Outside the House That Ben Built

As the act of going to a store to shop was still a relatively new phenomenon in the nineteenth century, the shop front was an evolving architectural form.3 Before in-store shopping became common in urban areas, smallish consumer

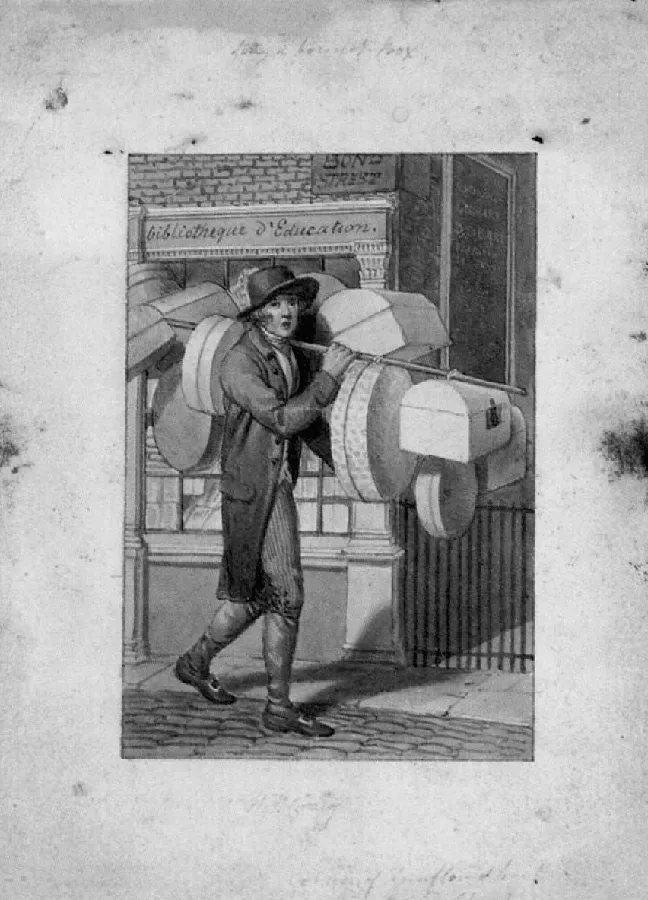

items were sold either in market stalls or by people carrying their particular wares (hatboxes, flowers, fish) displayed on trays, in baskets, or strung on poles. “Indoor spaces,” as Elizabeth Kowaleski-Wallace explains in Consuming Subjects: Women, Shopping and Business in the Eighteenth Century, “would have been too dark to allow the customer to scrutinize the goods.” It was only with the “improved manufacture of glass for windows” and indoor and outdoor lighting that indoor shopping became a viable activity at all (Kowaleski-Wallace 80). As it happens, there is an image of Tabart’s shop (Figure 1.2) that captures the transitional moment between the indoor shop and the outdoor tradesman hawking wares on the street.

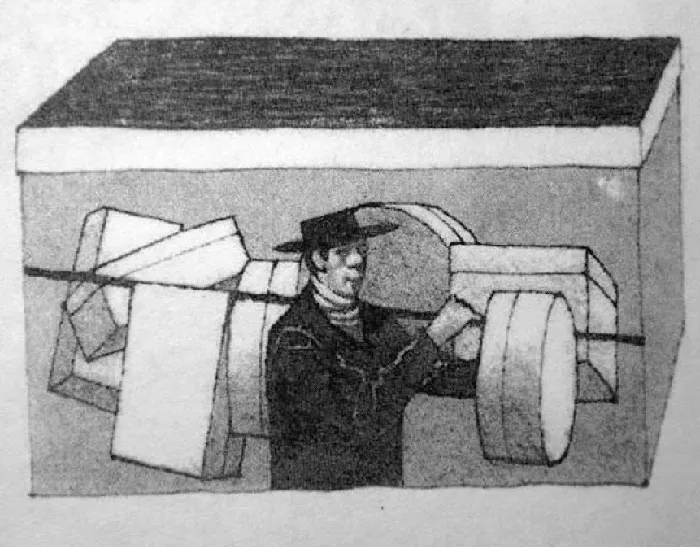

The watercolor is by William Marshall Craig—an artist who also produced illustrations for Tabart and his mentor, publisher Richard Phillips (1767–1840). It is one of a series of watercolors, commissioned by Phillips, of street vendors selling their wares in front of famous London landmarks. The fact that the “Band Box” (also known as a bonnet box or hatbox) seller is painted in front of Tabart’s shop becomes, in itself, a statement about the importance of the address. The hatbox seller in the foreground—with only the “Bibliotheque d’Education” and the street sign “Bond Street” visible in the background—suggests a scrambled visual link between French fashion and the bookshop. The marketing message is that books were not only educational, but also fashionable as accessories. Fenwick exploits the same conceit in Visits to the Juvenile Library. The advertisement itself, incidentally, was arresting enough to attract the attention of the children’s book artist, Charles Keeping (1920–88), who used the image, with its strong cubes, to accompany a poem by Charles Causley, “Song of the Shapes” (Figure 1. 3).

