1 Tempting two fates

The theoretical foundations for understanding Central Eurasian transitions

Christoph H. Stefes and Amanda E. Wooden

Wise Providence gave our perception

The choice between two different fates:

Either blind hope and agitation,

Or hopelessness and deadly calm

Two Fates, Evgeny Baratynsky

The poet Evgeny Baratynsky wrote of the two fates confronted by the young and ardent and the old and measured, and surmised about the choice each group will make. At first glance, the countries of the Caucasus and Central Asia have in recent history faced a seemingly similar choice of agitated or calm political fates. These dichotomous political and policy choices are what scholars have referred to as the choice between pluralism and authoritarianism, capitalism and socialism, or conflict and stability. However, the outcomes might not be so dualistically simple, although these simplified concepts have dominated popular press and public notions of choices made by decision-makers.

In this book, we discuss the causes and consequences of this seemingly dichotomous transition from the Soviet period. The introductory chapter begins by summarizing the main theoretical debates about the study of politics in Central Eurasia. Throughout the book, we also utilize this popular and simplified notion of a dichotomous transition (successful or unsuccessful) to highlight what is varied and nonlinear about the process of political change. We argue that it is important to understand the great many policy outcomes possible given multiple influences, varied starting points, and changing contexts. In clearly disaggregating these influences and identifying the similarities and dissimilarities across the region, using the simplifying concept of a bidirectional transitional continuum and through a multi-country comparative approach, we are able to ascertain a possible set of varied outcomes.

In order to frame the comparisons made in the chapters of this book, this introduction provides the foundational discussion of the relevant literature on transitions regarding the study of institutions, distribution of power, disputes, actors and their socio-economic policy considerations. Each chapter fits into this theoretical overview and seeks to answer the questions derived from it. Is there a path between Baratynsky’s prophesied outcomes that the countries of the Caucasus and Central Asia are pursuing? Are there easily identifiable dichotomies in political context and policy approaches? By focusing on hypothesized dichotomies are non-dichotomous outcomes identifiable? What are the variations in combinations that each chapter identifies or ignores? We conclude this chapter by providing an overview of the layout for this book.

The purpose and scope of this book

The overarching goals of this book are to reveal and compare policy outcomes in Central Eurasia and move beyond overly simplified conceptions and evaluations of political change in the region. The importance of doing so is framed in this introduction, by highlighting both the valuable contributions and the theoretical failings of much work on the region. We seek to meet this goal given the limited comparative analysis done of both context and outcomes of government action across issues of politics, economics, society, and the environment. None of these elements operates in a vacuum, and thus it is important to separate out the factors of transition. Chapter 2 allows insight into the process of studying the region, the questions that frame the research scholars’ conduct, and the methodologies chosen (and not chosen) to study the politics of Central Eurasia. This volume allows the student of Central Eurasia to gain an overview of approaches to studying the politics of the region and an aggregated explanation of the convergent and divergent paths Central Eurasian countries have taken.

An important question for defining the scope of this book has dominated methodological and professional association identity debates in the last decade and a half: what is this region “Central Eurasia” anyway? As defined in this volume, “Central Eurasia” includes the three non-Russian former Soviet countries of the South Caucasus (Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia) and the five former Soviet countries of Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan). We limit our discussion to former Soviet countries for methodological reasons, applying a most-similar system design. Although we do not ignore the varied pre-Soviet and Soviet histories of these countries, we identify the main components of comparability that make these countries most similar within the post-Soviet space. This comparability is due to inclusion of this “southern tier” into the Russian colonial sphere in the nineteenth century (in contrast to the Baltic countries) and formalized inclusion in the space of the Soviet Union in the early twentieth century, and as a location for colonial resource exploitation and collectivization. These Russian and Soviet era similarities remain important as a basis for understanding post-Soviet identity and governance. Therefore, we exclude from the “Central Eurasian” region as defined here the Northern Caucasus and Central Asian parts of Russia and the non-post-Soviet countries or provinces within the broader geographical, non-political concept of Central Asia, such as Iran, Afghanistan, and China.1 Studying Central Asia and the Caucasus comparatively has gained acceptance as a broadly defined region separate from other parts of the former Soviet Union, though there is still debate over the boundaries of this region and what the region shall mean in the future.

Identifying in this chapter most similar political and socio-economic aspects, we are able to focus on the dissimilarities and variations among and within these societies. Therefore, focusing on the eight former Soviet, non-Russian countries of “Central Eurasia,” we proceed in this chapter to systematically evaluate the theoretical foundations of scholarship about political, socioeconomic, and environmental transitions from 1991–2008 and the policy problems identified by these evaluations.

Transitions from communism in Central Eurasia

Most scholars who analyze the changes that have taken place in Central Eurasia since 1991 avoid using the concept “transition” in any closed-ended way. A closed-ended conception implies that post-Soviet countries inevitably and continuously move from communism to a predetermined endpoint (Gans-Morse 2004). Following the modernization paradigm, this endpoint would be a liberal democratic and capitalist regime. Alternatively, instead of moving towards democracy and free markets the eight states of Central Eurasia might return to a time before communist rule when feudal institutions structured the societies in the South Caucasus and Central Asia (Burawoy and Verdery 1999; Verdery 1996).

