1 Australia, New Zealand and Maritime Security

Natalie Klein, Joanna Mossop and Donald R. Rothwell

Any consideration of the maritime security dimension of a single state raises multiple issues. A consideration of the maritime security dimensions of two states expands that consideration considerably. In the case of Australia and New Zealand there are, however, connecting threads which make that consideration not only possible but also sensible. Evans and Grant argued in 1995 that ‘Australia and New Zealand are as close as two countries that almost became one could be’,1 and whilst there have been some emerging distinctions between the two countries over the past decade, principally as a result of Australia’s growing multiculturalism, the historic and contemporary political, economic and social ties remain as strong as they have ever been.2 Australia and New Zealand have a long history of close economic integration, and in early 2009 these mutually shared interests were once again highlighted by the conclusion of the ASEAN–Australia–New Zealand Free Trade Agreement (AANZFTA),3 reflecting the joint trading interests of both countries with South East Asia.4

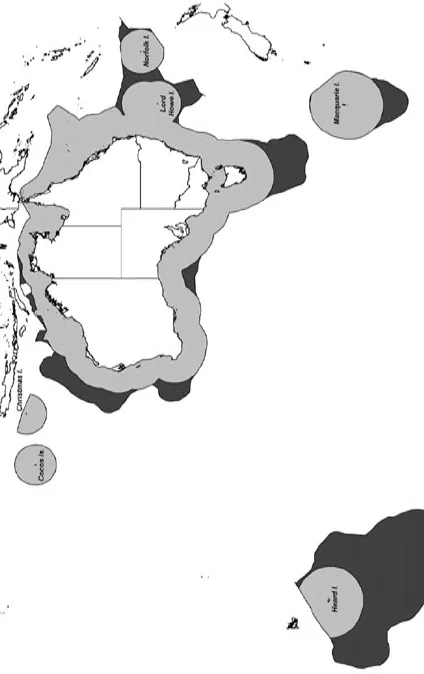

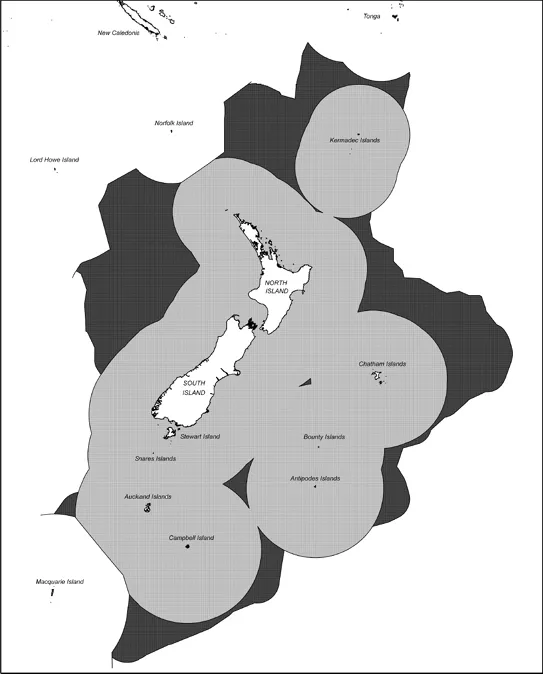

In the South West Pacific, Australia and New Zealand are the two largest states in land size, population, economies, and their maritime domain. As countries with economies that have traditionally relied upon extensive overseas trade of natural resources and agriculture, the maintenance of shipping routes not only within the immediate region but also beyond has been essential to the economic stability of both countries. When this factor is combined with the extensive coastlines possessed by both countries, and their capacity in the last half-century to assert increasingly extensive maritime claims, it is not surprising that Australia and New Zealand have such strong interests in maritime security. The extent of Australia and New Zealand’s maritime zones are depicted, respectively, in Figures 1.1 and 1.2.

The two countries have a long history of cooperating in military contexts. Having been active participants in World Wars I and II, which in the case of the 1915 Gallipoli campaign became the basis for the shared ANZAC military tradition in both countries,5 Australia and New Zealand actively sought out post-war regional security alliances and arrangements to their mutual benefit.6 The 1951 ANZUS Treaty7 between Australia, New Zealand and the United States (US) remains the most self-evident expression of the mutual security cooperation framework which both countries sought to develop at that time. The ANZUS framework for defence and security cooperation continues, albeit with the New Zealand–US relationship suspended due to New Zealand’s policy of prohibiting nuclear ship visits.8 There have been other expressions of this shared engagement in regional security frameworks including the 1954 SEATO Treaty,9 and the Five Power Defence Arrangements individually and mutually entered into with Malaysia and Singapore.10 In more recent times, Australia and New Zealand have undertaken shared military operations throughout the region, including in 1999 with the Australian-led INTERFET intervention into East Timor,11 and in 2003 with the RAMSI stabilization mission in the Solomon Islands.12

Figure 1.1 Australia’s Maritime Zones.

Figure 1.2 New Zealand’s Maritime Zones.

