![]()

1

‘Amidst the heterogeneous masses’

Household Words and the Great Exhibition of 18511

Ten months before the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations opened in Hyde Park, Richard Horne published an article entitled ‘The Wonders of 1851’ in Charles Dickens’s weekly journal Household Words. In this article, Horne took issue with the debate about which system of classification the Committee of the Great Exhibition should adopt to order the mass of exhibits. There were two obvious choices: one was to sort them according to the different manufacturing processes to which they pertained, the other, to sort them by their place of origin. The former, ‘a fusion of the productions of all nations’, was the order favoured by Prince Albert, because it would ‘amalgamate and fraternise one country with another’.2 Moreover, it would also allow those visitors with a stake in manufacturing to compare different production methods directly.

Horne dryly comments that ‘this feeling is excellent; but we fear it would cause an utter confusion, and amidst the heterogeneous masses, nobody would be able to make a study of the productions of any particular nation’. In his view, ‘the natural arrangement’ would be to keep ‘the productions of each country [ … ] separate’, even at the expense of those visitors whom this industrial Exhibition claimed to benefit the most. Clearly, the need for ordering and containing the heterogeneous masses of nations, cultures, peoples, and classes, and for keeping ‘fraternisation’ between them in check, superseded the advantages that ‘horny-handed industry’ might derive from a direct comparison.3

The debate about classification highlights the key contradictions that riddled both the Exhibition itself and Household Words’ treatment of it. On the one hand, the Exhibition was publicised as a fair of universal harmony transcending national, social, geographical, religious, gender, and racial boundaries. On the other, it represented an arena for direct comparison and even competition between these. Precisely because the Exhibition aimed to ‘fraternise’ nations and thus posed a threat to national boundaries and the safeties that they suggested, it also provoked jingoistic responses. The same ambiguity is evident in terms of class: even while the Great Exhibition claimed to celebrate the ‘dignity

of labour’4, it excluded labourers both from the exhibits themselves and from its implied audience.

This chapter argues that, rather than delivering a faithful representation of ‘all nations’, the Great Exhibition represented the psychological map of the world as it lived in the collective imagination of Victorian England. I will examine briefly who created the Great Exhibition’s vision of the world, and who came to view it. I will then sketch what this vision looked like, particularly with reference to India and China, before turning to Household Words’ stance on the Exhibition and its surrounding questions of nationality and national character.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT AND CONTEMPORARY RECEPTION

The Great Exhibition took place soon after the troubled ‘Hungry Forties’ and within only three years of the European revolutions of 1848 and Chartist disquiet in Britain. These recent experiences lingered in the public memory and found expression in pessimistic predictions that the Exhibition would invite a Chartist rebellion or foreign invasion. When it turned out to be a peaceful event, many commentators expressed their exuberant hopes that it would ring in an ‘era of peace and good will, of progress and amelioration’.5 Indeed, many studies of the mid-Victorian years, understanding W.L. Burn’s appellation of the ‘Age of Equipoise’ to mean a time of peace, prosperity, and stability, take the Exhibition as their starting point.6 The Exhibition offered such an enormous ‘heterogeneous mass’ of material and meanings that it could be harnessed to almost any conviction or cause: ‘All sorts of morals grow out of [the Exhibition] [ … ] The only fault we have to find with them is, that they cut each other’s throats’, Punch stated the case in a nutshell.7 Recent works on the Great Exhibition, for instance, examine it in terms of commodity culture and consumerism, nationhood, empire, class, and gender.8

The Great Exhibition originally sprang from a series of national exhibitions organised by the Royal Society of Art from 1845 onwards. Their purpose was to ‘improve general taste’ in the design of ‘useful objects’.9 From this emerged the idea of a large-scale exhibition of industry, which was to take place in 1851. The body ultimately in charge of planning it was a group consisting of twenty-four men:

In some ways, they represented a cross-section of society, including members of ‘the aristocracy, the political establishment, science, industry, the arts, commerce and finance, agriculture, and the empire’. Only a quarter of the Royal Commission actually took an active role in organising the exhibition, which ‘suggests that what many of them symbolized [ … ] was more important [than] what they actually contributed’. However, there were also exclusions: while Scotland had one representative, Ireland and Wales had none. Neither did the working classes, ‘because anyone who could claim to speak for them [ … ] would probably have been seen as too radical, democratic, and threatening’.11 This fear later recurred in the pessimistic expectations of unrest and rebellion on the shilling days, a legacy of Chartism and the 1848 European revolutions.

