- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

English and Celtic in Contact

About this book

This book provides the first comprehensive account of the history and extent of Celtic influences in English. Drawing on both original research and existing work, it covers both the earliest medieval contacts and their linguistic effects and the reflexes of later, early modern and modern contacts, especially various regional varieties of English.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access English and Celtic in Contact by Markku Filppula,Juhani Klemola,Heli Paulasto in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Early Celtic Influences in English

1 The Historical Background to the Early Contacts

1.1 THE ARRIVAL OF THE ANGLO-SAXONS AND THE CONQUEST OF BRITAIN

The mid-fifth century AD has come to be cited as the crucial date which marks the beginning of a new era in the relationship between the Insular Celts and the Anglo-Saxons. The last Roman legions had left Britain in the early part of the fifth century, leaving behind a country which was characterised by confusion and lack of a strong administrative centre. Although there is evidence for some amount of contacts between the Celts (i.e. Britons) and the Anglo-Saxons even before the mid-fifth century (see, e.g. Jackson 1953: 197; Higham 1994: 118–145), historical tradition has it that it was in 449 that the first major Anglo-Saxon force, led by Hengest and Horsa, set foot in Britain. Though first invited by the Britons as allies against foreign raiders such as the ‘Picts’ of Scotland and the ‘Scots’ (i.e. the Irish), they soon embarked on a series of rebellions against their hosts, which eventually led to an almost wholesale conquest of Britain within the next couple of centuries. As Jackson (1953: 199) writes, our main source of information here is the historical account by the British monk Gildas, who according to Jackson wrote his De excidio et conquestu Britanniae sometime in the first half of the sixth century. Sims-Williams (1983: 3–5) points out some caveats in this dating, including the doubtful authority of the Annales Cambriae, on which it mainly rests. He is himself content to settle for a fairly broad dating in the sixth century, at a period earlier than the first reference to Gildas by Columbanus ca 600, and later than the fifth century “because of Gildas’s vagueness about the known history of the early part of that century” (op. cit., 5). However, a somewhat earlier date is proposed by Higham (1994: 141), who places the composition of De excidio within the late fifth century, that is, around fifty years after the adventus Saxonum. Although little is known about Gildas’s person or even where he wrote his work, there is evidence which suggests that he was based somewhere in central southern England (Higham 1994: 111–113; see, however, Sims-Williams 1983 for a more sceptical view). Other important near-contemporary sources are the two Gallic Chronicles of 452 and 511 (see Higham 1992: 69). Well-known, though significantly later, sources are the Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum from the early eighth century, written by the Anglo-Saxon monk Beda Venerabilis (the Venerable Bede), and somewhat later still, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which was compiled by several authors working in different places at different times, with the earliest versions dating from the ninth century.

While the first hostilities between the Britons and the Anglo-Saxons were relatively widespread and extended even to the western parts of Britain, they did not lead to permanent settlements by the latter except in some eastern parts of the country. Furthermore, after their initial setbacks, the Britons were able to fight back the invading Anglo-Saxon armies and even secure peace for some decades during the latter half of the fifth century. Gildas names Ambrosius Aurelianus, a British aristocrat probably of Roman extraction, as the person who was alone able to rally the Britons behind him to battle off the Saxon armies:

After a time, when the cruel plunderers had gone home, God gave strength to the survivors. Wretched people fled to them from all directions, as eagerly as bees to the beehive when a storm threatens, and begged whole-heartedly, ‘burdefining heaven with unnumbered prayers’, that they should not be altogether destroyed. Their leader was Ambrosius Aurelianus, a gentleman who, perhaps alone of the Romans, had survived the shock of this notable storm: certainly his parents, who had worn the purple, were slain in it. His descendants in our day have become greatly inferior to their grandfather’s excellence. Under him our people regained their strength, and challenged the victors to battle. The Lord assented, and the battle went their way.

From then on victory went now to our countrymen, now to their enemies: so that in this people the Lord could make trial (as he tends to) of his latter-day Israel to see whether it loves him or not. This lasted right up till the year of the siege of Badon Hill, pretty well the last defeat of the villains, and certainly not the least. That was the year of my birth; as I know, one month of the forty-fourth year since then has already passed.

