![]()

1

Introduction

Lesbian Discourses, Lesbian Texts

My life firts in with the decades quite well, because I was born at the beginning of a decade.

(interview with Vivienne Pearson)1

My first lesbian text was a slim paperback called Women Without Men written by a certain Jessica Simmons. Published in 1970, it must have been one of the last of the lesbian pulp novels so popular in the 1950s and 1960s, and accordingly, its cast is for the better part ailed by alcoholism, promiscuity, suicide and murder. Right at the end, however, a newly introduced character delivers a scathing diatribe riddled with revolutionary rhetoric about how the one truly powerful love, i.e., that between women, will topple capitalism and patriarchy alike. Whenever I have shown this book to friends in the past few years, reactions ranged from amusement to incredulity to the odd shriek of delight at this example of lesbian retro chic. Clearly, the book and its contents have gone from being outrageous to being all the rage.

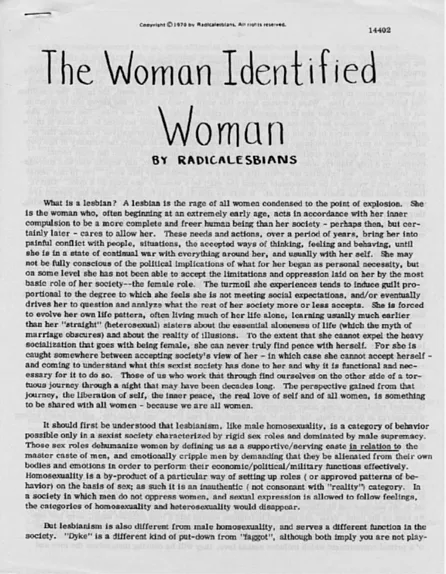

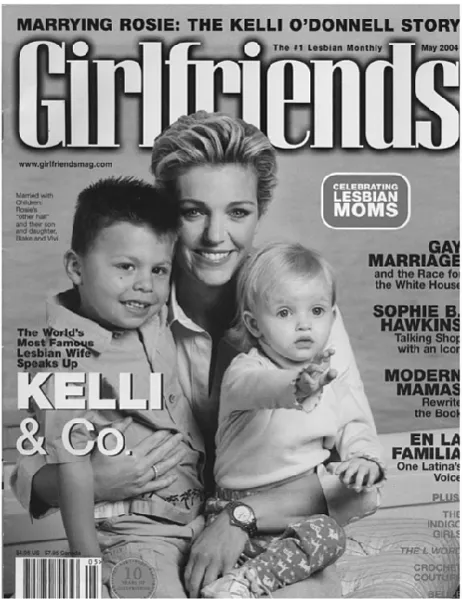

This study traces that shift, looking at what images of a lesbian community self-identified lesbian authors in the US and Britain have communicated in non-fictional texts since 1970, how this change can be traced in texts such as pamphlets, magazine articles and blogs, and, finally, why this change has taken place. To put it in a nutshell, how and why did lesbian discourses, and the images of community that they transport, change from what we can see reflected in Figure 1.1 to what is conveyed by Figure 1.2? A close linguistic analysis of texts not only shows how change was effected, but also how particular historical narratives were constructed that do not necessarily reflect the complex reality of the times they refer to.

As the title of this book indicates, community is here understood as an ‘imagined community’ (Anderson 1983), i.e., as a model of a collective identity that shapes but ultimately supersedes local communities. The social constructionist view, according to which the ‘subject is produced … across a multiplicity of discourses’ (Fuss 1989, p. 97), holds true for

the lesbian community as a collective actor as well. Images of such communities are largely, if not exclusively, an effect of discourse, i.e., accumulations of texts that particular people produce, distribute and receive in a particular way and as a form of social action. As such, any identity of discourse participants, including their collective identity as members of a community, is always preliminary, negotiable and open to change. For the

researcher who wants to find out about what images are constructed in discourse, and how this is achieved, it is logical then to turn to texts as the main source of data.

However, just as ‘the search for an authentic women’s speech overlooks the instability of gender divisions and the many differences between women’ (McIlvenny 2002b, p. 5), research into lesbian discourse will not reveal any typically lesbian way of using language. Rather, such research will uncover the discursive and cognitive repertoires drawn upon by self-identified lesbian writers at various points in history to construct and negotiate an image of lesbian community. Further, the study primarily addresses the image of lesbian community in discourses that involve self-identified lesbians, rather than the image of lesbians in mainstream discourse. This is despite the fact that lesbian notions of collective identity, and the discourses that effect and transport them, are not generated in a void, but influenced by the host culture in which they are embedded. Such influence may take the form of lesbians uncritically adopting society’s view of them, as can be seen for many texts of the 1950s. Alternatively, lesbians may use texts to destabilize dominant views and establish a counter-model, as is the case in many instances of lesbian discourse from the 1970s. For various socio-economic reasons, lesbian and mainstream discourses have become more closely and explicitly linked since 1990 (see Chapters 5 and 6), with lesbian authors integrating features of mainstream discourses, and the images propagated in them, for the construction of their own models of community.

