- 316 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Peirce-Arg Philosophers

About this book

First Published in 1999. The purpose of this series is to provide a contemporary assessment and history of the entire course of philosophical thought. Each book constitutes a detailed, critical introduction to the work of a philosopher of major influence and significance. Many people share the opinion that Charles S.Peirce is a philosophical giant, perhaps the most important philosopher to have emerged in the United States. Most philosophers think of him as the founder of 'pragmatism'. But, curiously, few have read more than two or three of his best-known papers, and these somewhat unrepresentative ones. On reading further, one finds a rich and impressive corpus of writings, containing imaginative and original discussions of a wide range of issues in most areas of philosophy.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

Peirce’s Project: the Pursuit of Truth

I

Logic, Mind and Reality: Early Thoughts

1 Logic and psychology

By 1868, the results of Peirce’s logical and philosophical investigations during the 1860s were in print; the material that was covered in his two series of lectures on the Logic of Science, at Harvard in 1865 and the Lowell Institute the following year, emerged in five technical papers in the Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and in an important and brilliant series of three papers in the Journal of Speculative Philosophy.1 These three papers contain a single unified argument, presenting an account of mind and reality which enabled Peirce, in the third paper, to explain the validity both of deductive reasoning and of ampliative inference. In the course of explaining the possibility of knowledge they introduced many of the pervasive themes in Peirce’s thought; ideas were used which, developed and transformed, were retained throughout the development of his philosophy. So, a survey of these early papers will provide us with an overview of the problems that prompted Peirce’s philosophical work and the sorts of approach to them that he favoured. We shall also be able to understand the difficulties that stimulated the subsequent changes in his doctrines. Therefore, this chapter will offer an account of the arguments and conclusions of the three papers:

‘Questions Concerning Certain Faculties Claimed for Man’ (5.213ff);

‘Some Consequences of Four Incapacities’ (5.264ff);

‘Grounds of Validity of the Laws of Logic: Further Consequences of Four Incapacities’ (5.318ff).

I shall refer to them as QFM, CFI and GVL respectively.

Peirce begins both of the series of lectures by defending the autonomy of logic against those—the ‘Anthropological Logicians’ such as James

Mill and John Stuart Mill—who ‘think that Logic must be founded on a knowledge of human nature and requires a constant reference to human nature’ (CW1 361). As we shall see in the following chapter, this rejection of psychologism—in fact, the denial that any information from the sciences can have a bearing upon logic or epistemology—was a fundamental feature of Peirce’s work; it places him in a common tradition with Frege and much of twentieth-century philosophy. Thus, he would deny the claim of J.S.Mill that the object of Logic was ‘to attempt a correct analysis of the intellectual process called Reasoning or Inference, and of such other mental operations as are intended to facilitate this’ (Mill, 1891, p. 23). However, he did not divorce logic from ‘intellectual processes’ completely, for he claimed that logic was ‘the science whereby we are enabled to test reasons’ (CW1 358). This does not mean, as Mill claimed, that logic is simply ‘a collection of precepts or rules for thinking, grounded on a scientific investigation of the requisites for valid thought’ (Mill, 1868, vol. 2, p. 146). Rather, logic is the ‘classifying science’ which underlies the practice of testing reasons.

if we wish to be able to test arguments, what we have to do is take all the arguments we can find, scrutinize them and put those which are alike in a class by themselves and then examine all those different kinds and learn their properties. (CW1 359)

The ‘formal’ logician, such as Peirce, denies that psychological information is relevant to such classifications; the logician works on the ‘products of thought’ such as linguistically expressed sentences and arguments directly, and has no need to study the ‘constitution of the human mind’.

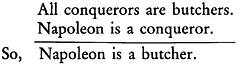

He employs many sorts of arguments to defend this view, and I shall not consider all of them here. A claim that he places some stress upon is that the logical forms shared by arguments that are classified together should not be thought of, primarily, as forms of thought. Consider this printed argument:

|

Peirce insists that this argument has a distinctive form, which anyone can recognize: the logical form is realized in a linguistic object, so it is perverse to think of the form as solely a form of thought (CW1 165). He grants that the linguistic object only has the form it does because it can be understood and thought in a certain way, but holds that that does not make the form any the less a real property of the inscription. The case is parallel to that of colour: no one doubts that the letters in the printed argument are black, yet the concept of blackness ascribes a character to things which they only have ‘in so far and because they can be seen’ (CW1 165).2 It is a real and objective property of the sign that it will affect us in a certain way. Another objection to Peirce’s position stresses, not that such arguments have to be understood by people, but that they are typically produced by human agents. However, this involves a form of the genetic fallacy. Like the ‘tester of reasons’, the flour tester requires a system of classifications to be used in his evaluations of flour samples.

