- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

An Introduction to Cultural Ecology

About this book

This contemporary introduction to the principles and research base of cultural ecology is the ideal textbook for advanced undergraduate and beginning graduate courses that deal with the intersection of humans and the environment in traditional societies. After introducing the basic principles of cultural anthropology, environmental studies, and human biological adaptations to the environment, the book provides a thorough discussion of the history of, and theoretical basis behind, cultural ecology. The bulk of the book outlines the broad economic strategies used by traditional cultures: hunting/gathering, horticulture, pastoralism, and agriculture. Fully explicated with cases, illustrations, and charts on topics as diverse as salmon ceremonies among Northwest Indians, contemporary Maya agriculture, and the sacred groves in southern China, this book gives a global view of these strategies. An important emphasis in this text is on the nature of contemporary ecological issues, how peoples worldwide adapt to them, and what the Western world can learn from their experiences. A perfect text for courses in anthropology, environmental studies, and sociology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access An Introduction to Cultural Ecology by Mark Q. Sutton,E. N. Anderson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

In the four or five million years since their development, humans have colonized practically every terrestrial environment on the planet. Humans everywhere are virtually the same biologically but have been able to adapt to the enormous environmental diversity of Earth through culture, an immensely flexible and adaptive mechanism that other animals lack. Thus, humans have been a very successful species. Human activity has a wide range of impacts on the environment, however, from exceedingly minor to catastrophic. Now, human activities are having huge impacts on the very environment on which we humans depend, ultimately threatening our own existence. Understanding and dealing with these challenges is a daunting, but essential, task.

People in Western societies tend to hold the view that humans are separate from the environment, above it in some way. This view can be traced back to the Bible, which tells us the world (the environment) was created first, and then “man”—an entity separate from and superior to nature—was created and given the task of subduing nature (Gen. 1:28; also see Wilson 1967:1205). Other cultures have similar stories. Western philosophy continues to include the view that it is the goal and mission of people to “conquer” nature. Thus, many people today still believe that humans are not participants in the environment but that we must overcome it and bend it to our will. This conviction continues to permeate Western thought and action; consider, for example, the way we strive to separate ourselves from our natural surroundings by creating closed environments, including our homes, offices, and cars.

One could argue that many traditional societies (non-Western, non-industrialized cultures) do not hold this Western view and that they are somehow “ecologists” living in harmony with their environment (e.g., White 1997; but also see Krech 1999). It is true that the activities of many societies have less impact on the environment than those of others, and it is also true that some of these groups hold a more ecologically friendly philosophy of life than Westerners as a whole do. However, it has also been argued that traditional cultures generally have less impact on the environment only because their technology is less complex and their populations smaller. Given the right conditions and incentives, the argument goes, they would do as Westerners do. In support of this argument, one can point to the destruction of the habitat on Easter Island (e.g., Diamond 1995), the deforestation of most of Europe during the Neolithic era, and the Norse degradation of the Northern Islands (McGovern et al. 1988), among other examples.

Fortunately, traditional people can in general be trusted to take care of their resources, not out of fuzzy, New-Age love for Mother Earth, but out of solid, hardheaded good sense, often shored up by traditional religion and morality (Anderson 1996; Berkes 1999; Lentz 2000). Biologists are beginning to realize this truth. Kent Redford, who coined the sarcastic (and racist) term “the ecologically noble savage” (Redford 1990; see the superb refutation of that article by Lopez 1992), has since repented and now takes a more balanced and reasonable position (Redford and Mansour 1996; Sponsel 2001). We must first of all recognize that humans and their cultures are an integral part of the matrix of the environment and are not separate from it in either cause or effect. Human activity affects the environment, which is then altered, in turn affecting human activities, and so forth. The shape and form of the environment are dependent on its history, a history that includes humans. Yet it is also important to realize that humans are not just another animal running around the landscape. Humans are self-aware, cooperative, technological, and highly social. This unique combination does separate humans from other organisms, making their interactions with the environment very complex and fascinating.

WHAT IS CULTURAL ECOLOGY?

Ecology is the study of the interaction between living things and their environment. Human ecology is more specific, being the study of the relationships and interactions between humans, their biology, their cultures, and their physical environments. In the 1950s the overall field was known as cultural ecology, but it is now more commonly referred to as human ecology (following Human Ecology, the leading journal in the field). Human ecology is sometimes referred to by other names, including ecological anthropology (which may include aspects of biological anthropology), culture and environment, and even (still) cultural ecology.

