2.1 Theories of ‘Illegal’ Migration of Labour

To begin, I want to propose a theoretical framework within which some explanations may be offered for the ‘illegal’ migration of workers to Japan. I do not intend to propound a new sociological theory of migration; instead I want to present the models discussed in Japan. I will then attempt to carefully assess the relevance of these approaches and to identify universal characteristics of labour migration. This discussion will serve to introduce the theoretical concepts and to outline the (surface-)structure of migratory movement directed to Japan. It will provide a background for the Japanese discourse regarding the ‘problem’ of foreign workers.

Since the second half of the 1980s (at latest) there has been an ‘irregular’ migration of labour to Japan—mainly from Asian countries. This gained public attention through coverage by the mass media and political discussion as to whether an official ‘guest worker policy’ should be implemented or not. The term ‘irregular’ indicates that no official recruiting or dispatching of workers was involved, taken, and points to the circumvention of administrative rulings concerning stay and labour. Legally speaking, offences against regulations of the administrative law are committed, thus making applicable such legal descriptions as ‘illegal entrance’ (fuh nykoku), ‘illegal stay’ (fuh zanry), or ‘illegal work’ (fuh shr). However, by use of the term ‘irregular’, the criminal and stigmatizing connotations of ‘illegal’ are avoided. Nevertheless, the ascription of the term ‘illegal’ to the activities and existence of Asian migrant workers is ubiquitous in the Japanese discourse. For that reason, I adopt that label (without meaning to stigmatize cases to which it is applied) when quoting from the literature. In contrast to European countries, the percentage of foreigners in Japan is very small—only 0.8 per cent in a population of approximately 122 million. Koreans constitute 69.3 percent of (registered) foreigners (681,838 of the 984,455 non-Japanese residents). This group is comprised partly of second- and thirdgeneration descendants of those who, after the annexation of Korea as a de facto colony in 1910, immigrated or were deported to Japan as forced labour. The Chinese minority (whose presence dates from the annexation of Taiwan in 1895) comprises roughly 14 per cent of foreigners. Only an estimated 5 per cent of foreigners originate from Western countries (data for 1989 from Yamazaki, 1991:138 and 151). Since Japan first opened itself to foreigners after a period of self-imposed isolation (around 1641 to 1854) it has always pursued a rigid and restrictive ‘foreigner-policy’, with its focus on control still symbolized in the obligation of every foreigner residing for more than three months to carry a ‘certificate of alien registration’.

Except in the case of temporary (coerced) migration from the colonies until the end of the Second World War, the latter regulation —preventing admission of manual labour, and allowing only restricted admission of ‘qualified’ foreigners into clearly circumscribed fields of activity—has remained in force. Since the 1970s, there has been a migration of South East Asian women who are illegally employed in the so-called ‘services’ (that is, in the sex industry). This has been justly described as a traffic in women. The bulk of this immigration is arranged by organized traffickers.

In addition to this influx, there has been since the mid-1980s, larger scale, irregular migration of male ‘working tourists’, although not in the same pattern as recent ‘tourism for work’ (Arbeitstourismus) occurring in such countries as Austria since the opening of borders to former Eastern-bloc countries. In Japan, ‘working tourists’ are forced underground, since distance and financial burden prevent them from re-legalizing their residential status as tourists by first returning to their home country and then re-entering Japan. They therefore remain illegally. This ‘unexpected’ immigration of migrant workers jeopardizes a widely-accepted, semi-ideological view of Japan’s ‘identity’ as a ‘homogeneous island people with little experience in dealing with foreigners’ (see, for example, Komai’s (1992b) speculations as to whether Japan could become a ‘multi-ethnic’ country) and led to an over-heated debate about whether ‘guest workers’ should be welcome, and what sort of legislation would adequately control increasing migration from Asian countries.

