China: a state or a market system?

This chapter reflects on the role of the state in China’s economy and its banking system. A proper understanding of how the mainland works in this regard is central. At the heart of the matter is this main issue: On the one hand, China has come a very long way from a traditional communist economy, where the state had full control of all assets and authority over almost every commercial transaction; after three decades of reforms, there is no doubt that the mainland has become much more market-oriented. On the other hand, the government still formally owns and runs a sizeable chunk of the system and, in particular, the ‘commanding heights’ of heavy industry, capital-intensive services and the financial system.

As a result, describing China’s economy can resemble the tale of the blind men and the elephant; there’s plenty of evidence to support the most contradictory arguments. If you want to portray the state economy as a ‘basket case’ with chronically loss-making firms, excessive bureaucratic intervention and highly distorted incentives, you can always find data to argue your case. By the same token, if you wish to trumpet the state role as positive and pro-market, with healthy companies and very limited interference, supporting figures are also readily to hand.

How should we view the situation? As usual in such cases, ‘the truth’ is likely to be somewhere in the middle, but as I conclude below, it is much more useful and accurate to think about today’s China as a predominantly market economy with a few state-induced distortions, rather than a traditional socialist system with a mere market veneer. This, in turn, implies a more stable and sustainable growth outlook than the casual observer might assume. Here are the keys to supporting this perspective:

• The state share of the economy is still sizeable. The government still owns a significant share of the economy, a good deal larger than in other Asian countries. State commercial enterprises account for 26 per cent of Chinese GDP and more than half of productive assets although they employ only 5 per cent of the workforce.

• Even the state economy is now market-driven. Despite high levels of ownership, however, the government allows market forces to control its assets to a surprising extent. Although most state firms still have a bureaucratic internal management structure, they are not subsidized, operate in a highly competitive environment and face closure or restructuring if they cannot pay their bills. From the point of view of macroeconomic performance, this is more important than the issue of formal ownership.

• As a result, state firms are profitable. The state enterprise system in China is generally profitable – more profitable, in fact, than the private sector – without the quasi-fiscal ‘black holes’ that characterize many emerging markets. And corporate management is improving over time. In this sense, the market can be viewed as winning.

• The main distortions are in the financial system. Over the past decade the real problem has been government ownership of the financial system and poor lending discipline, which left China with a chronic tendency to over-invest. When the authorities didn’t maintain macro control, the economy went through sharp boom/bust cycles, which in the mid-1990s resulted in mass closures and tens of millions of layoffs. This is not a state enterprise problem per se, but rather a factor affecting the whole economy.

• The economy is moving in the ‘right’ direction. The government is now doing a better job in managing macroeconomic cycles and is picking up the pace on its divestment of state assets. Most important, for the first time in China’s post-war history, we now see an exit strategy for the state banking system (which I refer to in more detail later in the chapter). These changes have resulted in a visibly more stable growth pattern over the past eight years.

• Still a work in progress. Where do these changes leave us? Well over halfway along the path – but keep in mind that China still faces a significant task ahead in liberalizing the financial system and pursuing formal privatization. The current system may be much more Margaret Thatcher than Karl Marx, but at the end of the day the mainland’s market economy is still very much a work in progress.

How we get there

This chapter is not meant to be an encyclopaedic examination of the history of Chinese state enterprise management and restructuring. Instead, it adopts a topical summary approach, focusing on key issues and statistics that will give investors a comfortable grasp of where things stand and how the state is run and managed.

In particular, the chapter looks at the classical pairing of ‘ownership’ and ‘operating environment’. On the ownership front, it asks an interrelated set of questions including: how big is the formal state? Where are the assets located? How many people actually work for the government or for SOEs? With regard to the market environment, how does the state intervene in the economy? What are the tools at its disposal? And how has the state’s role evolved over time? Is the state sector more or less profitable than the private sector? How do they coexist? What does this mean for macroeconomic control and microeconomic efficiency? And what is the current strategic thinking regarding the future of the state?

Who are ‘the players’? Defining key terms

Before jumping to the main analysis, we need to define our terms. One of the main difficulties in China is actually agreeing on what the state is, and how to measure it, especially since the terms have changed significantly over time.

The first point to note is that the ‘state’ in China includes both governmental operations as well as state-owned commercial entities. The former is the standard government apparatus that exists in any country, comprising the civil service, educational institutions, hospitals, cultural organizations, etc. In Chinese parlance, all of these are referred to as ‘administrative units’ (and, confusingly, are often included in state-owned enterprise (SOE) statistics). For the purposes of this analysis, this part of the state sector is not particularly interesting. Instead, my focus is on the state’s role in commercial activity, i.e. agriculture, industry and construction, as well as service sectors such as transportation, communications, trade and finance. This is where most of the arguments over ‘state economy’ vs. ‘market economy’ arise – and where China has always differed most significantly from other emerging and developed countries.

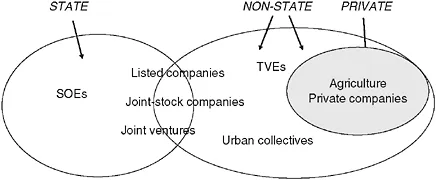

As of the early 1980s, the situation was relatively straightforward, in that almost all economic activity was owned and controlled by the state in one form or another. The agricultural sector was made up of communes. Urban industry and services were dominated by SOEs. Everything else was pretty much divided into so-called ‘township and village enterprises’ (TVEs), which operated outside the cities, and urban collectives for small-scale urban activity. These last two were never formally integrated into central economic plans, but were still solidly state-owned in theory. For institutions of any size, managers were directly appointed by the government, and in the rest they were elected by the collective.