In order to counteract the omission of the working classes, Prince Albert and Henry Cole formed the Central Working Classes Committee (CWCC) in 1850, whose aim it was to enable and encourage members of the working class to attend the Exhibition, organise and monitor cheap accommodation, and facilitate orientation. The CWCC enlisted a number of famous names, such as Charles Dickens, Samuel Wilberforce (the Bishop of Oxford who had coined the phrase ‘dignity of labour’), Arnold Thackeray12, and John Forster. Furthermore, it featured ‘several Protestant clergymen, four Members of Parliament, and three former Chartists [ … ] Given the elite composition of the Royal Commission, the CWCC must have appeared quite radical’.13 Consequently, when the CWCC asked for the Royal Commission’s approval of its work, it received a blanket rejection. At the proposal of Charles Dickens, ‘the CWCC dissolved itself after being in existence for barely one month’, since ‘without official recognition, [it … ] would be unable either to render efficiently the services it sought to perform or to command the confidence of the working classes’.14 The reins of the Great Exhibition were thus very much in the hands of the elite, a group of powerful, wealthy men, some of whom had not only an ideological but also a commercial interest in the way in which the Exhibition represented the world.

The Royal Commission’s refusal to acknowledge the Central Working Classes Committee’s work is characteristic of the general emphasis that the Great Exhibition placed on the consuming rather than the producing end of the manufacturing process. In the months leading up to the Exhibition, the fear most persistently voiced was that of a Chartist or foreign rebellion, and the idea of shilling days, on which poorer citizens could enter the Great Exhibition, aroused significant opposition.15 Although the shilling days were intended to make the Great Exhibition accessible and appealing across all sections of society, and to add to its inclusiveness, the responses they evoked in the media and urban, vocal public suggested that they had quite the opposite effect, bringing out the middle classes’ intolerance or, at least, ambivalence.16 Thus, The Times at first reassured its readers that, although the recent European revolutions had made the association of a large crowd of people with revolution inevitable, ‘the unconstrained movements of a free people’ were something to be proud of and look forward to as a manifestation of English liberty.17 Less than three weeks later, before the first shilling day on May 26, The Times stated, with some distaste, its belief that ‘the aristocratic element retires’ before ‘King Mob enters’.18 Similarly, the Illustrated London News expected ‘teeming myriads’ to enter the Crystal Palace on shilling days. Although it reported this in positive terms, there is nonetheless some ambiguity in its voyeuristic attitude to these visitors:

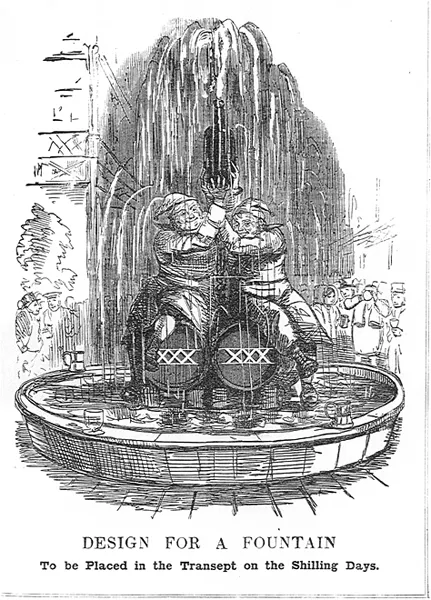

Punch, meanwhile, ridiculed the fear of a drunken mob invading in a cartoon (fig. 3) and decried the decision not to serve alcohol in the Crystal Palace as condescending, since it indicated to foreigners that ‘you poor, uncivilised English could not restrain your appetites [and would] make beasts of yourselves.’ 20

When the behaviour of the attending working classes turned out to be virtually impeccable, this surprising fact provoked much comment and praise in the contemporary press for several weeks, and their habits, manners, and the choices they made in viewing the Exhibition were analysed in detail—yet another curiosity on display inside the Crystal Palace.21 Punch even proclaimed that the humble working classes had shown themselves ‘superior’ to their social betters:

The working-class press, in the form of the Northern Star, hardly paid any attention to the shilling days themselves but registered its disapproval of the ‘aristocratical [sic] hauteur and exclusiveness’ of the opening ceremony on May 1, from which even season-ticket holders were excluded.23 It chafed against ‘the alarmists’, who warned of Socialist and Red Republican violations, and ‘persuade[d] the commissioners to give colour to these dastardly fabrications by the adoption of such a course.’ 24 Simultaneously, however, it offered its regular subscribers a large steel print of the interior of the Crystal Palace as a reward for their custom. These engravings, of which thirty-four appeared in irregular intervals between 1837 and 1851, typically portrayed leaders and supporters of the working classes or important events in the labouring classes’ history. The fact that the last two ever to appear were dedicated to the Great Exhibition indicates the importance that the Northern Star attributed to this event in general.25

The middle classes’ concerns about the inclusion of the workers among the spectators were mirrored by the omission of labour from the spectacle itself. Although the Great Exhibition displayed modern machinery, the worker...