eBook - ePub

Care of the Dying Patient

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Care of the Dying Patient

About this book

Although the need for improved care for dying patients is widely recognized and frequently discussed, few books address the needs of the physicians, nurses, social workers, therapists, hospice team members, and pastoral counselors involved in care. Care of the Dying Patient contains material not found in other sources, offering advice and solutions to anyone—professional caregiver or family member—confronted with incurable illness and death. Its authors have lectured and published extensively on care of the dying patient and here review a wide range of topics to show that relief of physical suffering is not the only concern in providing care.

This collection encompasses diverse aspects of end-of-life care across multiple disciplines, offering a broad perspective on such central issues as control of pain and other symptoms, spirituality, the needs of caregivers, and special concerns regarding the elderly. In its pages, readers will find out how to:

While physicians have the ability to treat disease, they also help to determine the time and place of death, and they must recognize that end-of-life choices are made more complex than ever before by advances in medicine and at the same time increasingly important. Care of the Dying Patient addresses some of the challenges frequently confronted in terminal care and points the way toward a more compassionate way of death.

This collection encompasses diverse aspects of end-of-life care across multiple disciplines, offering a broad perspective on such central issues as control of pain and other symptoms, spirituality, the needs of caregivers, and special concerns regarding the elderly. In its pages, readers will find out how to:

- effectively utilize palliative-care services and activate timely referral to hospice,

- arrange for care that takes into account patients' cultural beliefs, and

- respond to spiritual and psychological distress, including the loss of hope that often overshadows physical suffering.

While physicians have the ability to treat disease, they also help to determine the time and place of death, and they must recognize that end-of-life choices are made more complex than ever before by advances in medicine and at the same time increasingly important. Care of the Dying Patient addresses some of the challenges frequently confronted in terminal care and points the way toward a more compassionate way of death.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Care of the Dying Patient by David A. Fleming, John C. Hagan, David A. Fleming,John C. Hagan,John C. Hagan, III in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Caregiving. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Control of Suffering

1

Pain Management at the End of Life

Pain is a universal aspect of life and part of our sensory experience. It is necessary and adaptive. At the same time, it is a form of suffering that can affect the duration and detract from the quality of human life. Currently, there are both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic tools that allow us to modify pain in such a way as to minimize its impact on quality of life. This is a miracle of modern medicine. Still, around the world as well as in the United States, most pain sufferers are inadequately treated, for a variety of reasons.1 In other countries, the necessary medications may not be available.2 In the United States, the barriers to adequate pain modification include regulatory burdens, cost, myths about pain and pain medicines, and lack of education for the public and for medical professionals.3

Significant pain is present in the majority of patients dying of chronic diseases such as cancer, heart disease, lung disease, and diabetes.4 End-of-life care entails treating patients with these chronic diseases when the diseases are in their final phase, with the focus on bringing about relief of suffering and aggressively treating symptoms caused by the diseases. The common complaint of pain at the end of life is usually eminently treatable now, yet most patients remain undertreated.5 Here I will describe the problem of pain at the end of life and then show a way to optimally manage pain in this vulnerable population.

The Problem: Pain and Its Pathophysiology

Pain, one of many forms of suffering, is common at the end of life and is usually accompanied by a plethora of other symptoms, including dyspnea, nausea, confusion, anxiety, and depression.6 Pain seems to be the predominant symptom and also the most feared form of suffering.7 Pain at the end of life is protean and complicated. No two patients are alike in terms of the pathophysiology of their pain complaints or the psychosocial contexts of their pain. Pain at the end of life is undertreated, which is completely preventable. There is an ethical obligation in medicine and nursing to relieve suffering, and it is this directive that should lead physicians and other providers, as well as society in general, to bring down barriers and optimize pain management throughout life, but particularly at the end of life.