Over the past 25 years, however, things have changed radically. To begin with, nearly all of agriculture was taken almost immediately out of public hands, as the communes were broken up and each family was allocated individual plots of land. Next, the various smaller-scale TVEs and collectives drifted gradually out of state control as the economy liberalized. Today they still exist in the hundreds of thousands, but they are effectively private companies, without access to state financing and without significant interference by local authorities. In fact, in the absence of a legal framework for private enterprises, most new start-ups went under the guise of TVEs and collectives right through the late 1990s.

Since 2000, the patchwork has become more complicated still. The truly private sector has taken off, with tens of thousands of new and formally private enterprises established (this process is particularly well developed in coastal provinces and cities, while collectives still dominate in smaller, more inland destinations). In most sectors, foreign companies are no longer required to have a joint-venture partner, which has led to an explosion of wholly-owned foreign firms in China as well.

The most important recent trend, however, has been the blurring of lines within the SOE sector itself. In Chinese usage, the term traditionally refers to a commercial entity fully owned and managed by the state, as opposed to other legal forms of ownership or incorporation. However, as we discuss further below, many smaller state firms have been de facto privatized, whether through buyouts or gradual management takeover. Many more were closed down after the bursting of the mid-1990s bubble sent entire sectors into insolvency. In the remainder, mixed ownership is increasingly the norm with, for example, a large portion of the roughly 100,000 foreign joint ventures in China created through tie-ups with state enterprises. The vast majority of listed companies on domestic and foreign markets come from the ranks of state-owned firms. And state firms are actively inviting outside investment from other domestic sources as well, creating new hybrid joint-stock and limited liability companies.

In this environment, it no longer makes sense to talk about state vs. private companies as we see so often in the press. Instead, from an ownership point of view, the more relevant distinction is between ‘state’ and ‘non-state’ firms, where the former are both owned and to at least some degree actively managed by the government, while the latter are either held outright in private hands or (more commonly) have notional state ownership but no real government role in their affairs. A rough breakdown is given in Figure 1.1.

From Figure 1.1, you can already sense how difficult it is to accurately gauge the true scope of the state sector. For instance, how should we treat the

mass of quietly privatized small and medium SOEs that still show up in the formal statistics as state-owned companies? By the same token, what do we do with SOEs that have sold part of their equity to outside interests through listings or joint ventures but where the state still has a direct 70 per cent share? Or a 40 per cent share? These issues are addressed in the next section.

Formal ownership: how big is the state?

This section addresses the formal size of the state sector relative to the overall economy; given the myriad constraints in the data discussed above, here is how I shall proceed. To begin with, the existing statistics for SOEs and other state institutions are taken at face value, including firms where the state has a controlling interest (so-called ‘state-controlled’ firms, defined as any enterprise where the direct and/or indirect state share is over 50 per cent). In general, this approach overstates the actual level of state ownership by including privately held shares in state-controlled firms – for example, shares held by retail investors in listed public companies – as well as de facto privatized companies that still appear on the books as state-owned. On the other hand, it might also understate ownership by excluding firms with a large minority state share.

As we will see further below, focusing on ‘ownership’ also strongly exaggerates the role of the state in the economy, but it’s still very important to understand what is sitting on the books of the government from the legal point view.

Important point: please note that unless otherwise stated, from here on the term ‘SOE’ in the chapter (and figures) refers to the broader definition above, including both traditional 100 per cent state-owned as well as ‘state-controlled’ commercial firms.

The state and the economy

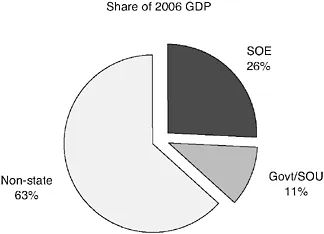

Our first snapshot is the size of the state, using the ownership concepts defined above, as a share of Chinese GDP or total value-added in the economy. The breakdown is shown in Figure 1.2.

The estimates in Figure 1.2 show that state administrative units (such as the civil service, healthcare, science and education) accounted for some 11 per cent of 2006 GDP. State-owned and state-controlled firms in all sectors made up another 26 per cent of Chinese value-added and ‘non-state’ ownership, as defined in the previous section, accounted for the remaining 63 per cent. In other words, on an ownership basis, the state now accounts for around 30 per cent of all (non-administrative) commercial activity in China.

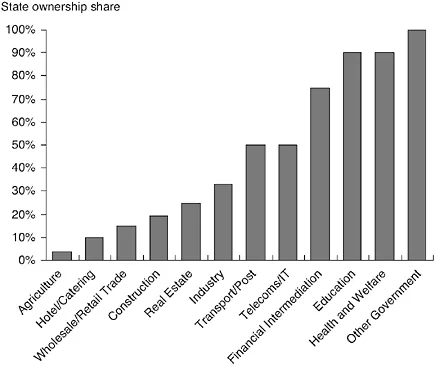

How were these estimates obtained? By beginning with official data for GDP by industry, and then using available statistics for state ownership in each productive sector. Figures are directly available for agriculture, manufacturing and construction; for the various services sectors partial data are used to generate the above calculations. As you can see from Figure 1.3, the state is virtually

absent from the agricultural sector, owns between 15–20 per cent of labour-intensive services such as construction, trade and catering, controls nearly one-third of industrial capacity, and has a much larger share of other services, including telecommunications, finance and direct government functions.

Needless to say, using GDP shares is not the only way to look at the size of the state....