Although the attitudes with regard to both women and homosexuality have changed remarkably in both the US and the UK over the past three decades, this is not to say that lesbians as a social group, or indeed as individuals, have achieved full equality and freedom from discrimination. Sexual harassment and violence directed specifically against lesbians, discriminatory legislation, or just plain heteronormativity are still strong in both cultures, attempting to silence lesbians and make them invisible. As a marginalized social group, lesbians and their discourses are prime candidates for the academic field of critical discourse analysis (CDA), the aim of which it is to unveil, through linguistic analysis, the ideological underpinnings of discourses that lead to social injustice, and thereby lay the ground for political intervention. Yet, while a huge amount of literature can be found concerning questions of gender and ethnicity, comparatively little has been written on the subject of sexual identity from a CDA perspective (e.g., Higgins 1995; Morrish 1997; Livia 2002a; Baker 2005). While this study does not seek to unravel how ‘heterosexual … power elites’ (van Dijk 1993, p. 254) use textually mediated social action to marginalize lesbians by constructing a particular image of them, CDA, especially in its discourse-historical (Wodak 2001) and socio-cognitive varieties (Chilton 2005; van Dijk 2006a), still seems like a promising approach to the study of (written) texts by lesbian authors. CDA can contribute to this study in these ways:

• to establish how social change is reflected in, and produced by, texts,

• to link texts to textually mediated interaction, i.e., production, distribution and reception, as well as to wider socio-historical contexts, and

• to look at the (self-)representation of social groups and how it effects or challenges marginalization and power asymmetry within and between groups.

As such, the analytical model proposed in this book should prove useful for the diachronic study of the discursive construction and cognitive structure of collective identity in general.

CDA is interested in revealing the ideological underpinnings of discourse, including the discourse of the researcher herself. Accordingly, there can be no neutral academic account of the texts and discourses under investigation. Instead, ‘critical discourse analysts … take an explicit sociopolitical stance: they spell out their point of view, perspective, principles and aims’ (van Dijk 1993, p. 252). Rejecting objectivity means realizing that ‘communities are imagined on a number of levels, including the ways in which researchers themselves imagine the communities which they study’ (Queen 1997, p. 237). An example of this is the study by Day and Morse (1981), who investigate conversations among long-term lesbian couples and find that ‘lesbian communication patterns are characterized by … symmetry’ (p. 86), which in the authors’ interpretation reflects the egalitarian nature of lesbian relationships as an alternative to heterosexual marriage. This interpretation reflects widely held views on lesbian relationships at the time and is therefore rather predictable. In the following analyses, I have tried to be as fair and represent as wide a range of views on lesbian collective identity as possible. However, a completely impartial stance seems impossible for any participant-observer, who is bound to be influenced by her own experiences with and in the community under investigation.

I have been a part of local lesbian communities since the early 1990s, be it as a member of grassroots political groups or lesbian and gay event organizations, as one node in a friendship network or as a researcher. Engaging with lesbians has been of varying importance to me over the years, in line with shifts in my own social, professional and sexual identity. In the ten years that I have intermittently been working on this book, my attitudes, values and beliefs have differentiated, partly as a result of engaging with a wide variety of lesbian texts and contexts. Consequently, my own politics have become increasingly eclectic, and I can now subscribe to at least some aspects of all the different views and images discussed in this book.

Any historical study runs the risk of imposing a false coherence on the past. For example, the early texts analyzed in Chapter 3 became iconic only retrospectively, through a historical narrative. One aim of the study is to show how this retrospective narrative informed later texts in their construction of community. Given the aforementioned impossibility of a neutral stance, however, the project to some extent continues a retrospective narrative. After all,

There are many stories which this book does not tell. The first concerns the focus on Anglo-American culture. It has been pointed out that ‘the term “lesbian” is of European origin, yet woman-to-woman desire and love has origins, expressions, and terminologies that are grounded in various geographies and cultures’ (Seif 1999, p. 34). It is therefore important to flag up the Anglo-American specificity of ‘lesbian’ as an identity label, to acknowledge traditions of desire between women in other cultures, and to address sexual identities as they are carved out through language in a globalized world, as scholars increasingly do (Leap & Boellstorff 2004; Sauntson & Kyratzis 2006b). If this book fails to do justice to lesbian life outside the Anglo-American world, it does so for reasons having to do with its development. The study originally started out as my MA dissertation, which I submitted at the English Department at Vienna University and which therefore required data from an English-speaking country. Britain proved the most practical and least costly choice for data collection, especially since I knew of several feminist and lesbian libraries and archives there. In the more advanced stages of the project, it became clear that despite cultural differences, lesbian discourses in the UK cannot be understood without recourse to some of their models in North American discourses, and the focus was therefore extended to include the US as well. Also, when I decided much later to publish a study on lesbian discourses with Routledge, one condition was that the book should also incorporate the US context, in order to tap that market. I eventually chose this publisher, rather than an independent one, because for political reasons, I wanted a book with ‘lesbian’ in the title to have maximum impact. Paradoxically, global distribution and—hopefully—reception only comes at the price of a narrowing in perspective.

The second gap is temporal rather than spatial. The present study starts with the Stonewall Riots as a more or less arbitrary cut-off point: on 28 June 1969, the police raided the gay bar Stonewall on New York City’s Christopher Street. The ensuing street fighting continued for days and marks—under the name of Stonewall Riots—the beginning of the lesbian and gay movement. The annual Pride marches held in many cities around the world celebrate this event (Faderman 1991, pp. 194–5). Although the turn of the decade can be regarded as a watershed in lesbian history, it is of course true, as Stein (1997, p. 27) remarks, that ‘lesbian life … did not begin in 1970.’ It is further important to ask in how far a division into decades does justice to the development of lesbian discourses and their notions of community. Such a partitioning is of course to some extent arbitrary and was mainly adopted to provide an overall structure to the book. The goal of the discourse-historical approach that informs the project is to show the continuous development of images of community in lesbian discourses and to account for the reasons and processes of this change. The development is understood to be less than clear-cut, and is made even more complex by the only partial overlap between UK and US communities and discourses. Indeed, there are intertextual links between asynchronous texts, usually in that US texts impact on those produced in the UK. Whenever appropriate, these interrelations will be discussed and reference will be made not only to lesbian communities outside the US and the UK, but also to earlier lesbian discourses and their images of community. The same goes for other omissions, such as bisexual and transgender identities, and the interrelations betwe...