The impact of South Africa’s political history on its security

While space prevents a discussion of South Africa’s history generally, a brief appreciation is required.

This history centres on the struggle between the Dutch-descended people of South Africa (known as Afrikaners) and all other ethnic groups which have inhabited or controlled South Africa at various points throughout its history, including

confrontations between those of English descent and the Afrikaners. One of the single biggest misunderstandings with regard to South Africa’s past is that Afrikaner antipathy towards the English is as strong, if not perhaps greater than, their belligerence towards the various black tribes of the region, as Allister Sparks has pointed out in his remarkable study The Mind of South Africa.5

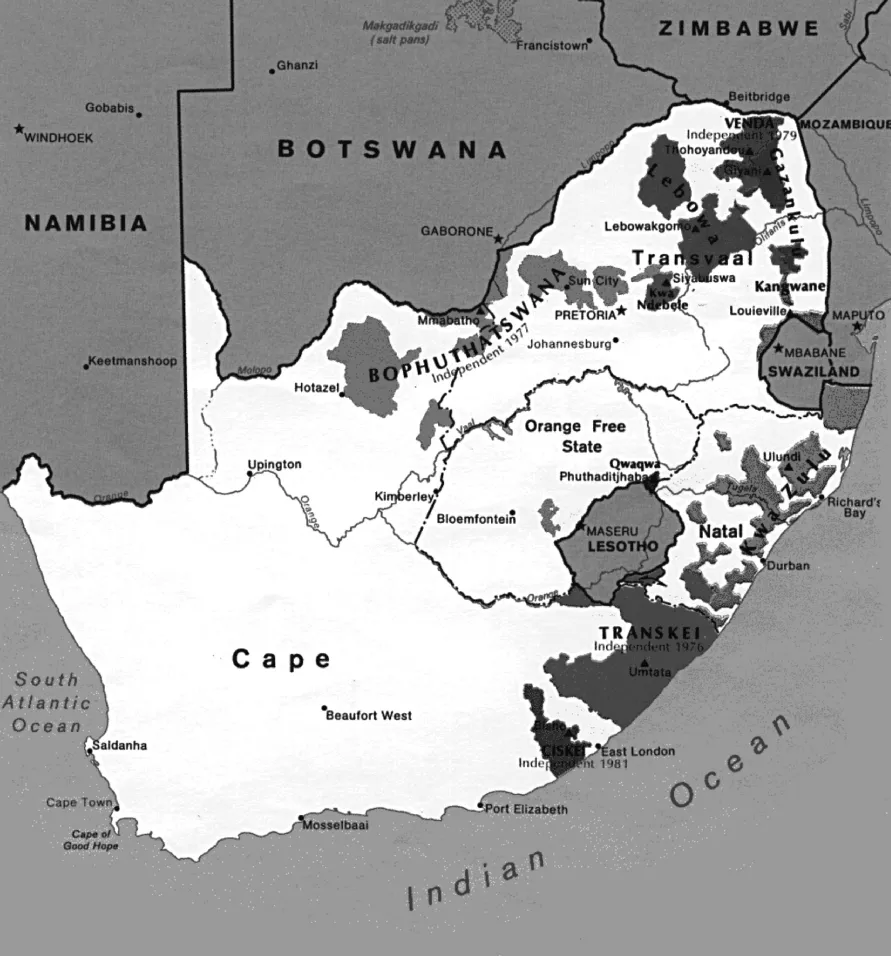

When the National Party (NP) was elected to power in 1948 and declared the policies of apartheid (“separateness”), it did so with the view that these were necessary in order to ensure the survival of the Afrikaner nation in a country where it was thought that black majority-rule would lead to genocide against the Afrikaner nation, and where the English could never be trusted. Thus, the National Party (hand-in-hand with the Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa) represented the political and cultural aspirations of the Afrikaners as “white Africans” in a country filled with black Africans.

The English were not, however, the biggest problem confronting the Afrikaners. From the beginning (1911, with the Union of South Africa, followed one year later by the founding of the ANC on 8 January 1912), it was the black tribes of South Africa that constituted the biggest perceived threat to Afrikanerdom. Over the course of the twentieth century, this view evolved to such a degree that, by the 1970s, the state believed that it was faced with a “total onslaught” by the liberation and revolutionary forces confronting it, both in South Africa and regionally – through the network of Communist guerrilla movements aligned with the Soviet Union and Cuba, fighting South Africa and its allies across Southern Africa. This twin rubric of a “black tide” sweeping the Afrikaners to their extinction in South Africa, while “black communism” would accomplish the same with their cultural and religious beliefs, drove the NP to confront these movements with every means at their disposal – and pushed it to decide that the only possible response that it could give to this “total onslaught” was to prepare a “total strategy” to confront it. Within this context, the National Party government implemented policies which reflected two forms of confronting its adversaries: overt, military confrontation; and clandestine-covert confrontation, which will form the major focus of this study’s consideration of the apartheid era and the transition from it.

