Chapter 1

Pedestrianism

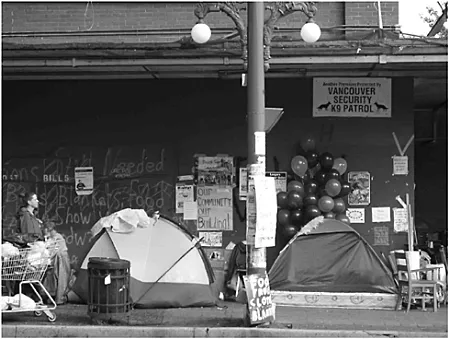

In 2002, radical anti-poverty activists occupied the site of the former Woodward’s department store, located in the centre of Vancouver’s impoverished Downtown Eastside, in what became a high-profile protest over gentrification, government cutbacks and homelessness. Forced out of the building, the squatters established an encampment in the surrounding sidewalk that quickly grew in size, attracting many other activists and homeless people (Figure 1.1). ‘Woodsquat’, as it was quickly dubbed, was many things to many people: a visible expression of radical anger, a deliberate attempt at embarrassing the provincial government and city in the run-up to the bid for the 2010 Winter Olympics, a symbolic space of opposition to private property and an affirmation of the commons, an eyesore and a civic embarrassment, a space of carnival and celebration, an affront to public salubrity and a resource centre and safe refuge for many homeless people. Tents, sleeping bags, posters, couches, dogs and people intermingled. Highly politicized, Woodsquat activists invoked a language of rights, social justice and insurgent citizenship. The City obtained an injunction, compelling the protestors to remove the encampment. Finally, a negotiated settlement occurred, and the protest was disbanded in late 2002.

How are we to make sense of Woodsquat? What analytical frame can be brought to bear? I suspect that for many scholars, the temptation is to fit Woodsquat into prevailing conceptual categories. We can think of the protest and the official response through the lens of social justice and citizenship, for example. Imbued with a language of rights, the protest can be described as a critique of the fairness of a social order and its attendant distributions of rewards and costs. We may also view the protest through the lens of property, as a challenge to dominant forms of private property, and a defence of popular, localized commons. Located on the street, in public view, we may also be tempted to invoke conceptions of public space, appealing to the importance of such sites for the exercise of expressive rights, and the forging of expansionary forms of citizenship. The actions of the city, conversely, could easily be characterized as a manifest injustice, motivated by a desire for the purification of public space.

All of these perspectives are, in their way, valuable and important. Indeed, I have contributed to them myself (Blomley 2008a). But they are, I wish to suggest, partial.

Levi (2009) notes a ‘law-first’ tendency in socio-legal scholarship in which, all too often, phenomena are subsumed within a legal category. When presented with a material phenomenon, such as the gated community (his example), legal scholars tend to reduce and explain it with reference to an ‘underlying’ legal category (such as private property). Arguably, something similar happens in relation to public space literature: when socio-legal scholars approach the topic, they tend to do so through already constituted legal categories, such as public property, rights and citizenship. Indeed, to invoke ‘public space’ is to introduce, even if unwittingly, notions such as the Habermasian public sphere. While such legal frames are clearly germane, there is, perhaps, a related danger of missing important realities. If our choice of vocabulary shapes our understanding, we need to be alert as to how the adoption of a priori framing, such as ‘public space’, not only opens but also closes down scholarly analysis, in much the way as for the hammer, every problem is a nail.

This becomes clearer if, rather than reaching for the hammer of abstraction, we temporarily shelve it, and pay more careful attention to the seemingly mundane details of the dispute, in particular, the quite striking way in which the City argued before the court. The City was quite clear, in its written arguments, that it was not framing the issue with reference to abstractions. The application for an injunction was, it stated, not ‘about homelessness and poverty. It is about the right of the City … to have a valid bylaw which is presumed to reflect public policy and to balance the competing interests of all citizens. …’1. In response to the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association (BCCLA), who intervened on behalf of the protestors to argue that the City should exercise its authority in a manner consistent with constitutional values, notably the right of the protestors to freedom of expression, the City made clear that as far as it was concerned, constitutional rights were irrelevant to the case. The City owned the streets and had the authority to regulate those streets in public interest. The City insisted that it was not targeting people and their behaviours, but was concerned only about the specific arrangement of a set of material objects in a particular space: ‘The injunction sought is directed at structures and objects only. The City is not seeking to enjoin lawful picketing or protest or assembly on the Sidewalks’2. Insofar as the City was concerned, Woodsquat was not a site for politics and citizenship, but a series of obstacles, which they dutifully listed (‘tents, sofas, chairs, mattresses, tarpaulins, tables, buckets, shopping carts, traffic delineators, traffic cones, wood pallets and other items or objects’)3. The presence and location of these items were said to be a contravention of municipal law, notably Section 71 (1) of the Streets and Traffic By-law, which forbids any person from placing ‘any structure, object, substance or thing which is an obstruction to the free use’ of the street or side-walk. But while the mere unlicenced presence of these objects was objectionable, it was the particular location and spatial arrangement of these things that was deemed more worrisome, as they compromised pedestrian passage. The City characterized the sidewalks as ‘very busy pedestrian thoroughfares. The City regulates the placing of structures and objects on its sidewalks with the primary purpose of ensuring safe, efficient and unobstructed pedestrian access’4.