There are many curious and important facts about flour which are of no consequence at all to the inspector of flour. What proportions of the chemical elements enter into the composition of the best flour, whether Nitrogen or Phosphorus should be present in large amounts is of no practical moment to him. (CW1 359)

[All] information as to the forces which produce things of any kind is quite irrelevant to the business of classifying those things. The inspector of flour does not care to know by what agencies wheat grows. (CW1 361)

The logician similarly has no need to take an interest in the production of arguments and the origins of logical concepts. A little later, in an 1869 lecture series on British logicians, Peirce stresses his ‘somewhat singular’ opinion that the question whether an inference is a good one simply concerns the ‘real fact’ of whether, if the premisses are true, the conclusion is also: information about how the inference arises in the mind, or how the argument was produced can have no bearing upon this (R 584—this should be in CW2). The non-psychological approach has other advantages too. It makes it easier to avoid errors, and relies upon fewer suspect capacities in obtaining its knowledge; it does not rely upon introspection, or upon some curious faculty for discerning the normative rules which govern the correct or ideal functioning of the mind (CW1 166ff).

Thus, Peirce defines logic, not as a descriptive or normative theory of human thought and inference, but as part of a general study of representations such as propositions and arguments. It restricts itself to a particular set of the facts about representations—those involved with the reference of words and predicates, the truth conditions of sentences and the validity of arguments, and classifies arguments in ways that are relevant to our concerns with discovering the truth. Since linguistic objects and thoughts are alike representations—this will receive further discussion in section 4 of this chapter—the study of representation will yield information about the ‘forms of thought’: however, logic benefits from abstracting from this aspect of them and studying publicly accessible linguistic expressions of arguments.

Peirce’s project extends beyond providing a ‘formal’ non-psychological account of the validity of the different forms of deductive inference. He wants to provide an explanation of the inferences that are central to the growth of scientific knowledge, to classify the different kinds of ampliative argument and provide an objective explanation of their validity. The importance he attaches to this task is evident from GVL.

According to Kant, the central question of philosophy is ‘How are synthetical judgments a priori possible?’ But antecedently to this comes the question how synthetical judgments in general, and still more generally, how synthetical reasoning is possible at all. When the answer to the general problem has been obtained, the particular one will be comparatively simple. This is the lock upon the door of philosophy. (5.348)

Peirce sees that the strongest argument in favour of the psychological approach to logic rests on the claim that a formal logic of induction is not possible, and he is aware of considerations that seem to support that claim. One can see him facing an unpalatable dilemma which suggests that either the logic of induction must rest content with describing the inductive strategies that we find it reasonable to adopt, or else it must ground induction in some metaphysical principle such as the benevolence of God. Neither horn is compatible with the autonomy of logic as Peirce conceives it: the first leads straight to psychologism, the second to grounding logic in suspect reasonings which seem themselves to cry out for logical scrutiny. The aim of the three papers in the Journal of Speculative Philosophy is to overcome this dilemma and unlock the door of philosophy. The final paper uses the results of the other two to explain the validity of induction. In the earlier papers, he attacks the assumptions upon which the dilemma rests, and provides an account of mind and reality which rests upon a rejection of these assumptions. In the following section, I shall elaborate the set of Cartesian and nominalistic assumptions which support the dilemma—they represent tendencies of thought which, according to Peirce, have tainted most European logic and epistemology.

Peirce’s underlying motivations are metaphysical. As will become clearer in the third chapter, he saw his work as part of an attempt to carry through successfully the project that Kant attempted in the first Critique: much of his work in logic was prompted by the recognition that it would be necessary to correct Kant’s logic before an adequate system of categories could be constructed. In one of the papers in the Proceedings of the American Academy, the points are given a straightforwardly Kantian cast. The motivation for having a non-psychological logic was that Peirce shared the opinion of ‘several great thinkers’ that the only successful method of inquiry in metaphysics ‘yet lighted upon is that of adopting our logic as our metaphysics’ (CW1 490). Thus, our logic will provide a non-psychological examination of the forms of human thought; and the account of synthetic inference will explain how we are able to unify the manifold of our experience. And, in advancing to explain the ‘grounds of validity of the laws of logic’, both deductive and inductive, Peirce presents a distinctive and original metaphysical view.