2.1.1. The push-pull model

In the literature and public discussion dealing with ‘illegal’ Asian migrant workers, the question was repeatedly posed as to how and why Japan ‘suddenly’ became the target country of an irregular migration of labour. Neo-classical economic explanations gained particular popularity. According to this theoretical approach, labour is seen as a resource which ‘freely’ becomes mobile (or can be mobilized) depending on the supply-demand constellation. Existing disparities are assumed to be balanced through the ‘flow’ of labour. Push- and pull-factors are differentiated, and the attractiveness of labour migration is assessed according to their respective strength. The pull-factors are a cumulative combination of economic, demographic and social developments. For example, they could include falling birth rates, an increasing percentage of elderly (hence a decrease in the working population), and movement of indigenous workers into pleasant, better-paying (that is, white-collar) jobs. The push-factors which cause migrants to leave their countries of origin are overpopulation, pauperism, under-development and unemployment (cf. Castles and Kosack,

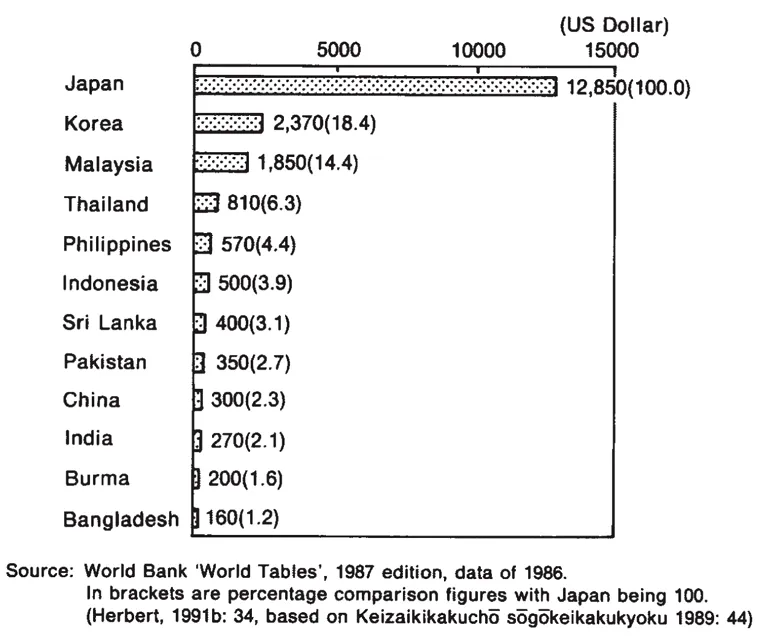

1985:26f.). At the macro-level, exorbitant economic disparities between Japan and its neighbours are evident. Gross national product (GNP) per capita serves as one indicator of disproportion in economic power, as shown in Figure 1. This economic imbalance is regularly mentioned, although not always with such force as here: ‘The premise of international labour migration is always the existence of smaller or bigger economic disparities’ (Miyajima, 1989:10).

At the micro-level, the opportunity to earn a high income in Japan—the result of the enormous wage gap between Japan and its neighbours—lures ‘illegal’ migrants and makes work in Japan attractive for them despite the risk of being repatriated. The prospect of earning money and the expectation of higher wages than at home are the manifest motives most often expressed by migrant workers. However, one should not overlook the possibility that this might be regarded as a legitimatory ascription (from a profit orientation) justifying toleration or shutting of one’s eyes, and for the employers it can help to aid and abet use of ‘illegal’ labour. Moreover, migrant workers are not just ‘profiteers’ who can be portrayed with ‘gold-digger’ metaphors. The decision to migrate is very often made out of the necessity to secure mere survival, and as a last choice, to escape a wretched situation of extreme poverty and unemployment. It can also be claimed that ‘cultural’ motives such as wanting to get to know the ‘success-country’ Japan, or to acquire knowledge and skills, may have been influential in the decision to migrate as is noted in Komai’s (1992a:285) analysis of 115 interviews of migrant workers in Japan.

The push-pull model is the dominant theory in Japan. A representative of the Ministry of Justice borrowed from this theory in enumerating several causes of migration, as he outlined and explained new legal measures and the position of his Ministry at a symposium. The causes mentioned were: economic imbalance (measured by per-capita GNP); revaluation of the yen, which makes migration of labour to Japan more profitable; economic depression in former target-countries of labour migration in the Middle East; worsening labour market conditions in the respective home countries; links between Japan and source countries organized by professional labour agents; and high demand fo...