Moreover, rather than framing these objects as somehow inherently ‘public’, to the extent that they were components of a form of public speech, or the possessions of a socially disadvantaged population, many of whom were homeless, and thus compelled to live their lives in public view, the City characterized them as a form of private encroachment, akin to the unlicenced sidewalk café: ‘By placing tents, mattresses and other structures on the Sidewalks, the Defendants have effectively appropriated large portions of the public Sidewalks to their private use and are depriving the rest of the public of the use of those Sidewalks’5. As such, they constituted a ‘trespass’6 on City property and an affront to the public good.

The City’s framing of Woodsquat is an example of a pervasive and widespread form of urban public space governance. While powerful, it tends to be hidden from view, easily obscured by grander and more visible forms of urban regulation. This book seeks to make sense of the character and effects of this rationality, which I call ‘pedestrianism’. Pedestrianism understands the sidewalk as a finite public resource that is always threatened by multiple, competing interests and uses. The role of the authorities, using law as needed, is to arrange these bodies and objects to ensure that the primary function of the sidewalk is sustained: that being the orderly movement of pedestrians from point a to point b. Obstacles that impede flow are inherently suspect, according to this logic, and are to be limited or placed carefully so as to minimize blockage. Law provides the essential ordering mechanism to ensure structured flow.

The motivation or inner life of the pedestrians is not an issue for pedestrianism, nor is their social standing. Beggars, protestors, commuters at a bus stop or patrons at a sidewalk café are all potential obstructions. Some of those obstructions are manifested as things, such as the ‘structure, object, substance or thing’ at issue at Woodsquat, and some as bodies, such as people waiting at a bus stop. The bus stop and the waiting transit user are in this sense comparable. Pedestrianism values public space not in terms of its aesthetic merits, or its success in promoting public citizenship and democracy. Rather, the successful sidewalk is one that facilitates pedestrian flow and circulation. Rather than seeking to promote and enhance a Habermasian public sphere that is distinct from the state, pedestrianism views the sidewalk as a form of unitary municipal property, held in trust for an abstract public. The municipality has a formal duty to regulate the sidewalk in the name of the public good. Other sidewalk users – such as the Woodsquat protestor, the beggar or the abutting merchant or homeowner – are not thought of as members of alternative publics, so much as they are deemed trespassers, impinging and encroaching upon municipal space.

Pedestrianism and police

To make sense of pedestrianism requires a few theoretical and methodological tools. The first, following Levi (2009), is the requirement that we recognize and treat pedestrianism on its own terms. Pedestrianism is clearly a form of legal practice and knowledge, but is also distinct, eschewing a rights frame in favour of an attention to placement and flow. Thus, perhaps it is better to think of it as a particular legal knowledge, with its own networks, logic and internal truth (Valverde 2003; Riles 2005). In making sense of such legal complexes, Valverde (2003) suggests that we avoid the temptation to immediately ask the grand questions (‘why?’, ‘what?’), or follow the path of revealing the interests that are being furthered by law. While this is still necessary, she also suggests that we can learn much by studying legal knowledges, such as pedestrianism, through an exploration of their effects: that is, by asking ‘what a limited set of legal knowledges and legal practices do, how they work, rather than what they are – much less what this all means for globalization, patriarchy, or any other grand abstraction’ (2003, 11). To focus on effects, she argues, is necessarily to explore the ‘particular effects of particular practices’ (2003, 14). In so doing, we are invited to explore ‘the particular effects of the techniques used by various organizations and institutions to organize, sort, classify, relate and explain’ (2003, 14). Here we can learn from fields such as science studies, in which we are encouraged to ‘bracket our familiarity with the object of study’, approaching it as an anthropologist would a remote culture (Latour and Woolgar 1985, 277) or the work of political geographers, who encourage us to consider the state as an effect, produced through a set of mundane and messy bureaucratic practices (Painter 2006; Mountz 2003).

When we take the specific legal practices and knowledges that constitute pedestrianism seriously, on its own terms, it becomes easier to recognize that it entails a very specific and somewhat unfamiliar conception of state power, law and governance. Pedestrianism can usefully be understood as a particular manifestation of a long-established tradition of ‘police powers’ that seek to promote the well-ordered society through regulations governing such miscellaneous matters as weights and measures, the sale of dangerous goods, street lighting and market opening hours. Remarkably wide-ranging, police powers have been characterized as the ‘most expansive, least definite and yet least scrutinized of governmental powers’ (Dubber 2004, 101). While police powers are operative at all levels of the state, they are most active at the local level, exercised by minor functionaries such as planning officials, liquor control boards, municipal engineers and environmental health officers. The objects relevant to police powers, Foucault (2007, 335) notes, are ‘urban objects’ in the sense that they exist only in towns, existing under conditions of ‘dense coexistence’.