Let us now turn to some of the details of the position Peirce defended in these papers. I should stress, once again, that these are early papers. They reflect views not yet fully formed, and, in spite of Peirce’s subsequent admiration of them, we must recognize that they contain a lot that is sketchy, confused and obscure; many of the positions we find in them were quickly superseded. Since their influence has been considerable, they cannot be ignored in a book-length treatment of Peirce’s philosophy. Moreover, offering a reading of them serves two further purposes: it enables us to introduce some important elements in Peirce’s thought and display some of their systematic connections; and it provides helpful background for understanding the ways in which his ideas developed after 1870. The discussion in this chapter will be concerned with describing and understanding the general themes that characterized Peirce’s thought at this time; I shall not evaluate the details or probe the intentions underlying some of the more gnomic remarks that the papers contain. In this respect, the discussion is still introductory, preparing for the examination of Peirce’s mature doctrines in subsequent chapters.

2 Nominalism and the spirit of Cartesianism

The first section of the second of the 1868 papers, CFI, repudiates the ‘spirit of Cartesianism’: Cartesianism is distinguished from scholastic philosophy by four errors about the nature of knowledge and philosophical method. Each of the four distinctive marks of Cartesianism represents a departure from a truth which had earlier been acknowledged.

(1) It teaches that philosophy must begin with universal doubt; whereas scholasticism had never questioned essentials.

(2) It teaches that the ultimate test of certainty is to be found in the individual consciousness; whereas scholasticism had rested on the testimony of sages and the Catholic church.

(3) The multiform argumentation of the middle ages is replaced by a single thread of inference depending often upon inconspicuous premisses.

(4) Scholasticism had its mysteries of faith, but undertook to explain all created things. But there are many facts which Cartesianism not only does not explain but renders absolutely inexplicable, unless to say that ‘God makes them so’ is to be regarded as an explanation. (5.264)

Peirce claims that ‘modern science and modern logic’ require that the Cartesian assumptions be rejected and call for something closer to the scholastic outlook. His four counterclaims represent doctrines that he often restated. Universal doubt is a fiction, and we should not pretend to doubt what we have no real reason for doubting. We should contribute to the progress towards knowledge of a community of inquirers, trusting to the ‘multitude and variety’ of our reasonings rather than to the strength of any one. Our reasonings ‘should not form a chain that is no stronger than its weakest link, but a cable whose fibres may be ever so slender, provided they are sufficiently numerous and intimately connected’ (5.265). Finally, philosophy should never allow that anything is absolutely inexplicable. Peirce presents an attractive picture of philosophy as a fallible communal form of inquiry. However, simply as a set of claims, what he says does not undermine Cartesianism. Cartesians are likely to deny that the method of doubt is unmotivated or impossible, and point to the first Meditation as providing a justification for the strategy. Moreover, they will hold that communal and fallible methods cannot answer to the sorts of problems that concern the philosopher or logician. So, do Peirce’s remarks have any argumentative weight at all?

One way to take them is as a reminder that, according to the Cartesian, the methods to be employed in philosophy are very different from those employed in other fields of inquiry; the burden of proof lies with someone who holds that philosophy is subject to the Cartesian’s special constraints. The Cartesian assumptions are not built into the way that central philosophical problems present themselves; additional argument is required to persuade us that the question ‘How is synthetic inference possible?’ cannot be approached in the fallibilist spirit that we normally employ in theoretical inquiries. Now, Peirce believed that certain not implausible assumptions—those that make up the picture he described as ‘nominalism’—could be used to support the Cartesian outlook. It is these assumptions that yield the dilemma mentioned in the previous section: indeed, that dilemma can be seen as a case of clause 4 of the definition of Cartesianism—the validity of induction is either inexplicable or attributable to something like the benevolence of God. Thus, the first of the papers is, largely, devoted to undermining these assumptions, and the second to elaborating a framework which does not incorporate them. As is suggested in 5.265, Peirce does not have to be constrained by the requirements of the Cartesian method in attacking the assumptions which make that method attractive.3

What Peirce is criticizing is a picture which is manifested in a wide variety of philosophical theories; hardly any major philosopher escapes being called a nominali...

Table of contents

- The Arguments of the Philosophers

- Contents

- Preface

- Note on references

- Introduction

- PART ONE Peirce’s Project: the Pursuit of Truth

- PART TWO Knowledge and Reality

- Notes

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Peirce-Arg Philosophers by Hookway,Christopher Hookway in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.