![]()

1

Introduction

Bangladesh is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate risks, both from existing variability and future climate change. From annual flooding of all types to a lack of water resources during the dry season, from frequent coastal cyclones and storm surges to changing groundwater aquifer conditions, the importance of adapting to these risks to maintain economic growth and reduce poverty is clear. Households have for a long time needed to adapt to these dynamic conditions to maintain their livelihoods. The nature of these adaptations and the determinants of success depend on the availability of assets, labour, skills, education, and social capital. The relative severity of disasters has decreased substantially since the 1970s, however, as a result of improved macro-economic management, increased resilience of the poor and significant progress in disaster management. Substantial public investment in protective infrastructure (e.g. cyclone shelters, embankments) and early warning and preparedness systems have played a critical role in minimizing these impacts. More investments are still required. In the long list of potential impacts from climate change, the risks to the agriculture sector stand out as among the most important.

Agriculture is a key economic sector in Bangladesh, accounting for nearly 20 per cent of the GDP and 65 per cent of the labour force. The performance of the sector, here to include crops (70 per cent of agricultural GDP), livestock (10 per cent) and fisheries (10 per cent), has considerable influence on overall growth, the trade balance, the budgetary position of the government, and the level and structure of poverty and malnutrition in the country. Moreover, much of the rural population, especially the poor, is reliant on the agriculture sector as a critical source of livelihoods and employment. Many may also do so indirectly through employment in small-scale rural enterprises that provide goods and services to farms and agro-based industries and trades.

Climate is only one input factor in an agriculture sector that is already under pressure. The achievement of food self-sufficiency remains a key development goal for the country. Significant progress has been made in the sector since the 1970s, in large part due to the rapid expansion of surface and groundwater irrigation and the introduction of new high-yielding crop varieties. The production of rice and wheat increased from about 10 million tonnes/metric tons (10Mt) in the early 1970s to almost 30Mt by 2001. The challenge now for Bangladesh is to enhance productivity, especially as demands for food increase with the growing population (1.3 per cent growth rate) and improved incomes. Moreover, overuse, degradation and changes in resource quality (e.g. salinity) will place additional pressures on already constrained available land and water resources.

Future climate change risks will be additional to the challenges the country and sector already face. Long-term changes in temperatures and precipitation have direct implications on evaporative demands and consequently on agriculture yields. Increased carbon dioxide concentrations may also impact the rates of photosynthesis and respiration. Moreover, water-related disasters may increase in magnitude and frequency. In fact, between 1991 and 2000, 93 major disasters were recorded, resulting in billions of US$ in losses, most of which were in the agriculture sector. Sea level rise may have important implications on the sediment balance and may alter the profile of available land for production in the coastal areas. It is clear that climate change is a key sustainable development issue for Bangladesh (World Bank, 2000).

1.1 Objective of Study

The objective of this study is to examine the implications of climate change on food security in Bangladesh and to identify adaptation measures in the agriculture sector. This objective is achieved in the following ways. First, the most recent science available is used to characterize current climate and its potential changes. Second, country-specific survey and biophysical data is used to derive more realistic and accurate agricultural impact functions and simulations. A range of climate risks (i.e. warmer temperatures, higher carbon dioxide concentrations, changing characteristics of floods, droughts and potential sea level rise) is considered, to gain a more complete picture of potential agriculture impacts. Third, while estimating changes in production is important, this is only one dimension of food security considered here. Food security is dependent on several socio-economic variables including estimated future food requirements, income levels and commodity prices. Fourth, adaptation possibilities are identified for the sector. The framework established here can be used effectively to test such adaptation strategies.

1.2 Literature Review

Global changes in climate will have important implications for the economic productivity of the agriculture sector.The sector will be impacted by three primary water-related climate drivers. First, gradual changes in the distribution of precipitation and temperature will impact agriculture yield through possible changes in water availability and evaporative demands, tolerance of crops and incidence of pest attacks. Second, changes in the frequency and magnitude of extreme events (i.e. above-average floods, prolonged droughts) may result in additional shocks to the agriculture sector. The ability to recover from these short-term production losses and the impacts on long-term prospects is dependent on many macro and micro factors. Third, the prospects of sea level rise in the coastal areas will change the profile of available land for agriculture production and potentially the quality of groundwater used for irrigation. This is especially critical in land-constrained countries such as Bangladesh. Increases in carbon dioxide concentrations will also impact the rates of photosynthesis and respiration.