Police powers, Dubber (2005) argues, have ancient roots, reflecting a patriarchal tradition of governance, premised on the model of the household as a unit of governance. For example, early Frankish law rested on the protection of the mund, or household, in which the householder enjoyed authority to protect his household against external threats, and exercised internal powers to discipline recalcitrant members of the household. Such powers were not arbitrary, but were to be wielded so as to ensure the welfare of the household as a whole. The centralization of royal power entailed the expansion of the kingly mund, or the royal peace, to the nation as a whole, such that all became, in effect, members of the royal household. The sovereign was thus charged with protecting his realm from external threats, but was also required to order the members of his household to ensure the survival and welfare of the household as a whole. Those who were recalcitrant or disobedient, thus breaking the royal peace, were seen as violating their duty of fealty and were thus disruptive of the order of the household.

This hierarchical membership model, premised on the preservation of the household, continues to underlie modern police power, argues Dubber. So, for example, Blackstone defined nuisance as a police offence, it being ‘an offence against the public order and economical regimen of the state; being either the doing of a thing to the annoyance of all the king’s subjects, or the neglecting to do a thing which the common good requires’ (1769/1979, 167). As Dubber (2005) notes, such omissions and commissions entail a failure to perform a duty of orderly conduct, ‘of acting according to one’s proper place in the community-family. Any violation of this duty amounted to a challenge to the authority of the householder, who bore the responsibility of maintaining order’ (96). Police powers seek not to protect identifiable persons, but rather govern in the interests of more nebulous abstractions, such as the public good, the community, or what Blackstone referred to as the ‘domestic order of the kingdom’ (1769/1979, 162). Viewed this way, the actions of the Woodsquat protestors entailed a violation of civic duty and a disruption of the orderliness of the larger community.

Police powers, therefore, should be seen as a distinct mode of governance, unlike that operating through prevailing forms of liberal legality, argues Dubber (2005; though cf. Novak 2008). If autonomy, or self-government, underpins law, then police is premised on heteronomy, or government of people by the state. The state itself, moreover, is differently conceived, he points out. From the perspective of law, the state is the institutional manifestation of a political community made up of autonomous equal persons. The function of law is to preserve the autonomy of these subjects. From the perspective of police, however, the state is the ‘… institutional manifestation of a household. The police state, as paterfamilias, seeks to maximize the welfare of his – or rather its – household’ (Dubber 2005, 3).

Police powers, such as those relating to the regulation of the sidewalk, operate both through the suppression of ‘nuisances’ (such as sidewalk blockages) and the promotion of desired forms of behaviour and conduct. Rather than a form of remedial regulation, like the criminal law, police powers are also preventive in orientation. In the Woodsquat case, the City not only punished those who had caused an identifiable obstruction that impeded particular persons, but also prudentially sought to forestall future obstructions. For Bentham, while criminal law ‘regards in particular offences already committed; [its] power does not display itself until after the discovery of some act hostile to the security of the citizens’, police power ‘applies itself to the prevention both of offences and calamities; its expedients are, not punishments, but precautions; it foresees evils, and provides against wants’ (quoted in Dubber 2004, 136). In that sense, police powers act as a ‘hinge articulating the past-oriented punishment of wrongdoing with the future-oriented governance of risks and dangers’ (Dubber and Valverde 2008b, 4).

Operative at lower levels of the state, through apparently mundane forms of regulation, police powers are easily overlooked. But this would be a mistake. Police powers are remarkably promiscuous, open-textured, flexible and far-reaching. The objects of police are particularly heterogenous, including people, acts and objects, exemplified by the routine production of long lists of apparently disconnected problems and situations, the selection of which is rarely justified, in the service of remarkably open-ended categories, such as ‘nuisance’, ‘obstruction’, or ‘morality’. Take, for example, the 1907 Streets By-Law in Vancouver that forbade, inter alia, sports or amusements likely to frighten horses or ‘embarrass the passing of vehicles’, the cutting of firewood, lumber, block, rock, stone and the mixing of mortar, ‘or any other act upon the sidewalk’ which obstructs pedestrians; required that road users keep to the left side; prohibited indecent exposure, the public display of ‘obscene materials’ and displays of books and pamphlets devoted to criminal accounts, police reports or accounts of criminal deeds, or ‘pictures or stories or deeds of bloodshed, lust or crime’; and banned the use of poison for man, animal or fowl in public places, the throwing of sharp things that may damage trees or injure horse’s feet; and the discharge of ‘liquids which cause filthy effluvia’. Some of these prescriptions were quite specific, such as the requirement that youths remain under curfew between 9 pm and 6 am, unless with an adult or on an errand, and then to not loiter, shout or yell. Others seemed remarkably open-ended, such as the injunction against ‘loitering’, ‘collecting in crowds’ and ‘encroaching’7. The City’s contemporary preoccupation with the offending ‘tents, sofas, chairs, mattresses, tarpaulins, tables, buckets, shopping carts, traffic delineators, traffic cones, wood pallets and other items or objects’ in the Woodsquat case, and their invocation of ‘access’ and its negative, ‘obstruction’, continues this pattern.

Similarly, Dubber (2004) notes that police is comprehensive and universalizing: it could be ‘applied to everyone and everything and everyw...