(Winterbottom 1978: 28)

After a short-lived truce, the situation changed rapidly along with new invasions by the Saxons along the Thames valley and from the southern coast, starting already at the beginning of the sixth century. As Jackson (1953: 203–206) writes, relying here on the evidence from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the second half of the sixth century witnessed great expansion of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex, formed in the first half of the sixth century by the Saxon chiefs Cerdic and Cynric. By around 600, Wessex reached as far west as the River Severn, and further south, to the forest of Selwood on the borders of Wiltshire and Somerset. This meant that the Britons of Wales were cut off from the Britons of the south-west of Britain, leading eventually to the separation and division of the (Late) British dialects into Welsh and Cornish, respectively. After a brief respite of some fifty years, the kingdom of Wessex pushed further west, first conquering the remaining parts of Somerset, Devon and possibly parts of Dorset (although, as Jackson points out, the Chronicle has nothing to say about Dorset at this period), with the conquest of Devon being completed in the early decades of the eighth century. Cornwall remained in British hands for another hundred years, and according to Jackson (1953: 206) retained some form of independence, though probably sharing the power with the Anglo-Saxons in the final stages, up until the time of Athelstan, who was king of England from 925 to 939. Wakelin (1975: 67) provides a more detailed account of the Saxon settlements in Cornwall in 1086 on the basis of the Domesday Book. From this survey of tenure and population as well as the place-names recorded in it, Wakelin concludes that the north-east and south-east of Cornwall were firmly Anglo-Saxon by this time, with its nomenclature being mostly English; to the south and west of these areas, by contrast, the majority of the place-names and settlements were still Cornish (Wakelin 1975: 65f.). Yet, combining the evidence from Domesday Book and other sources, such as the Bodmin Gospels, written in the early tenth century, leads Wakelin to conclude that by 1086 the whole of Cornwall had already been brought under the rule of an Anglo-Saxon minority (Wakelin 1975: 67).

In the north of Britain, the Anglo-Saxon conquest proceeded similarly along major waterways such as the Trent and the Humber. Settlements in the north and the Midlands led to the establishment of the Anglian kingdoms of Lindsey and Mercia, respectively. The latter was rather weak at first, as Jackson (1953: 207) writes, and did not become a powerful kingdom until the second quarter of the seventh century. Under their king Penda (d. 655 AD), Mercia conquered large areas both from their West Saxon cousins in the south and the Welsh in the west. Jackson refers here to the often-expressed view according to which the Mercians also managed to reach the sea in the north and thus break the land connection between the Welsh and the Britons of the North. He does not, however, find any solid evidence to substantiate this claim; even the victory at the battle of Chester in 613 or 616 was won by the Northumbrians, not by the Mercians (Jackson 1953: 210–211). In any case, the Anglo-Saxon advances to the north proved to have significant consequences for the later development of the Celtic languages, as it meant an areal separation of the Welsh and Cumbric dialects of Late British.

The western expansion of Mercia under Penda and his followers also led to the establishment of the borderline between Wales and England around such landmarks as the River Wye in the south and the boundary earthwork known as Wat’s Dyke, running from the River Dee to near the town of Oswestry. This, as Jackson remarks, probably marked the western border of Mercia about the middle of the seventh century (1953: 211). Somewhat later, Wat’s Dyke was followed by another earthwork called Offa’s Dyke, raised by king Offa of Mercia in the late eight century. Its southern end was at the mouth of the River Wye, from which it ran via Hereford and Shrewsbury northwards, finishing near Wrexham. According to Jackson (1953: 211), Offa’s Dyke consolidated the borderline situation which had already been established for more than a hundred years earlier.

In the far north, the earliest Germanic settlements recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle were those under king Ælle, who reigned over the kingdom of Deira in the late sixth century. However, on the basis of some archaeological evidence Jackson dates the beginning of the Anglo-Saxon settlements to a period about a hundred years earlier, in areas of Yorkshire and in the city of York itself, which has one of the earliest Anglo-Saxon cemeteries in the whole country (Jackson 1953: 211–212). Jackson also refers to Hunter Blair (1947), who has sought to prove that the earliest Saxon settlements go back to the late Roman period and were in fact the result of a conscious Roman policy aimed at building an efficient defence against the continual raids of the Picts and Scots from the north. Whether Hunter Blair’s account fully matches the archaeological evidence remains open to question, as Jackson notes (op.cit., 212, fn.).1 In any case, there seems to be little doubt about the early presence of the Anglo-Saxons in the northern parts of the country.

