1 Objectives, Scope, and Structure

Not everything in the world that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.

—Albert Einstein

1. PERSPECTIVE

Countries across the globe routinely invest massive resources in transportation infrastructure in the form of new facilities, expansion of existing ones, or maintenance and repair of the network in place. What is common to all of these investments is that they are products of public sector decision making at the local, regional, national, and, at times, international level. Despite their strong technical and economic dimensions, transportation investments represent partial political statements regarding objectives, funding priorities, and targeted service recipients. Viewed from this perspective, transportation investments are similar to other public sector projects. Given this reality, the key questions that this book sets out to explore are normative in nature: What should the objectives and purposes of transportation investments cover? What should their scope be relative to population and space? How should they be analyzed in terms of available analytical tools and the attendant decision making?

Of these, the first question is often the most problematic. The difficulty arises from the fact that like the case of beauty as an objective of art, the purpose of a transportation investment is in the eye of the beholder. Some will argue for transportation-related objectives such as reducing congestion, increasing accessibility, or improving highway safety. Others may argue that equity concerns related to job market access, improved reachability of rural areas, and general spatial mobility should be a project’s leading objectives. Still other arguments pertain to the mitigation of environmental externalities, the impact on urban structure, and the generation of economic growth. Only rarely are political motives cited as the underlying raison d’être for a specific project, although these may very often be the true incentives impelling political decision makers to allocate huge amounts of financial resources to projects that might not have been constructed otherwise. According to this somewhat cynical view, the costs of a project are in effect political benefits to be distributed among constituents, supporters, and functionaries.1

Policy analysts using the tools of their trade might study transportation projects in terms of the key players, their social and economic viewpoints and political agendas, including coalition-building and distributive goals. They might also investigate other stakeholders, such as rent seekers, the administrative bureaucracy, and relationships with other political institutions (e.g., local and federal governments).

While this may be a valid approach to the understanding of how public decision making is conducted, it does not provide a genuine guide—in a normative sense—to which transportation investment alternatives best enhance social welfare. Moreover, several transportation projects are often considered concurrently and under budget constraints that require rationalization, prioritization, and selection. To that end, transportation planning and economic literature provides a set of models and techniques for the analysis of transportation investment projects. The common denominator underlying all of these tools is their goal: ascertaining which alternative investment will yield the highest social return, defined as a combination of transportation, economic, environmental, and social benefits. In following this course, this book regards the enhancement of social welfare, broadly defined, as the prime objective that should guide transportation infrastructure investments policies. (An economically based working definition of social welfare is given in Chapter 3.)

A key distinction should be made here between the concepts project evaluation and project assessment. The former refers to the overall process by which investment alternatives are conceptualized, generated, assessed, ranked, and finally chosen, with economic and noneconomic criteria employed in decision making. The latter concept, (i.e., project assessment), refers to the structured procedure by which the transportation-economic worthiness of each planning alternative is determined. Such assessments are indeed part of project evaluation, which also refers to investment policy together with other decision-making components. While a significant part of this book is devoted to the transportation-economic underpinnings of project assessment, it should be clearly understood that this facet is not an end in itself. Rather, we consider the overall process of project evaluation to be the crucial mechanism for selecting a project, sources of funding, and final implementation (Chapter 2 formally examines these issues). Furthermore, since we vigorously believe in transparency and accountability as inherent features of public decision making, we also maintain that the entire process of project evaluation should be based on acceptable rational, systematic, and justifiable principles. These issues are dealt with in Part E of the book.

Returning to project assessment, this book takes the view that the objective of social welfare maximization is best served by the selection of the “best” project from an array of possible transportation investment alternatives. A related tenet is that an assessment’s results should be conveyed to decision makers by highlighting the fundamental issue of optimal allocation of scarce societal resources, namely, the opportunity costs associated with the forgone investment alternatives. Therefore, with respect to project assessment, the book’s focus is on methods, techniques, and their underlying theories, all aimed at identifying the project that will yield the greatest welfare contribution.

As to project evaluation, the perspective taken in this book states that decisions on the selection and implementation of transportation investment projects are ultimately based on myriad considerations, including economic, planning, engineering, social, environmental, legal, institutional, and political interests. While each of these factors is important in itself and requires a focused analysis, as is the case when deciding other policy matters, the “whole is more than the sum of its parts”. Hence, it would be wrong to assume that project choice decisions are based only on one or a subset of these key considerations. We argue here that all these factors should enter the overall decision process, subject to the fundamental requirement that they be transparent. The structure of decision making, which represents a crucial part of the overall evaluation process, should therefore be transparent as well.

2. APPROACHES TO TRANSPORTATION PROJECT EVALUATION

We can study the process of infrastructure project evaluation from several alternative viewpoints. For instance, the process can be examined from a “positive” perspective, implying that we study how the process actually unfolds. Alternatively, we can study it from a “normative” perspective, where theoretically derived rules are utilized to establish how the process should be carried out. Still another approach entails employment of “policy analysis” tools in order to portray the decision-making process that led to a specific project’s selection.

The distinction between positive and normative analysis, two seemingly polar approaches, is somewhat contrived. A normative analysis aimed at developing guiding principles for project assessment cannot be carried out independently of the parameters set by a positive analysis. That is, a project’s spatial and institutional boundaries provide the framework for its normative analysis regarding the range and distribution of its transportation and nontransportation impacts. Similarly, the required discount rate, the value of time-by-trip type, or the time span of a particular project’s implementation provides inputs for the normative analysis. Alternatively, a positive analysis must employ methodologies that are based on theoretical assumptions guiding the users’ behavior and objectives (e.g., utility maximization) and market structure (e.g., equilibrium market share of various travel modes).