Much of the existing analysis on climate change impacts on the agriculture sector has primarily been focused on the first driver: changes in temperature and precipitation. Several global studies look at these impacts. For instance, Cline (2007) demonstrates using a range of methodologies and several global circulation models (GCMs) that agriculture production may decline in Bangladesh by as much as between 15 and 25 per cent. This study is dependent on global statistical production functions. Fischer et al (2002) derive similar estimates using an agro-ecological approach and the results from four global circulation models.

Several regional level studies also exist which show mixed responses to climate change. Lal et al (1998a, b, c) demonstrate that rice yields in neighboring India could decline by 5 per cent under a 2°C warming and CO2 doubling. Karim et al (1994) indicated a decrease in potential yields for aman and boro rice in Bangladesh when only a 2°C or 4°C temperature change is considered, but this decrease was nearly offset when the physiological effect of 555 parts per million (ppm) CO2 fertilization was taken into account. More recent results (Karim et al, 1998; Faisal and Parveen, 2003) show overall enhancement of potential rice yields but declines in potential wheat yields when 4°C temperature changes and 660ppm CO2 fertilization are simulated. The offset potential by carbon fertilization effects remains an area of active research (Long et al, 2005; IPCC, 2007b; Tubiello et al, 2007a, b; Hatfield et al, 2008; Ainsworth et al, 2008).

Although it is clear that floods can affect agriculture production significantly, little is known about the incremental future damages from more frequent extreme events or increased discharges. Economic damages have been calculated after several recent extraordinary flood events (e.g. almost US$700 million in agriculture losses were reported after floods in 2004). Hussain (1995) developed a methodology to incorporate yield losses from annual flooding into a crop simulation model. Sea level rise and salinity intrusion implications on the agriculture sector are even less understood. Habibullah et al (1998) calculated that the loss of food-grain due to soil salinity intrusion in the coastal districts is about 200,000 to 650,000 tons.

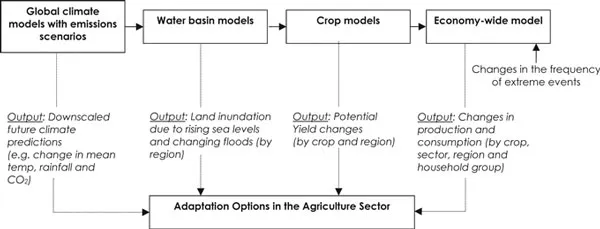

1.3 Integrated Modelling Methodology

The methodology employed in this study includes several stages. Climate and hydrologic models are used to produce future scenarios of climate and land inundation (from floods and sea level rise) for various GCMs and emissions scenarios. Then, these are linked to crop models to produce physical estimates of climate- and flood-affected potential crop yield changes for the three main rice varieties and wheat. These yield estimates are based on climate and biophysical data for 16 agro-climatic sub-regions in Bangladesh and provide a picture of the geographic distribution of climate change impacts on the agriculture sector. Then, the economic implications of these projected crop yield changes are assessed using a dynamic computable general equilibrium (CGE) model. The CGE model estimates their economy-wide implications, including changes in production and household consumption for different sectors, household groups and agro-climatic sub-regions in the country. Additional impacts from extreme events are also considered here.

As noted, multiple models are used in the study. These are among the best mathematical representations available of the physical and economic responses to a variety of exogenous changes (here, climate). However, like all modelling approaches, uncertainty exists as parameters may not be known with precision and functional forms may not be fully accurate. Thus, careful sensitivity analysis and an understanding and appreciation of the limitations of these models (identified throughout the study) are required. Further collection and analysis of critical input and output observations (e.g. climate data, farmlevel practices and irrigation constraints) will enhance this integrated framework methodology and future climate impact assessments.