The editors and contributors of this volume do not conceptualize transition in any teleological (i.e. closed-ended) way. They do not share the assessment that the Central Eurasian states are on the preordained march towards a Western-style political and socio-economic regime or a feudal system. Instead, the authors concur with Pauline Jones Luong and her collaborators when they argue that post-Soviet Central Asia, as it recreates disintegrated state and market structures, reveals a peculiar combination of pre-Soviet, Soviet, and entirely new institutions as well as formal and informal practices and norms (Jones Luong 2004). Thus, unique political contexts are emerging in Central Eurasia.

In short, when we use the concept “transition” we mean “transition from communism” without any preconceived notion of a possible endpoint. Neither do we assume that these eight countries will experience uniform transitions. Although these transitions might be grouped for analytical purposes, the uniqueness of each transition is difficult to ignore.

Explaining political transitions

Despite the uniqueness of transitions in Central Eurasia, all eight countries have one attribute (or the absence thereof) in common. Almost 20 years after the fall of Soviet authoritarianism, liberal democratic regimes remain conspicuously absent. State institutions that protect and advance political rights and civil liberties have not emerged to fill the void that the collapse of Soviet rule left. Yet beyond this negatively defined attribute, differences in regime type soon become apparent. Given the level of state repression and the absence of political competition, some regimes are plainly authoritarian. Other Central Eurasian states, however, can be called semi-democratic or at least semi-authoritarian insofar as some political competition takes place and violations of basic human rights are not as frequent as in the former group. To avoid a definite verdict about the “democraticness” of these regimes, the concept of hybrid regime was introduced to cover the gray area between (liberal) democratic and authoritarian rule (Bunce 2001; Merkel and Croissant 2000). In addition, a comparison over time shows that some regimes have not changed much or at all since the early 1990s while others, especially the hybrid regimes, saw political turmoil and social unrest.

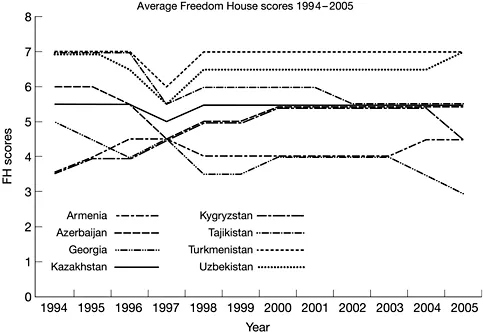

Going beyond idiosyncratic analyses of the political transitions in Central Eurasia with the goal of developing general theories requires us to classify Central Eurasia’s regimes in different categories. Thereafter, we should not only systematically compare analytical groups but also the individual cases within each group, highlighting differences among otherwise similar countries (Sartori 1970). An analysis of Freedom House’s Freedom in the World Index (Freedom House, various years) allows for a broad distinction between stable authoritarian regimes (“not free” according to Freedom House) and those that have been hybrid regimes (“partly free”) either throughout or at least most of the post-Soviet period. The first group consists of Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Tajikistan. Georgia, Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, and Azerbaijan belong to the second group (Figure 1.1).

Politically, the collapse of Soviet rule meant little for the countries in the first group. Authoritarian rule has remained in place and elite continuity is prevalent. For analysts of political change the obvious questions to ask therefore are: Why has authoritarian rule persisted in the first group but not in the second? How has it been possible for the Soviet elite to maintain their grip on power?

Within this group of stable authoritarian regimes, significant differences exist. For instance, while Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan are highly repressive regimes in which incarceration and torture of political opponents is commonplace, the authoritarian leaders of Tajikistan and Kazakhstan rely less on open repression to stay in power. This finding invites questions regarding the different modes of authoritarian rule, under which circumstances they are successful, and why they are chosen in the first place.

As for the group of hybrid regimes, notable deviations are also noticeable, especially when comparing these countries over time. In the mid-1990s, all four countries had witnessed political liberalization and therefore seemed to be on track towards liberal democratic rule. Liberalization was reversed and oppression of political rights and civil liberties became widespread in the latter half of the 1990s. In Azerbaijan and Armenia, increasing “authoritarianization” has so far remained without any political consequences. Yet in Georgia and Kyrgyzstan popular protests removed from power increasingly illiberal presidents—Eduard Shevardnadze during the Rose Revolution (2003) and Askar Akayev during the Tulip Revolution (2005), respectively. We might therefore ask why increasing repression has turned out to be a successful strategy for the leaders of Armenia and Azerbaijan but not for their counterparts in Georgia and Kyrgyzstan.

Figure 1.1 Political developments in Central Eurasia.

Source: Freedom House

Finally, beyond questions related to regime stability and change, another interesting puzzle concerns the interethnic relations within the eight Central Eurasian countries. While the South Caucasus has seen violent and protracted ethnic conflicts, relations between the various ethnic groups of Central Asia have been considerably more amicable. As Julie George in her chapter points out, in the wake of the breakup of the Soviet Union many scholars expected the opposite. Which factors then caused the outbreak of violent ethnic conflict in Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan? Moreover, were these factors simply absent in Central Asia or were they compensated by other factors that fostered interethnic accommodation? These questions obviously have increased relevance as the August 2008 war between Georgia, Russia, and South Ossetia demonstrates.

In the section that follows, we address the above questions by surveying leading studies of political transitions in Central Eurasia. This overview also allows us to discuss contributors’ chapters within the context of the scholarship on the region. In doing so, we separate between bottom-up approaches, which identify forces of political change mainly within society, and top-down approaches, which see the state and the political elite as the major agents of political development in the region. We further separate between approaches that focus exclusively on domestic forces and those that recognize the impact of international factors on the political processes in the region.

Among those who ...