The bonnet box seller walking in the streets of Craig’s early-nineteenth-century illustration/advertisement for Tabart was a character quickly becoming an historical curiosity, a relic of a disappearing age. Once shops started to move indoors, says Claire Walsh in “Shop Design and the Display of Goods in Eighteenth-Century London,” they began to develop distinguishing characteristics:

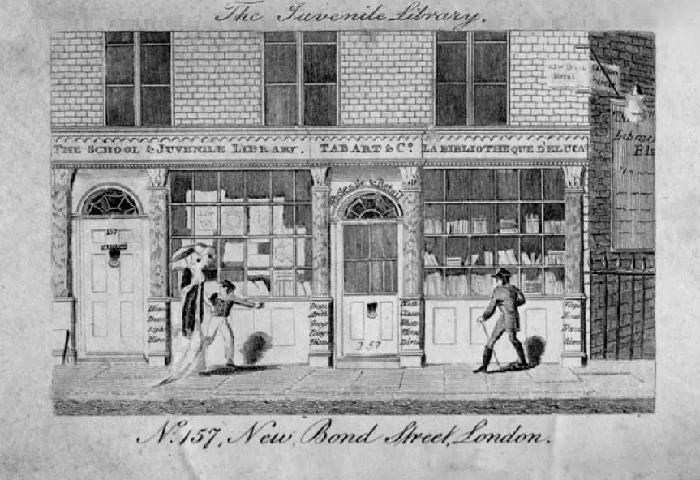

The 1805 engraving of Tabart’s shop (Figure 1.1) shows several of those features, including the painted surround and large windows (though they do not appear to be bow windows). As Claire Walsh says they are designed to do, these features function to attract the attention of the passing, fashionable public. They also provide additional information (Figure 1.1). Over the door,

the sign reads “Wholesale and Retail,” while the door posts are inscribed with some of the genres of the books within. Partly visible are the words “Classics,” “Biography,” “Geography,” and “History”; subjects as completely familiar to schoolchildren today as they were in the eighteenth century.

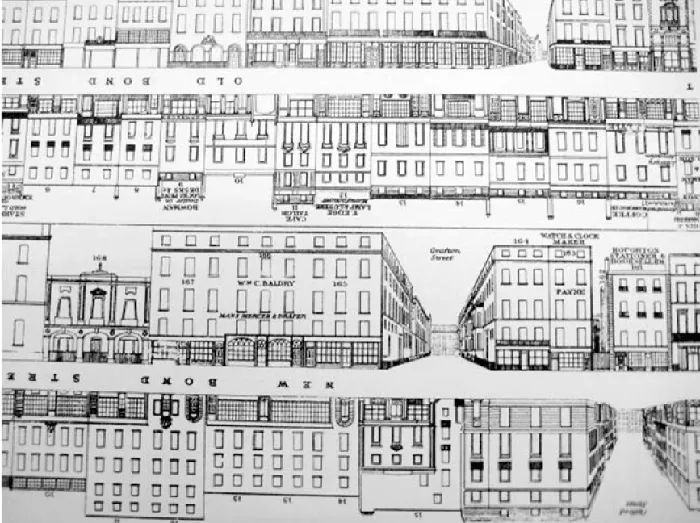

Tabart’s Juvenile Library in the 1805 engraving was on the corner of New Bond Street and Grafton Street in London, a neighborhood which was emerging as a fashionable shopping destination (Figure 1.4).

Walk to the same corner today and you will find one of the most glittering retail precincts in London, filled with high-end jewelry stores, their sparkling wares attractively displayed behind transparent walls of wrap-around plate glass windows. The goods behind the glass are designed to entice shoppers inside, and yet, at the same time, are protected by elaborate security systems and very large guards whose job it is to keep out unsuitable people. Asprey’s, a jewelry and luxury goods shop, now occupies the corner of New Bond Street and Grafton Street that used to be Ben’s. The panes of glass that made up Ben’s display window were smaller—modern plate glass had not yet been invented—but the lineaments of the building are visible in Asprey’s, especially in the look of the upper-story windows (Figure 1.5).