Figure 1.1 Integrated modelling framework

1.4 Organization of Study

This study is organized into seven further chapters. Chapter 2 sets the historical context of climate risks in Bangladesh. Past experience with floods, droughts, sea level rise and observed trends is reviewed. Broader regional issues are also briefly discussed. Chapter 3 reviews the predicted future changes in precipitation and temperature (both at the country level and at the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna [GBM] river basin level). Chapter 4 presents an analysis on modelling the hydrology of future floods. This consists of both descriptions of a regional and national hydrologic models used and an analysis of the characteristics of the future floods both temporally and spatially. Among other aspects, the extent of the flood and the changes in the peak floods are analysed. A procedure for selecting a sub-set of global climate models is also presented as all available climate models could not be used. Chapter 5 describes the dynamic biophysical crop production models used. Here, various impacts of different climate risks (floods, droughts and sea level rise) on agriculture yields, focusing on rice and wheat, are incorporated. Chapter 6 describes a dynamic computable general equilibrium model used to evaluate the macro-economic and household welfare impacts of both climate variability and change-induced yield losses and gains. Chapter 7 presents potential adaptation options for the agricultural sector including unit costs that are currently being piloted in the field. Finally, in Chapter 8, the study concludes with general recommendations. Annexes provide additional information about using the crop models to test adaptation options and technical details of the CGE.

![]()

2

Vulnerability to Climate Risks

Box 2.1 Key Messages

- Despite the challenging physiography and extreme climate variability, Bangladesh has made significant progress towards achieving food security. Investments in surface and groundwater irrigation and the introduction of high yielding crop varieties have played and will continue to play a key role in this.

- The performance of the agriculture sector is heavily dependent on the characteristics of the annual flood. Regular flooding of various types has traditionally been beneficial. However, low frequency but high magnitude floods can have adverse impacts on rural livelihoods and production.

- The timing of the peaks on the three major river systems (Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna) is an important determinant of the overall magnitude of flooding.

- The economic toll of these extreme events can be significant, the order of billions of US dollars.

- Aman and aus rice are the primary drivers of declining overall production during major flood events, which is increasingly being compensated for by boro rice. Agriculture share of total GDP is declining and is likely to continue to do so, thus increasingly insulating the country from these shocks.

- Lean-season water availability, particularly in the northwest, can have consequences on agriculture production comparable to floods.

- In coastal areas, agriculture productivity is affected by the surface and groundwater salinity distribution.

- Future regional changes in the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna basin will play an important role in the overall timing and magnitude of water availability in Bangladesh.

Bangladesh is indeed a hydraulic civilization situated at the confluence of three great rivers – the Ganges, the Brahmaputra and the Meghna. Over 90 per cent of the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna (GBM) basin lies outside the boundaries of the country. The extensive floodplains at the confluence are the main physiographic feature of the country. The country is intersected by more than 200 rivers; there are 54 rivers that enter Bangladesh from India alone. Moreover, more than 80 per cent of the annual precipitation of the country occurs during the monsoon period between June and September. These hydro-meteorological characteristics of the three river basins are unique and make the country vulnerable to a range of climate risks, including severe flooding and periodic droughts.

Most of Bangladesh consists of extremely low land. The capital city of Dhaka (population of over 12 million) is about 225km from the coast but within 8m above mean sea level (MSL). Land elevation increases towards the northwest and reaches a height of about 90m above MSL (Plate 2.1). The highest areas are the hill tracts in the eastern and Chittagong regions. The lowest parts of the country are in the coastal areas. These areas are particularly vulnerable to sea level rise and tidal storm surges.

Bangladesh has a humid sub-tropical climate. The year can be divided into four seasons: the relatively dry and cool winter from December to February, the hot and humid summer from March to May, the southwest summer monsoon from June to September and the retreating monsoon from October to November. The southwest summer monsoon is the dominating hydrologic driver in the GBM basin. The Tibetan Plateau, the Great Indian Desert and adjoining areas of northern and central India heat up co...