![]()

Part I

Introduction

![]()

1

Transforming the built environment through construction innovation

Peter Newton, Keith Hampson and Robin Drogemuller

Achieving sustainable urban development for a projected global population of 9.2 billion in 2050, 70 per cent of whom will be living in urban settings (United Nations 2008), represents one of the principal challenges of the twenty-first century. Australia, as one of the world’s most urbanized societies, led this global transition 125 years ago. Its cities are classed among the world’s most liveable. Liveability, however, does not equate to sustainability. Indeed the current trajectory of Australia’s urban development has been classed as unsustainable (Newton 2006, 2007a).

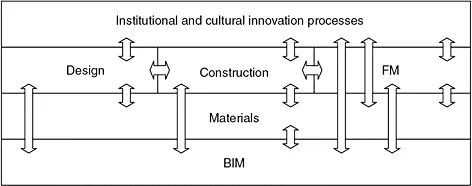

Transforming buildings and infrastructure to become more sustainable elements of our built environment is a key challenge for the property, construction, planning, design and facilities management industry, as well as governments at all levels. The roadmap by which this built environment transformation can be driven is clear but complex (see Figure 1.1).

At the heart of the transition is the promise of virtual building – an ability to assess the performance of a proposed built asset (e.g., lifetime cost, environmental impact, social benefit, locality impact) prior to construction. Central to virtual building is the building information model (BIM), an integrative digital technology that permits information-sharing between disciplines. Together with the work of the OGC (Open Geospatial Consortium), BIM provides the basis for a more rigorous cross-disciplinary specification of information required for a convergence of building science, design science, engineering and construction, environmental science, management science and spatial science knowledge in a modelled representation of a complex system, which is the built environment. The city of bits is a powerful metaphor first introduced by Bill Mitchell (1995) that has stimulated our thinking about the manner in which a complex city can be conceived – as a collection of material objects with different attributes and behaviours that can be assembled and re-assembled in a myriad of ways to deliver our living and working built environment.

Developments in materials and manufacturing processes, and in design, construction and facilities management processes, are all providing the basis for a transformation in the built environment sector that will be required to meet the challenges of:

• a rapidly growing population;

• increasing consumption;

• a resource-constrained world;

• a carbon-constrained world linked to greenhouse gas emissions and climate change;

• increasing urbanization in advanced industrial, newly industrializing and less developed countries – each with similar built environment goals, but different endowments in natural, human and financial capital;

• globalization and the competitiveness that is unleashed for industry efficiency.

An awareness that the built environment design, construction and facilities management industry was lacking in the levels of productivity, competitiveness and innovation apparent in other industrial sectors has led to a series of initiatives by the Australian government and industry seeking to identify how technology, product and process innovation in the IT, materials, design, construction and facilities management domains can be more successfully identified, diffused and implemented within an architecture, engineering, construction and operations (AECO) organization (again, see Figure 1.1).

To become more sustainable, the built environment will need to embody significantly higher levels of innovation – in its products and processes – than was characteristic of the previous century. The Cooperative Research Centre for Construction Innovation (CRC CI) was established in 2001 with a charter to assist the AECO industry deliver a more competitive and environmentally sustainable built environment. Ecoefficiency innovation was a key objective of applied R&D undertaken within the Sustainable Built Assets program of the CRC in close collaboration with its IT Platform – one of the key convergences it pioneered between design science and sustainability science.

The sections that follow focus on the significance, key challenges and principal transitions required in:

• the built environment;

• the AECO industry;

• innovation systems, including contributions made by the CRC CI to assist in the transition to a more sustainable built environment.

The built environment

Significance

The importance of the built environment is unquestionable. It is typically a nation’s greatest asset (Newton 2006). It is where a nation’s population lives and, in advanced industrial societies, where 95 per cent of the population works and where approximately 80 per cent of national GDP is generated: ‘Its design, planning, construction and operation is fundamental to the productivity and competitiveness of the economy, the quality of life of all citizens, and the ecological sustainability of the continent’ (Newton et al. 2001). The built environment also represents the myriad of enclosed spaces – homes, offices, shopping centres, entertainment venues, transport vehicles – where the population, on average, spends 97 per cent of its time (Newton et al. 1997).

Preference for urban (as opposed to rural) living is strong in Australia, where approximately 88 per cent of the population lives in centres of 1,000 or more residents (Newton 2008a). This is now a dominant global trend – and accelerating. The planning and management of sustainable urban settlement is possibly the greatest global challenge of the twenty-first century, especially when it is coupled with adaptation to the projected impacts of climate change and resource constraints.

Key challenges

The challenges faced by Australian built environments are well established (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Environment and Heritage 2005, 2007; Newton 2006, 2008b), and are summarized below.

Efficiency and competitiveness

In a globalized world, a nation’s built environments are often assessed in terms of their contribution to international competitiveness (OECD 2008). Engineers Australia’s Infrastructure Report Card (Hardwicke 2008) has assigned an overall rating of C+ (within an A–F range) for Australia’s roads, rail, electricity, gas, ports, water and airports, in large part due to a significant backlog in infrastructure expenditure (Regan 2008). Costs of urban traffic congestion have been forecast to increase from approximately A$9.4 billion in 2005 to an estimated A$20.4 billion by 2020 (BTRE 2007). Infrastructure performance will be further tested by projected impacts of climate change (CSIRO et al. 2007).

Resilience to climate change

In relation to forecast impacts of climate change (Hennessy 2008), Australia stands to suffer more than any other developed country. Resilience will be tested in terms of built environment adaptability to:

• sea-level rises in combination with storm surges and their impact...