1 Migration and poverty alleviation in China

Dewen Wang and Fang Cai

Introduction

This essay examines the place of migration within China’s ongoing poverty alleviation efforts. The discussion shows that rural–urban labour migration has played a pivotal role in poverty alleviation in rural areas, a role that has been enhanced through explicit government initiatives to link migration with the expansion of employment opportunities for rural people and to use education, training and credit assistance to enable individuals in very poor households to migrate. At the same time, the discussion shows that rural–urban labour migration presents new challenges for government approaches to poverty alleviation in cities where migrants face particular vulnerabilities on account of institutional and social exclusion. To provide context for delineating and evaluating the impacts of migration on poverty alleviation in China it is useful to begin with a brief overview of key poverty trends.

Since the launch of the reforms in the late 1970s rapid economic growth, together with a well-funded national poverty reduction programme, dramatically reduced the incidence of poverty in China’s countryside. Official estimates indicate that between 1978 and 2005 the rural population living in poverty decreased from roughly 250 million to 23.7 million and poverty incidence fell from 30.7 per cent to 2.6 per cent over that same period (see Table 1.1).

The progress of rural poverty alleviation can be divided into four phases (see Table 1.1). The first phase was from 1978 to 1985. During this stage, the rural population living below the official poverty line fell from 30.7 per cent to 14.8 per cent (see Table 1.1). This 50 per cent reduction can be largely attributed to the success of the rural household responsibility system and the decollectivisation of agriculture with the attendant increase in agricultural productivity. The second phase of rural poverty alleviation started in 1986, but stagnated in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Although the Chinese government intentionally initiated large-scale regional development programmes to further reduce the numbers of remaining rural poor, the cooling down of economic growth stymied the pace of poverty reduction, and there were setbacks in 1989 and 1991 respectively. In 1993, the announcement of the ‘8-7’ Poverty Reduction Plan marked the beginning of the third phase. This plan called for national strategic action to reduce the numbers of rural poor by 80 million during the period 1994 to 2000. In implementing this programme, the government budgeted special poverty alleviation funds (PAFs) consisting of fiscal alleviation funds, food for work funds, and interest-subsidised loans to support economic growth in designated poor areas. With the accomplishment of this plan, the number of the rural poor dropped to 32 million with a poverty incidence of 3.4 per cent (China’s News Office of the State Council, 2001).

Table 1.1 Rural poverty alleviation: 1978–2004

Since the start of the new millennium, poverty alleviation in rural China has entered a new stage. The policy emphasis has been increasingly aimed at village-based and/or rural household-based development programmes rather than at previous county-based schemes. The new method endeavours to reach the remaining rural poor directly and to lift them out of poverty through improved targeting and financial utilisation.

Notwithstanding the remarkable progress already made, China is now facing a number of new difficulties in reducing poverty. First, the deceleration of poverty reduction in the countryside contrasts with the increasing marginal cost, which suggests greater difficulties in lifting the remaining rural poor out of poverty. The average annual change in poverty incidence dropped from 1.5 per cent in 1980s to 0.7 per cent by 1990s, falling further to 0.1 per cent since 2001. Meanwhile the annual Poverty Alleviation Fund input in 2001 and 2002 was 3.7 times higher than during the first half of 1990s, and double that of the second half of 1990s (see Table 1.1). Second, the nature of rural poverty have changed. The majority of the remaining rural poor are increasingly concentrated in remote and mountainous townships and villages in the western provinces; these people endure low educational attainment, poor health, bad living and reproductive conditions, and marginalisation (Asian Development Bank 2004; Cai and Du 2005). Their extreme and chronic poverty requires more specific poverty reduction measures.

Third, new issues of urban and migrant poverty have emerged. Prior to the 1990s, the poverty issue in urban China was of less significance than at present because the numbers of urban poor were far fewer, and the social and economic development needs of people were well provided for under the urban social relief system. For instance, in 1990 the number of the urban poor stood at 1.3 million with a poverty incidence of 0.4 per cent (World Bank 1992). Since the 1990s, the process of labour and social security reform in both state-owned enterprises and the urban private sector caused millions of workers to become redundant and tens of thousands of urban families to fall into poverty. Khan (1998) found that the urban poverty incidence increased by 12 per cent from 1988 to 1995. Updated statistics show that in 1999 the number of urban poor had reached 23 million with a poverty incidence of 5.1 per cent, with the poverty being more severe than in 1995 (Li 2001). If migrants are included, the issue of urban poverty becomes even more serious. Li (2001) reported that the poverty incidence of migrants is double that of urban residents with a local urban residence permit (hukou). According to a study of 31 large cities, the poverty incidence of migrants was over 50 per cent higher than for urban residents who had a local urban hukou and, in some cities, it was two to three times higher than for local residents (Hussain 2003). Therefore, attention to emerging urban poverty and to migrant poverty in particular, is an important component of China’s future strategies for promoting the poverty alleviation, livelihood security and social harmony dimensions of social development.