The relationship between the two countries in relation to military issues has not been without its problems. The ANZUS dispute and changes to the way New Zealand subsequently focused its defence policy on multilateral engagement has caused tension at times, with disagreements about the role that New Zealand can play in supporting Australia’s armed forces.13 However, despite this debate that persists at a high level, the cooperation that has resulted from the various joint and multilateral South Pacific and East Timorese operations mentioned above, as well as a project in the late 1980s and 1990s to develop a joint ANZAC frigate construction programme, has helped to maintain the relationship.14

Australia and New Zealand on the basis therefore of their long-standing relationship and mutual interests in South East Asia and the South West Pacific also have shared interests with respect to maritime security. The purpose of this chapter is to explore what is maritime security, how it may be defined and articulated in both countries, and to consider some of the particular maritime security dimensions that exist for Australia and New Zealand individually and collectively.

1 What is ‘maritime security’?

The term ‘maritime security’ has different meanings depending on who is using the term or in what context it is being used. From a military perspective, maritime security has traditionally been focused on national security concerns in terms of protecting the territorial integrity of any particular state from armed attack or other uses of force and projecting the state’s interests elsewhere. Defence perspectives on maritime security have subsequently broadened to encompass a greater range of threats. For example, the US Naval Operations Concept refers to the goals of ‘maritime security operations’ as including ensuring the freedom of navigation, the flow of commerce and the protection of ocean resources, as well as securing ‘the maritime domain from nation-state threats, terrorism, drug trafficking and other forms of transnational crime, piracy, environmental destruction and illegal seaborne immigration’.15

For operators in the shipping industry, maritime security is particularly focused on the maritime transport system and relates to the safe arrival of cargo at its destination without interference or being subjected to criminal activity.16 Consistent with this perspective, Hawkes has sought to define maritime security as ‘those measures employed by owners, operators, and administrators of vessels, port facilities, offshore installations, and other marine organizations or establishments to protect against seizure, sabotage, piracy, pilferage, annoyance, or surprise’.17

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has addressed questions of maritime security under the auspices of its Maritime Safety Committee since the 1980s.18 In this context, a distinction is drawn between maritime safety and maritime security. Maritime safety refers to preventing or minimizing the occurrence of accidents at sea that may be caused by sub-standard ships, unqualified crew or operator error, whereas maritime security is related to protection against unlawful, and deliberate, acts.19

International lawyers referring to questions of maritime security may seek to have regard to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (LOSC),20 occasionally described as the ‘constitution of the oceans’, as a point of reference for defining or at least understanding a term related to the law of the sea. Despite the states parties to the LOSC desiring to settle ‘all issues relating to the law of the sea’, there are scant references to security in the convention,21 and certainly no clear-cut definition of what maritime security might mean within the law of the sea. At most, some indication of what is meant by security may be drawn from the LOSC in its treatment of the right of innocent passage and the identification of a series of activities that would be inconsistent with that right and hence prejudicial to the peace, good order and security of the coastal state.22 From this perspective, it is not only a range of military activities that may pose a threat to the security of the coastal state (such as weapons exercises, the threat or use of force, or the launching, landing or taking on board of any aircraft or military devices), but also includes fishing activities, wilful and serious pollution and research or survey activities.23

International relations scholars have long studied questions of security, and it is generally acknowledged that in the post-Cold War and globalization era security concerns are no longer focused on military interests, in terms of a state being able to avoid war or otherwise prevail in any war. Threats to a state’s security may not only be military but also political, economic, societal and ecological.24 From a maritime perspective, the oceans have been viewed as ‘particularly conducive to these types of threat contingencies because of [their] vast and largely unregulated nature’.25 As a result, discussions about maritime security have similarly broadened for international relations scholars, with greater focus on acts of terrorism, transnational crime and environmental harm as influential on traditional concepts of ‘sea power’.

The United Nations Secretary-General has acknowledged that there is no agreed definition of ‘maritime security’, and has instead identified what activities are commonly perceived as threats to maritime security.26 In his 2008 ‘Report on Oceans and the Law of the Sea’ the Secretary-General identified seven specific threats to maritime security. First, piracy and armed robbery against ships, which particularly endanger the welfare of seafarers and the security of navigation and commerce.27 Second, terrorist acts involving shipping, offshore installations and other maritime interests, in view of the widespread effects, including significant economic impact, that may result from such an attack.28 Third, illicit trafficking in arms and weapons of mass destruction.29 Fourth, illicit trafficking in narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances, which takes into account that ‘approximately 70 per cent of the total quantity of drugs seized is confiscated either during or after transportation by sea’.30 Fifth, smuggling and trafficking of persons by sea, posing risks due to the common use of unseaworthy vessels, the inhumane conditions on board, the possibility of abandonment at sea by the smugglers, and the difficulties caused to those undertaking rescues at sea.31 Sixth, illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing in light of the identification of food security as a major threat to international peace and security.32 Finally, intentional and unlawful damage to the marine environment as a particularly grave form of maritime pollution due to the potential to threaten the security of one or more states given the impact on social and economic interests of coastal states.33 This listing encompasses the varied concerns of shipping operators, government defence forces and other maritime security analysts.

Even when a precise definition of ‘maritime security’ is eschewed, identifying what is a threat to maritime security has not been free from controversy. At the 2008 meeting of the UN Open-ended Informal Consultative Process on Oceans and the Law of the Sea (UNICPOLOS), state representatives contested the inclusion of IUU fishing as a threat to maritime security.34 Instead, it was proposed that the General Assembly recognize ‘that illegal fishing poses a threat to the economic, social and environmental pillars of sustainable development’ and that ‘some countries’ had found i...