Shoppers on New Bond Street today regard big windows filled with artfully arranged goods as normal, but in Ben’s day they were a novelty, though

designed to the same purpose: to catch the eyes of people who are otherwise just passing by and entice them to stop and enter the magical world on the other side of the glass. Because modern shoppers take seductive window displays in stride, it is difficult to grasp just how innovative they were two hundred years ago. We’ve become so inured to the lure of goods attractively lit and displayed in shop windows that we’ve lost the memory of the originality and cleverness of the idea.

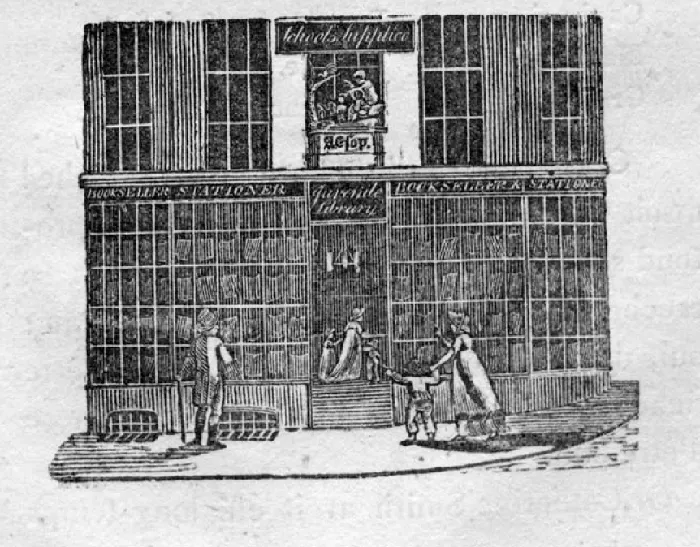

A description of the allure of the bookshop windows of one of Tabart’s famous competitors does exist, however. The Juvenile Library (as it was called) was that of the political philosopher, William Godwin (1756–1836) and his second wife Mary Jane Clairmont (Mary Wollstonecraft, Godwin’s famous first wife, died shortly after giving birth to their eventually more famous daughter, Mary—later Shelley). Before marrying Godwin, Mary Jane Clairmont had worked for Tabart, and she brought her expertise and experience to the enterprise. By the time Mary Jane and William Godwin started up their Juvenile Library in 1805, they had five young children at home: their son William (born in 1803), Mary Jane’s two children, Charles and Claire, William’s daughter Mary, and his step-daughter Fanny (I’ll return to their stories). Peter Marshall, in his biography of Godwin, describes the bookshop with its “stone carving of Aesop” (Figure 1.6) over the entrance.

“A passer-by” recalls that a former child patron of the shop “could easily peer through the immense low display windows and see the counters laden with books, with Mrs. Godwin and her assistants organizing the business in a back room” (Marshall 274). The young enthusiastic reader remembers “how he lingered ‘with loving eyes over those fascinating story-books, so rich in gaily-coloured prints; such careful editions of marvelous old histories’” (Marshall 274).4 This lovely description hints at the desirability of the contents to young shoppers and also suggests why the passers-by in the engraving of Tabart’s shop appear arrested by the displays. It is not, then, too far a stretch to assume that Godwin’s window displays resembled the ones depicted in the frontispiece of Visits to the Juvenile Library. The image of the child peeking longingly into the window of an unnamed bookshop, from the frontispiece to Fortune’s Football (Figure 1.7), a book published by Tabart in 1806, seems to capture the spirit of the child viewer recorded in Marshall’s biography of Godwin.

Interest in material domestic goods was awakening in a burgeoning Enlightenment middle class. The job of furnishing a home gradually became the responsibility of women, and the Bond Street shops started to offer the goods women sought. Domestic material goods were not the only kinds of home furnishings women wanted. They were also looking to fill their homes with intellectual material goods, with books and with art—the pedagogical materials their children would need. The new shoppers of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were looking for a new lifestyle, one that would reflect their interests, sense, sensibility, and their especial concern for education. Ben’s shop fit the bill extremely well.

In the 1805 engraving, prominent window displays of books and maps on either side of the door attract the attention of the ...