Finally, income disparities between rural and urban areas and among regions have been worsening along with rapid economic growth. Rural–urban income inequality narrowed during the earlier years of reform, but has increased since the mid-1980s. From 1978 to 1985, the ratio of urban to rural per capita net income dropped from 2.57:1 to 1.53:1, but then rose to 2.42:1 in 2004 (see Table 1.2). If we take into account the subsidised public services and welfare benefits in urban areas, the current rural–urban disparity in China would be the largest in the world (Li and Yue 2004). Ravallian and Chen (2004) documented that the overall rural and rural–urban income inequalities have been increasing since the beginning of 1980s. Labour market distortions are among the most important factors responsible for this increase, with significant direct and indirect effects on labour mobility and rural income.

Table 1.2 Income inequalities in China: 1978–2004

The remainder of this chapter explores the relationship between migration and poverty alleviation. The first part examines the relationship between economic growth, employment and poverty alleviation; the second part describes the institutional conditions of migration, and the ways in which migration trends are shaped by trends in income inequality; the third part depicts the characteristics of poor households and analyses the contribution of migration to poverty reduction in sending places; the fourth part examines the urbanisation of poverty, and the final part concludes with policy suggestions.

Employment nexus between economic growth and poverty alleviation

Economic growth and poverty alleviation

Whether or not economic growth is pro-poor depends on its speed and quality. Since the start of the economic reforms, China’s economy grew at an annual rate of about 10 per cent, with some cyclical characteristics over time. This rapid economic growth ensured China’s large reduction of rural poverty, especially during the earlier reform period.

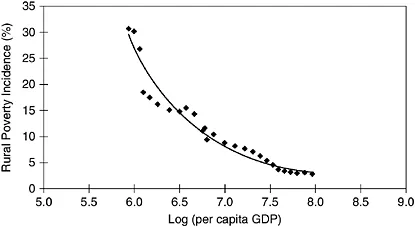

Plotting the poverty incidence against income growth reveals the importance of economic growth in the process of poverty reduction. Figure 1.1 demonstrates that the rural poverty incidence has declined along with the growth of per capita gross domestic product (GDP). Results from a simple regression model using rates of provincial rural poverty reduction from 1991 to 1996 on GDP growth reinforce the conclusion that provinces with more rapid per capita GDP growth also show a more rapid decline in the numbers of rural poor (World Bank 2001). The coastal provinces took the lead in initiating economic reforms and achieved faster economic growth, leading also to much faster rural poverty reduction compared to central and western regions.

Huang et al. (2005) regressed the national (and provincial) rates of rural poverty against per capita GDP and confirmed that economic growth significantly affects poverty reduction, though the growth elasticity of poverty declines with the increase in per capita GDP. They pointed out that if the inter-country data from the 2003 Global Development Report were used in the regression, a U-shaped relationship can be found between income level and poverty incidence with a turning point at US$ 25,000. Because all developing countries are below that level, faster economic growth will have a stronger impact on poverty reduction during the initial stages of economic growth, but with a diminishing effect as an economy becomes wealthy and mature.

Figure 1.1 Economic growth and rural poverty alleviation.

Source: National Bureau of Statistics (2005), China Yearbook of Rural Household Survey (2005).

The above empirical evidence is consistent with findings from other sources (Chen and Wang 2001; Jalan and Ravallion 1998; Khan 2000), which testify that economic growth is an important factor in China’s poverty reduction efforts, but that its effects have been declining since the mid-1980s. Slow agricultural growth is one factor that weakens the effects of economic growth on poverty reduction.

Between 1978 and 1984 agricultural growth in China was impressive. The value of agricultural output grew at an annual rate of 6.9 per cent, up from 2.5 per cent in the period 1952–1978. The annual growth rates for grain, cotton and oil seeds were 4.8, 17.7 and 13.8 per cent, respectively (National Bureau Statistics 2005). As a result, rural per capita income almost tripled and the number of rural poor was halved during that period.