Several comprehensive treatments of the field are available. Most impressive is Human Adaptive Strategies: Ecology, Culture, and Politics (Bates 1998). The title suggests a grounding in the new knowledge and also the way Bates integrates the field around the concepts of adaptation and strategizing. In addition, Bates and Susan Lees, longtime editors of Human Ecology, have produced a collection of articles from that journal, Case Studies in Human Ecology (1996). Patricia Townsend has brought out a brief but extremely well-targeted overview, Environmental Anthropology (2000), which covers basically the same ground from a very similar point of view but at an entry level.

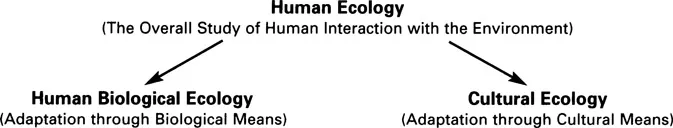

Human ecologists study many aspects of culture and environment, including how and why cultures do what they do to solve their subsistence problems, how groups of people understand their environment, and how they share their knowledge of the environment. The broad field of human ecology includes two major subdivisions (see fig. 1.1). Human biological ecology is the study of the biological aspect of the human/environment relationship, and cultural ecology is the study of the ways in which culture is used by people to adapt to their environment.

FIGURE 1.1 The general relationship of the subdivisions within human ecology.

The primary focus of this book is the subdivision of cultural ecology, which encompasses everything from pet dogs to the Fall of Rome, an ecological catastrophe caused in part by misuse of resources (see, e.g., Ponting 1991). This book examines, among other things, salmon ceremonies among Northwest Coast Indians, Maya agriculture today and in the past, sacred groves in southern China, and the use of various foods. Insects, for example, are an abundant and nutritious source of food, yet many cultures consider them pests. Some of the very cultures that loathe insects see shrimps and lobsters as delicacies, although all three are very similar biologically. Why is there such a cultural difference in the way they are regarded?

Consider a food question that is far more serious. Significant deforestation has resulted from the creation of cattle pasture. As much as Americans may feel they depend on their hamburgers, beef is really a luxury item, producing relatively little protein at huge expense. To produce it, millions of acres of land that were once covered in forest or in farmland growing food for local people have been converted into pasture. The devastation to wildlife and biological diversity is bad enough; the impoverishment, and frequently the starvation, of local people may be considered even more serious. Thus, cultural beliefs about food can dramatically affect the world environment.

The study of the relationships between culture and environment is not just academic; it is vital, not simply because it is interesting, but because it offers understanding of and possible solutions to important contemporary problems. Issues of deforestation (e.g., Anderson 1990), loss of species (e.g., Blaustein and Wake 1995), food scarcity (Brown 1994, 1996), and soil loss (Pimentel et al. 1995) are on the minds of many and are beginning to be addressed by human ecologists. (For general discussions of human impact on the environment, see Goudie 1994; Ehrlich and Ehrlich 1996; Meyer 1996; Redman 1999; and Molnar and Molnar 2000, among others.) Some of these issues reflect overexploitation of resources and require conservation measures. Such measures may threaten certain short-term economic activities, such as unrestricted logging, and many leaders launch verbal, and sometimes even physical, attacks on conservationists (see Helvarg 1994) to protect their short-term interests.

Cultural ecologists record other traditional and local knowledge that is of value to the wider world. Thousands of useful drugs used by Westerners have been derived from traditional medicines, and more are being tested and developed almost daily. Ancient crops of the Andes and Tibet, such as potatoes and barley, respectively, are becoming important worldwide. Long-established land management techniques used in Indonesia and Guatemala—multilayered and multicropped orchard gardens, for example—are inspiring changes in the greater arena. The accumulated cultural knowledge of billions of people over tens of thousands of years is available and is a tremendous resource for our resource-short world.

ANTHROPOLOGY

Human ecology is generally included within the discipline of anthropology, the study of human beings. Anthropology includes the study of human biology, language, prehistory, religion, social structure, economics, evolution, and anything else that applies to people. Thus, anthropology is a very broad discipline, holistic in its approach and comparative, or cross-cultural, in its analyses. Anthropologists generally concentrate their work on small-scale cultures and tend to have considerable personal contact with the people of those cultures.

Culture, learned and shared behavior in humans, is the fundamental element that sets humans apart from the other animals. The vast complexities of human behavior are largely related to culture and, to a lesser extent, biology. Culture is largely transmitted through language, which, as far as we know, is unique to humans. In addition, every person belongs to a culture, a group of people who share the same basic pattern of learned behavior—the same values, views, language, and identity. Each culture holds an identity unto itself, such as the Cheyenne, the Germans, or the Yanomamo, and its members recognize that they are different from other cultures.