Further north from Deira the Anglian invaders formed the kingdom of Bernicia, with Bamburgh as its centre. This seems to have taken place a little later than the founding of Deira. At the end of the sixth century, these two northern kingdoms were joined together by king Æthelfrith (593–617), giving rise to the powerful kingdom of Northumbria. Under Æthelfrith and his successor Edwin (617–633) Northumbria was able to greatly expand its area and eventually held the overlordship over the whole of England except Kent. During this period, the south-eastern parts of Scotland were also brought under Anglian rule, and by the middle of the seventh century, as Jackson writes, “the whole of south-east Scotland from the Forth to the Cheviots east of the watershed between Clyde and Tweed, Liddel and Tyne, was in English possession” (1953: 214). By contrast, it is less certain when the areas west of the Pennines were conquered by the Anglo-Saxons. Jackson treats with some scepticism views expressed by Ekwall and Stenton, according to which the occupation of large parts of Lancashire, Westmorland and Cumberland happened as early as the time of Æthelfrith, some parts of Lancashire even earlier, as Ekwall had suggested on the basis of a number of English place-names. Basing his own account on evidence discussed by Myres and Hunter Blair, among others, Jackson concludes that the process of occupation must have started about the middle of the seventh century but that the areas in question were not in English hands until the last quarter of that century (Jackson 1953: 217). He goes on to note that this was not by any means a final arrangement, as the British kingdom of Strathclyde continued to have a strong presence in the south-west of Scotland and was early in the tenth century able to recapture Cumberland, which was not won back by the English until 1092.

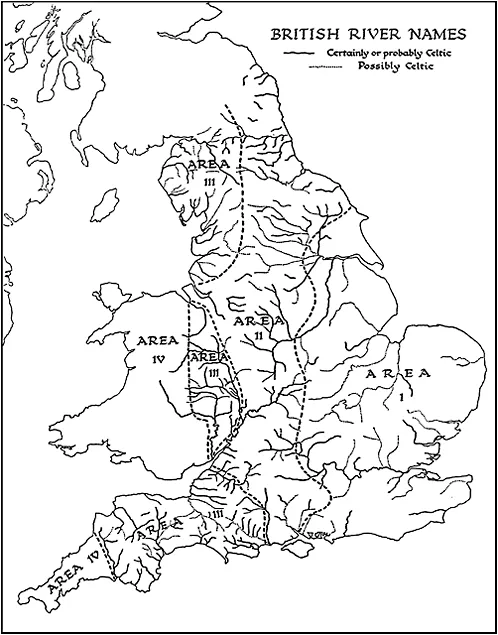

Summing up the advance of the Anglo-Saxon occupation, Jackson (1953) shows on the basis of river-name and other evidence how the Anglo-Saxon invasions proceeded in a wave-like process from the south and east towards the west and north (see Map 1.1 from Jackson 1953: 220).

Map 1.1 Four stages of the Anglo-Saxon occupation of England, based on evidence from Brittonic river-names (from Jackson 1953: 220). Reproduced by permission of The Four Courts Press, Dublin.

In Area I, as Jackson explains, Brittonic river-names are rare, and they are mainly those of large or medium-sized rivers, e.g. the Trent, the Thames, the Thame, and the Darent.2 Combining this evidence with other types of historical evidence leads Jackson to conclude that this area corresponds more or less with the extent of the first English settlements down to about the first half of the sixth century (op.cit., 221–222). In Area II, by contrast, Brittonic river-names are much more common, and the number of those with a certain Celtic origin is greater than in Area I. In settlement terms, this area reflects the advancement of the Anglo-Saxon occupation by the second half of the sixth century in the south and the first half of the seventh in the north (op.cit., 222). Area III, then, covers in the north those areas of present-day Cumberland, West...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Maps

- Abbreviations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- PART I Early Celtic Influences in English

- PART II Celtic Influences in the Modern Age

- EPILOGUE The Extent of Celtic Influences in English

- Notes

- Bibliography