Compared with the fast growth during the initial reform stage, agricultural growth slowed down to between 3.1 and 4.6 per cent between the late 1980s and the beginning of this century. In the meantime, the share of agricultural output in GDP decreased from 31.4 per cent to 15.2 per cent (see Table 1.3). Slow agricultural growth not only allows non-agricultural sectors to become the major contributors of economic growth, but also delays lifting the rural poor out of poverty because they rely mainly on agriculture for their household income and cannot equally enjoy the gains from the rapid growth of non-agricultural sectors. Chen and Wang (2001) used household survey data from 1990 to 1999 to empirically show that the poor have gained far less from economic growth than the rich, and that only 20 per cent of the richest had income growth equivalent to, or greater than, GDP growth. As a result, rising income inequality disconnects poverty alleviation from economic growth.

The increasing rate of accumulation and investment, which caused the difference between economic growth and income growth, is also one of the determinants of the slowdown in poverty reduction (Khan 2000). The arithmetic average growth rates of per capita GDP, rural and urban per capita income from 1978 to 1984 are 8.2, 15.9 and 6.6 per cent, respectively; the growth of per capita GDP does not change from 1985 to 2002, while the growth rates of rural and urban per capita income drop to 4.3 per cent and 6.3 per cent, respectively. The growing gap between economic growth and income growth accounts significantly for a decrease in the speed of poverty reduction and an increase in the numbers of the urban poor (Lin and Li 2005). In fact, the high-speed economic growth propelled by investment comes to some degree at the expense of the slow growth of employment because it dilutes the ‘trickle-down’ effect.

Table 1.3 Economic growth in China: 1978–2004

Non-agricultural employment and poverty alleviation

Employment is the major activity for generating family income. The growth of rural income can be divided into agricultural and non-agricultural revenues. With slow agricultural growth, non-agricultural revenue becomes the main source of household income growth through non-agricultural employment. The share of wage income in rural household income increased from 17 per cent in 1985 to 34 per cent in 2004. In urban household income, wage income accounts for more than 70 per cent (National Bureau of Statistics 2005). If a family member is underemployed, the whole family income will be dramatically reduced. Therefore, wage-earning employment will be the crucial channel for maintaining family income and benefits from rapid economic growth.

Like fast agricultural growth, the rapid development of Township and Village Enterprises (hereafter referred to as TVEs) has also had a very positive impact on poverty reduction through the creation of non-agricultural employment. In 1978, total industrial production of TVEs was 49.3 billion yuan, accounting for 11.6 per cent of GDP. In 1992, this figure rose to 2,036 billion yuan, accounting for 38.6 per cent of gross national industrial product. From 1978 to 2003 the real growth rate of gross output was 28.0 per cent per year, creating millions of non-agricultural employment opportunities that facilitated the transfer of surplus rural labour. From 1978 to 2003 the number of people employed in TVEs rose from 28.3 million, accounting for 9.2 per cent of rural employment, to 138.7 million or 28.5 per cent of rural employment, with an average annual growth rate of 6.1 per cent (Ministry of Agriculture 2004).

The development of rural industrialisation has not been uniform across regions. In the early 1980s, the number of non-agricultural workers actually decreased in the poor central and western regions as the commune system was dismantled. In 2004, 53.4 per cent of TVE employment was concentrated in the eastern regions, compared to 27.7 per cent in the central and 19.0 per cent in the western regions (Ministry of Agriculture 2004). Regional differences in rural industrialisation caused regional differences in non-agricultural employment, thereby affecting the speed of rural poverty reduction. Since the rural poor are increasingly concentrated in remote and mountainous areas, slow agricultural growth and less developed industrialisation has limited poverty reduction in those areas.

The decline in the elasticity of employment that equals employment growth caused by corresponding GDP (or output) growth, further illustrates the decreasing effects of economic growth on employment and poverty reduction. As shown in Figure 1.2, the employment elasticity in non-agricultural sectors (including industry and tertiary industry) has a downward trend. In 1980s, China’s annual average GDP growth was 9.8 per cent, and employment elasticity 0.56 per cent. In the 1990s, China’s GDP grew at an annual rate of 9.3 per cent, while the elasticity of employment was 0.33 (National Bureau of Statistics 2005). TVE employment growth was strongest in the late 1980s and early 1990s, but its employment elasticity has also declined since then. The distortion of factors of production and economic restructuring towards capitalisation are the main reasons for the declining employment elasticity in non-agricultural sectors, which not only limits the full utilisation of China’s abundant labour resources, but also hinders rural labourers from taking advantage of the opportunities of rapid economic growth to improve their quality of life.

Institutional reform and migration

Trends in rural to urban migration

In a country with such a huge population and so little land, rural labourers have strong incentiv...