (2004) meanwhile has accused India’s new middle class of a growing amnesia towards this deprivation.

Against this backdrop of contemporary prosperity and poverty, we also need to note the uniquely fractured social structure in India and the ways in which this has been politicised in recent years, often violently. Although ostensibly a ‘secular’ country that does not advocate any one religion, India’s population is over 80 per cent Hindu, with Muslim (14 per cent), Christian (2 per cent), Sikh (2 per cent) and other small minorities, according to the 2001 census of India. Moreover, in recent years India has witnessed the rise of Hindu nationalism, which has included ‘state encouraged violence against religious minorities’ (Nanda, 2004: 1). Nanda (2004: 2) further argues that, as India modernises technologically, this has only served to ‘further an equally aggressive cultural re-traditionalization, visible in the growing influence of religious nationalist ideas on the institutions of civil society and the state’. Nevertheless, as Pinney (2001: 1) notes, despite these internal divisions, there are also many places of shared identity, most particularly in th...