The pathophysiology of pain is complex, with new scientific discoveries in this area occurring frequently. I will now explain the basic concepts of pain pathophysiology so as to inform the rationale for optimal pain-management strategies. Nociception, the most upstream signal in pain physiology, occurs when tissue damage results in the stimulation of peripheral neuroreceptors in tissues, which, in turn, transmit a signal to a peripheral nerve. Transmission is the traversing of a pain signal from the nociceptor to the peripheral nerve to the spinal cord to the brain stem to the midbrain to the sensory cortex to the association cortex. Next is modulation, when, at least at the levels from the spinal cord and above, descending and local signals serve to either dampen or accentuate the ascending pain signals from the periphery. After modulation comes cognition, the final, summed subjective sensation of pain and modifying influences as experienced by the patient. Finally, expression is the communication of this cognition to others, verbally or nonverbally. Although simplistic, this schema allows us to get from a painful site in the body to the point where the person suffering the pain tells the provider about the pain in the context of his or her life and illness, and also shows us the levels at which any intervention might have an impact upon the pain.

Assessment and Therapy

Thorough assessment of pain is absolutely vital in order to treat it optimally and manage the disease causing it appropriately. This is true for diseases in the end-of-life phase as well as eminently curable conditions. Important factors in the assessment of pain include determining the following: location—subjective and anatomic description of where the pain is situated; chronicity—the duration of the pain complaint; temporal pattern—how the pain changes over time; severity—the intensity of the pain complaint, often measured from 0 to 10 (ordinal scale)8 or on a visual analog scale;9 character— how the pain is described, as sharp, dull, stabbing, burning, etc.; and associated findings—at the end of life, many other findings may be present, including dyspnea, cachexia, fever, depression, etc. A comprehensive approach to treating pain, one that takes into account both its characteristics and the results of the workup indicating possible etiology and/or a unique pathophysiology, is most likely to be successful.

Assessment, workup, and therapy sometimes occur nearly simultaneously in the real-life situation, but in general, an initial assessment and treatment is usually followed as soon as possible by a thorough workup in the outpatient or inpatient setting. The workup includes a physical examination—a good general examination with special attention to the neurologic and musculoskeletal findings; laboratory examination—judicious use of laboratory tests to confirm or refute suspected conditions causing the pain complaint (for example, infection or bone metastasis); radiographic evaluation—targeted radiographs including plain films, computed tomography, ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, and even positron-emission tomography; and other tests—for example, biopsies would be required to confirm a diagnosis of primary cancer or recurrence, and pulmonary-function tests or echocardiogram would address the severity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or congestive heart failure at a given point in time. This evaluation narrows the possible causes of pain, which are usually still numerous in dying patients, and allows for targeted therapeutics.

Therapy should occur simultaneously with the workup process, not upon completion of the workup. Either the outpatient or inpatient setting may be appropriate for evaluation and management of pain, depending upon the severity of the symptoms and the ease of control. The primary physician, nurse, psychosocial professional, and consultants should be involved as indicated from the beginning and should have the ability to communicate on a daily and preferably in-person basis. Through the workup and therapy, the target of the efforts should be the pain experienced and described by the patient.

Physicians and nurses both tend to focus heavily on the pharmacologic management of pain, but it is important to point out that there are multiple other therapeutic modalities that can impact pain in a positive way, and that the right mix of modalities for a successful therapeutic plan will be different for each patient. In addition to pharmacologic agents, other modalities include surgical intervention, other interventional techniques, palliative or radical radiotherapy, physiatry, massage, and electromagnetic therapy (for example, ultrasound or electrical stimulation).