Anthropologists traditionally follow a set of basic beliefs in their study of other cultures. First, they recognize that all cultures are at least a bit ethnocentric: in other words, people believe their culture is superior to others (although many envy the more rich or powerful). Americans tend to view non-Americans as being inferior, less cultured, or backward. Germans have the same view of non-Germans, as do the Chinese of non-Chinese. In fact, every culture holds this view; it is a normal part of the self-identification process. However, ethnocentrism has often been used to rationalize mistreatment of peoples. Virtually all colonial powers exploited native populations in the belief that they were inferior, and the colonizers used this belief to justify enslaving and murdering the natives. In North America, the natives were considered “savages” who were “in the way” of “civilization.” The Native Americans were thus moved, incarcerated, or killed with government approval. A similar situation currently exists in a number of Third World countries attempting to “develop.”

Anthropologists are usually from a culture other than the one being studied. Thus, researchers often view the culture through the lens of their own culture, in essence an outsider’s view. One’s perspective, whether insider or outsider, influences what is observed and ultimately what can be learned. Anthropologists deal with this problem as best they can.

A basic conviction in anthropology is cultural relativism, the belief that cultures and cultural practices should not be judged. This term has been misunderstood to imply that anthropologists approve of anything practiced in any culture. More correctly, it means that anthropologists study cultures without trying to show that one is “better” than another and without trying to impose their culture on other people. This relativity is methodological, not moral. Indeed, anthropologists have traditionally taken a very strong stand against genocide and “culturocide,” or forcing people to give up their culture against their will. Anthropologists attempt to avoid being ethnocentric and believe that all people and cultures are valid; that people have the right to exist, to have their own culture and practices, and to speak their own language; and that individuals have fundamental human rights (Nagengast and Turner 1997; Merry 2003).

Anthropology can be divided into many subdisciplines, perhaps dozens, depending on how it is defined and who is defining it. Here we follow a traditional division of the field into four subdisciplines: cultural anthropology, biological (or physical) anthropology, anthropological linguistics, and archaeology.

Cultural Anthropology

Cultural anthropology, sometimes called social or sociocultural anthropology, is the study of existing peoples and cultures. Cultural anthropologists conduct two major types of studies: ethnography, the study of a particular group at a particular time, and ethnology, the comparative study of culture. Cultural anthropologists strive to learn everything they can about a culture, such as kinship systems, marriage rules, economics, language, and politics. Cultural anthropologists generally live with a group under study, observe and record its members’ activities and behavior, and ask people questions. Cultural anthropologists can sometimes even participate in, and so can better record, community activities. As such, cultural anthropologists can get a rich, though still incomplete, record of a group. The weakness of cultural anthropology is that, despite the detail of the information, little time depth is reflected, making change difficult to detect.

Biological Anthropology

Biological anthropology is the study of the biology and evolution of people, as well as the study of the biology, evolution, and behavior of nonhuman primates and other animals for clues to understanding humans. While humans are all very similar biologically, some differences between groups do exist. These differences may take a variety of forms, including stature, blood type, and adaptations to cold or high altitude. An understanding of past human biology can help us understand evolution and suggest relationships with other populations, such as intermarriage and/or migration, changes in past environment, and changes in subsistence.

Anthropological Linguistics

Anthropological linguistics is the study of human language. Its scope includes the historical relationships between languages, common “ancestors” of languages and language groups, syntax, and meaning. Cultural anthropologists are interested in linguistics because a great deal about a particular culture can be learned by looking at its language. Archaeologists are interested in linguistics, especially historical linguistics, because languages (and cultures) can be traced back in time.

Archaeology

Archaeology is the study of the human past. There is some overlap between archaeology and cultural anthropology, as archaeologists want to learn the same things about past cultures that cultural anthropologists do about living ones. Archaeologists often study the present as well, either to find clues for interpreting the past or to investigate present-day problems by using archaeological methods.

The major differences between archaeology and cultural anthropology are in the available data and the methods used to obtain those data. The material remains with which archaeologists work are limited, partly due to excavation techniques; as a result, archaeologists do not obtain the entire picture of a past culture. However, archaeologists are able to detect change over long periods of time, can identify broad trends, and can examine transitions, such as the change of some cultures from hunting and gathering to agriculture. In addition, an archaeologist can detect the traces of behavior that a cultural ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Fundamentals of Ecology

- 3 Human Biological Ecology

- 4 Cultural Ecology

- 5 Hunting and Gathering

- 6 The Origins of Food Production

- 7 Horticulture

- 8 Pastoralism

- 9 Intensive Agriculture

- 10 Current Issues and Problems

- Glossary

- References

- Index

- About the Authors