From the point-of-view of the ANC and other national liberation movements, South Africa had been placed under the yoke of colonial occupation by Dutch (Boer) settlers more than three centuries previously. These Boers (and, later, the British) implemented racist policies to ensure that the black tribes who provided the labour and thus economic success to the white settlers, would remain subservient to them in perpetuity. Thus, the termination of these racist policies (which were developed during South Africa’s Union period and, by 1948, culminated in the one policy of apartheid) and the removal from political and economic power of those that propagated them was the aim of the liberation movements. They believed that, in pursuing this aim, due to the nature of their opponent, an armed struggle was morally justified.

Within this history, it will be noted – as a starting-point for this study – that South Africa’s security establishment began to evolve almost immediately following the National Party election victory in 1948; it would not, however, begin to coalesce into a truly comprehensive security architecture until the late 1960s. The apartheid regime did not have an independent intelligence service until 1961 – the year that Republican Intelligence (RI) was founded, and the year following the launch of an “armed struggle” by the ANC, the South African Communist Party (SACP) and their jointly organised Umkhonto weSizwe (“Spear of the Nation” or MK, the guerrilla army founded in June 1961 by Nelson Mandela); this was significant because the British, in their dominion capacity up to 1961 (the year that South Africa declared itself a republic and withdrew from the Commonwealth) did not allow it to have one, for reasons which will be outlined. It was, however, the events of the Sharpeville Massacre on 21 March 1960 and the subsequent launch of the ANC/SACP “armed struggle” – alongside similar efforts by the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC, a radical black militant offshoot of the ANC), and the African Resistance Movement (ARM, a group of radical-left whites whose bombing campaign between 1962 and 1964 mobilised the security establishment against such future action) – which prompted the apartheid leadership to realise that they had insufficient security and intelligence capabilities to confront these threats, and so move to remedy this over the decade. Even then, a truly effective security intelligence service (as distinct from the intelligence interests of the South Africa Police and the defence forces) did not exist until the establishment of the Bureau for State Security (known as BOSS) in 1969.

Consequently, during the period from 1960 to 1990 (the year in which the transition to a post-apartheid South Africa began) – and under the successive leadership of Prime Ministers Hendrik Verwoerd and B.J. (John) Vorster, and Presidents P.W. Botha and F.W. de Klerk – South Africa was a security state, one which used intelligence extensively to directly target its opponents both internally and externally. While nominal political authority and power rested with the elected ministers who composed the Cabinet, this was not the reality of the situation. By 1970, the true centre of power resided in the central security structures of the government – led by the State Security Council (SSC); while the Cabinet oversaw and acquiesced to all major decisions affecting the country, the SSC was the “super-Cabinet”. In its sessions, the members of the SSC made all recommendations and decisions which affected the governing of the country; ultimately, bodies such as the SSC ran the policies of “Total National Strategy” and “Total Counter-revolutionary Strategy” that ran South Africa. The authority of the wider Cabinet would not be restored effectively until De Klerk came to power in 1989.6

Intelligence in South Africa must, therefore, be seen in light of the role that it played in supporting and driving the counter-revolutionary strategies, structures and operations of the apartheid state, alongside the role it played for the exiled ANC and SACP particularly in their efforts to overthrow that state through revolutionary means. In the post-apartheid era, intelligence has continued to play a significant role in supporting the ANC’s continued efforts at introducing revolutionary change to South Africa, in many senses of the word.

Revolution, counter-revolution, and South Africa’s intelligence dispensation

It is also worth noting that in a number of senses South Africa has, in effect, been a revolutionary state since the election victory of the Afrikaner-dominated National Party in 1948. First, with the establishment of the apartheid state in 1948, the National Party and its allies (in other, more conservative Afrikaner movements and parties) sought to revolutionise the nature of the South African state to protect Afrikaner culture and political dominance – not only against the black, coloured or Indian populations that comprised the overwhelming majority of the state’s population, but also against the legacy of British control of South Africa for the first half of the twentieth century. Equally, as noted, the principal liberation movement – the ANC and its ally, the SACP – had determined in 1960 that an “armed struggle” was the only option it now faced, in attempting to overthrow the apartheid order and government in South Africa. It, therefore, began its own revolutionary efforts, which it pursued over the following three decades; this revolutionary approach led to the development of a counter-revolutionary strategy within the apartheid state’s security apparatus, which – following the 1976 Soweto Uprising and by the middle of the 1980s – saw a symbiosis of revolution and counter-revolution both inside and outside South Africa. While this conflict calmed during the negotiated settlement conc...