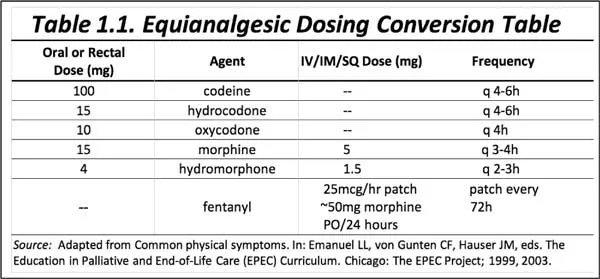

The principles of pharmacologic therapy for pain are well-established and have not changed dramatically in over three decades. Unfortunately, these principles are not being applied uniformly or effectively even in the United States. The World Health Organization formulated an analgesic-ladder concept in 1986 to serve as a guide to practitioners around the world regarding rational, effective use of non-opiate and opiate analgesics.10 Opiates are the mainstay of pharmacologic therapy for pain at the end of life because they are safe, effective, and easy to use from a pharmacologic point of view. There is no maximum dose of any pure opiate agonist. These medications have several drawbacks, including regulatory constraints, limited supplies (in some countries), and the real but uncommon problems of abuse, diversion, and addiction. Opiates come in weak, moderate, and strong agents; single-agent versus combination products; longacting versus short-acting formulations; and in forms for a variety of intended routes, including oral tablets/capsules, oral liquids, sublingual or transmucosal oral liquid or lozenge preparations, transdermal patches, suppositories, and solutions intended for the intravenous, subcutaneous, or intramuscular route. Most patients with chronic pain including at the end of life will do best with both a long-acting opiate formulation to prevent most pain and a short-acting opiate agent to treat episodic or breakthrough pain.11 It is relatively simple to choose an appropriate agent(s), dose, route, and schedule, and most of the time, with follow-up and adjustment as needed, this plan of treatment will be successful. If not, switching to another type of opiate often works. This is called opiate rotation, and it is successful about 50 percent of the time.12 In changing from one opiate agent to another, or from one route to another with the same or a different agent, an equianalgesic dosing table is quite helpful (see table 1.1).

In addition to opiates, other agents can have a direct or indirect effect on pain sensation or transmission. Traditionally, these other medications are called co-analgesics if they have analgesic properties on their own and adjuvant medications if they do not. The lines between these medications are becoming blurred as we learn more about their clinical and pharmacologic properties. Depending upon the type of pain—nociceptive, neuropathic, inflammatory, central, etc.—these other agents may add a great deal to what can be done with an opiate alone. In fact, on the WHO analgesic ladder, the first step is the use of acetaminophen or aspirin (or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]) alone, without an opiate.13 These weak analgesics can control mild pain, even at the end of life, in many patients. Other categories of adjuvants or co-analgesic medications include anti-inflammatory agents (corticosteroids and NSAIDs), true adjuvants/neuromodulators (tricyclic antidepressants, anticonvulsants), psychiatric agents (antidepressants, anxiolytics, neuroleptics), and topical agents (lidocaine lotion or patches, capsaicin cream). Other medications are commonly utilized to minimize side effects from opiates and similar medications; these include stool softeners, laxatives, antiemetics, antacid medications, psychostimulants, and sedatives.

Adequate control of pain at the end of life requires aggressive application of multimodality therapy as needed. Of course, the most simple and straightforward plan of care possible would be the preferred one, yet many patients at the end of life truly require multiple complementary medications and other therapies. The plan should be as aggressive and multifaceted as is needed to achieve the goal of reasonable comfort or minimal suffering, along with maximal cognitive and physical function, in the context of the underlying disease process. Rapid, frequent reassessment is vital. Reassessment includes serial pain-scale measurements over time, repeat physician visits with physical exams, appropriate laboratory tests and radiographs, nurse reassessments, and analysis of home health and hospice evaluations. Each assessment should be followed by appropriate alterations to the plan of care, along with updated education of the patient and family caregiver. Changes in old symptoms or the appearance of new ones warrants more thorough investigations to look for treatable etiologies of the new symptoms. Methods of controlling the side effects of the opiates and other effective medications should also be reassessed along the way and changed accordingly.

Conclusion

The problem of undertreated pain at the end of life is still a major challenge for health-care providers. In the United States, all of the resources to solve this problem are at hand. For the vast majority of patients, the full and judicious use of these resources will result in a satisfactory to excellent outcome in terms of control of pain and related symptoms. In only a small percentage of patients will refractory symptoms remain or interventional procedures be required. Still, financial, regulatory, and attitudinal constraints remain as the main impediments to reducing the burden of pain at the end of life. Disseminating knowledge and effecting change in attitudes and policies must accompany the increased application of modern pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies in a multidisciplinary setting. Although new agents are on the horizon, their absence should not be an impediment to success in this arena today.

Notes

1. Von Roenn JH, Cleeland CS, Gonin R, et al. Physician attitudes and practice in cancer pain management: A survey from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:121–126.

2. World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief and palliative care. Technical Report Series 804. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1990.

3. American Academy of Pain Medicine and the American Pain Society. Consensus statement. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:68.

4. Ferrell BR, Ferrell BA. Pain in the elderly: A report of the task force on pain in the elderly of the International Association for the Study of Pain. Seattle:...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part 1: Control of Suffering

- Part 2: The Needs of Special Populations

- Part 3: Psychological and Spiritual Needs

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index