The policy analysis approach is applied to project evaluation in order to characterize the decision making behind project prioritization. To do so, various inputs must be obtained from positive and normative analyses: benefit-to-cost ratios, sources of funding, and the distribution of benefits and costs among socioeconomic groups. A corollary to this observation states that a positive or normative analysis cannot provide relevant information if it does not consider elements of policy analysis such as the weights that various stakeholders and decision makers attach to each type of project impact.

Recognizing these critical interdependencies, this book delves into the key elements from the three major approaches. Part B therefore provides a normative welfare-maximization approach to project assessment. Parts B, C, and D employ a mix of positive and normative approaches to examine assessment principles and techniques of transportation investment projects. Based on these results, Part E develops a policy analysis evaluation approach to the ranking and selection of projects from a large set of alternatives.

3. TRANSPORTATION PROJECT EVALUATION: WHAT INTERESTS US?

The term “transportation project evaluation” is commonly used to describe a formal procedure for ascertaining the net societal welfare contribution found among several specific investment alternatives that may differ in nature (e.g., mode), goals, and incidence of benefits and costs. While societal welfare gains need to be formally defined (see Part B), here we will deal with the application of project evaluation at four levels of transportation planning.

A. Comprehensive Transportation Plan

Sometimes called “a transportation master plan,” its main function is to map the full range of transportation issues and needs located within a given geographical area and to subsequently propose a range of transportation developmental options. As such, this plan should be part of a larger comprehensive land-use plan that defines urban and regional objectives as well as articulates the planners’ and community’s views about the region’s future spatial structure. Both plans must be compatible with land-use and population policies as well as harmonized in a dynamic way so that the recommended transportation investments will support larger regional growth and social objectives. The land-use segment of the plan should also facilitate execution of the transportation plan with respect to eminent domain rights-of-way and generation of the critical demand necessary to rationalize the transportation investment. In brief, the comprehensive transportation plan acts as a guidebook from which more specified plans could be derived.

Given the nature of the comprehensive transportation plan, the evaluation process focuses on its compatibility with the comprehensive land-use plan and how well the region’s economic, social and environmental objectives are supported by the plan. From a normative perspective, comprehensive transportation plans should be rationalized and updated periodically even if not statutorily required. This recommendation is rarely complied with. In practice, the most appropriate time to do so is the period following a national census, when new population and travel data and trends can be extrapolated.

B. Transportation Development Plan

A transportation development plan’s declared aim is to provide the legal, economic, and planning guidelines for implementing the transportation options derived from the comprehensive plan. Of special concern are statutory issues, planning components such as phasing and readiness for implementation, and acquisition of right-of-way. Evaluations of transportation development plans focus mainly on their ability to promote project implementation within 10–15 years time horizon.

C. Transportation Investment Plan

Also called a “strategic plan” or a “comprehensive investment plan,” it represents a package or set of projects that are likely to be implemented in the medium- to long-term. The key objective of a strategic plan is to provide a framework for measuring and prioritizing a set of specific transportation investment projects for the purpose of determining an adequate schedule or implementation sequence. Since transportation projects can be technically and spatially interdependent within a region, it is necessary to determine the optimal set of plans that will maximize social welfare given expected budget, statutory, and planning constraints. A strategic plan likewise needs to show the value of an alternative set of projects in light of strategic policy options as well as a range of future travel growth rates (Nash, 1993). Evaluations of such plans are suitable for only 4 to 5 years because beyond this period, key conditions—primarily financial resources availabilities—are likely to change.

D. Specific Investment Projects

The key objective of plan evaluation is to determine the welfare contribution of a specific project relative to a set of planning alternatives, including the so-called “do-nothing” or “do-minimum” alternative. Economic measures, such as benefit-to-cost ratios, are the key criteria applied to these plans provided that statutory, planning, and right-of-way conditions will be met.

This book deals mainly with evaluation of specific transportation investment projects even though analyses of specific plans and strategic plans are highly related due to their common use of the “positive net social welfare” criterion as the key decision principle. Therefore, while issues related to the evaluation of comprehensive or transportation investment plans will be discussed, evaluation of specific investments and their selection from a set of planning alternatives will remain the focus of our attention.

4. STRUCTURE OF BOOK

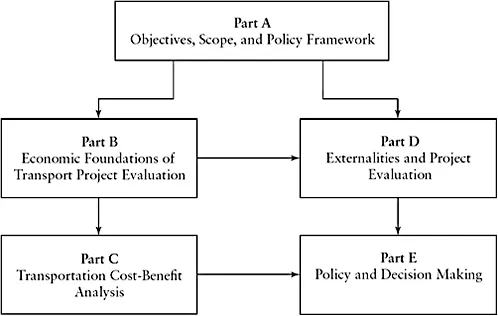

The overall structure of the book is shown in Figure 1.1.

Part A of the book, Objectives, Scope, and Policy Framework, contains two chapters. Chapter 1 presents the book’s overall objectives and scope with respect to project evaluation and choice. Its fundamental canons begin with the view that decision making on transportation investments is, first and foremost, a political statement made within the political arena regarding the allocation of societal resources. The political arena is peopled by multiple interest groups and stakeholders, each with its own agendas, and each vying for the same public resources. Moreover, the decision-making process is carried out within the public sphere, a domain ruled by legal, institutional, bureaucratic, economic, environmental, social, and cultural factors.