Duino Elegies

- 104 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Duino Elegies

About this book

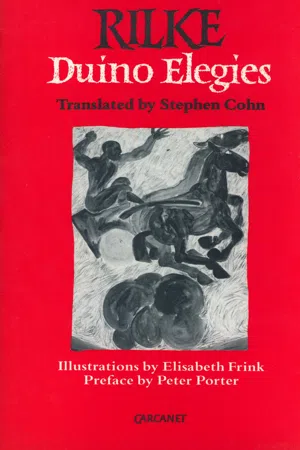

With all his contradictions, Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926) is one of the fathers of modern literature and the Duino Elegies one of its great monuments. Begun in 1912 but not completed until 1922, they are 'modern' in almost every sense the word has acquired; yet Rilke was by temperament anti-modern, a snob and a romantic. He was devoted to the three A's: Architecture, Agriculture, Aristocracy. The Duino Elegies aroused real excitement among English readers when the now-dated Leishman/Spender versions first appeared in the 1930s. Stephen Cohn, the distinguished artist and teacher, has worked for over three years to complete this outstanding new translation. Peter Porter writes: 'Your translation must have grandeur, essential size in its component parts, and speed to catch the marvellous twists of Rilke's imagination.' He adds, 'Cohn has met all these requirements.' These versions show a rare empathy with the originals and an instinct for the right diction and cadence. They are, says Porter, 'the most flowing and organic I have read.'

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Notes on the Translation

Die erste Elegie

Rilke’s enthusiasm for parting, loss, death and bereavement is critical to his particular existentialist credo.

Die zweite Elegie

Here, and again at the beginning of the Third Elegy, Rilke succeeds in offering, at one and the same time, chaste metaphor and explicit sexual imagery; and in allowing readers their own choice of interpretation.

Die dritte Elegie

All action and drive are given to the Lord of Desire himself: the role of the young woman is entirely subordinate.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Dedication

- Preface

- Introduction

- Die erste Elegie

- The First Elegy

- Die zweite Elegie

- The Second Elegy

- Die dritte Elegie

- The Third Elegy

- Die vierte Elegie

- The Fourth Elegy

- Die fünfte Elegie

- The Fifth Elegy

- Die sechste Elegie

- The Sixth Elegy

- Die siebente Elegie

- The Seventh Elegy

- Die achte Elegie

- The Eighth Elegy

- Die neunte Elegie

- The Ninth Elegy

- Die zehnte Elegie

- The Tenth Elegy

- Notes

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app