1

A PSYCHOLOGIST BETWEEN LOGOS AND ETHOS

Joachim I. Krueger

Brown University

At the 17th Annual Convention of the Association for Psychological Science, Los Angeles, May 29, 2005, Robyn Mason Dawes was honored with a Festschrift conference. Following a convivial banquet on the eve of the Festschrift symposium, several of Robyn’s friends and colleagues presented papers on recent research that was, in one way or another, indebted to his intellectual inspiration over the years. This volume is composed of chapter-length reports of most of these research enterprises as well as some chapters authored by individuals who did not speak at the symposium. With characteristic modesty, Robyn requested that the contributors present their finest work and refrain from emphasizing his contributions to these efforts. It falls on this introductory chapter to provide the overarching context for these lines of research and a sense of Robyn’s abiding influence.

It is fitting to begin with a biographical note. Robyn entered the graduate program in clinical psychology at the University of Michigan in 1958. His stint in that program included some experiences that shaped his outlook on psychological science for years to come. Robyn noticed that clinical psychology was caught between the two frames of being seen as an art and a science. In his view, the latter was neglected. He found that scientific advances showing the limits of clinical diagnosis were being ignored. In one poignant instance, Robyn was asked to administer a Rorschach test to a 16-year old girl who had been admitted because of sexual relations with an older man, which had led to strained relations with her family. After analyzing the Rorschach protocol, Robyn found that just one of her responses to any of the Rorschach cards was “abnormal” (i.e., “poor form”). At a case conference, he argued that this low rate of nonstandard responding did not warrant a diagnosis of schizophrenia. In essence, his argument was that her performance was no different than what would be expected from base rate responding in the general population. If anything, her responses were more “reality oriented.” Robyn was overruled by experienced clinicians, who rejected his statistical argument. Mr. Dawes, he was told, you may understand mathematics, but you do not understand psychotic people (“Just look at the card. Does it look like a bear to you? She must have been hallucinating.”). With that, Robyn left the program and turned his attention to mathematical psychology.

In due course, his collaboration with his mentor Clyde Coombs and his cohort Amos Tversky led to the publication of the classic monograph of this field (Coombs, Dawes, & Tversky, 1970). Much of his own empirical work was henceforth dedicated to the detection of psychological distortions in human judgment (Dawes, 2001). From the outset, he did not single out clinical experts as victims of irrational thought but tried to understand general principles of mind that yield systematic biases in judgment. With this orientation, he placed himself in the tradition of Jerome Bruner and his colleagues, who had recently laid the groundwork for the cognitive revolution in psychology. Reaching further back still, the influence of Bartlett’s (1932) work on the role of narratives in remembering turned out to be relevant.

To Robyn, human reasoning occurs in both a narrative and a scientific mode. Narratives provide meaning, help remembering, and simplify otherwise complex quantitative input, yet these same narratives can systematically interfere with logic or statistical rationale. In his dissertation, Robyn presented his participants with declarative sentences representing a suite of set relations (Dawes, 1964, 1966). Some relations were nested, such as when all X were Y (inclusion) or when no X were Y (exclusion). Other relations were disjunctive, such as when some X were Y. Immediately after presentation, Robyn probed the participants’ recollections of these relations. As he had suspected, most participants were more likely to remember disjunctive relations as being nested than to remember nested relations as being disjunctive (and were more confident in their recall when it involved this error than when it was correct). In other words, he had not only identified systematic memory distortions, but he had correctly predicted which type of distortion was more likely to occur. From a narrative point of view, these distortions were benign in that they yielded mental representations that were simpler pler than the reality they meant to portray. From a scientific or paradigmatic point of view, however, these distortions were worrisome because they could lead to incoherent judgments and ultimately harmful action. As Robyn cautioned, “we may think of these people as one-bit minds living in a two-bit world” (Dawes, 1964, p. 457).

Misremembering disjunctive relations as being nested is an error of overgeneralization, a kind of error Robyn had already seen in action. Giving an “abnormal” response to a particular Rorschach card and being psychotic are instances of disjunctive sets. To say that everyone who gives this response is psychotic is to claim that the former set is nested within the latter. In time, Robyn approached these types of judgment task from a Bayesian point of view. Harkening back to his earlier experience with clinical case conferences, it could be said that the clinicians began with the idea that there was a high probability of finding evidence for an offending response if the person was ill (i.e., p[E|I]). Their diagnostic judgment, however, was the inverse of this conditional probability, namely, the probability that the person was ill given that one abnormal response was in evidence (i.e., p[I|E]). Meehl and Rosen (1955) had shown that base rate neglect pervades human judgment in general and clinical judgment in particular. Inasmuch as the base rate of making the response, p(E), is higher than the base rate of being ill, p(I), the probability of illness given the evidence from testing can be very low indeed.

Along with his friends Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, Robyn stimulated the growth of the psychology of judgment and decision making. Whereas Tversky and Kahneman documented the base rate fallacy in a series of widely noted experiments (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974), Robyn discussed numerous examples of non-Bayesian thinking in his writing. His 1988 book, Rational Thought in an Uncertain World (see also Hastie & Dawes, 2001, for a revised 2nd edition; a 3rd edition is in preparation), is a classic exposition of common impediments to rationality. His critique of clinical psychology and psychotherapy (House of Cards [Dawes, 1994]) is the authoritative application of the principles of judgment and decision making to that field. Robyn’s empirical work yielded a report in which he and his collaborators presented a rigorous correlational test of the overgeneralization hypothesis (Dawes, Mirels, Gold, & Donahue, 1993). Unlike Tversky and Kahneman, who provided their participants with base rate information, Robyn and his colleagues asked their participants to estimate all four constituent Bayesian probabilities themselves. This within-person method yielded strong evidence for overgeneralization. When estimating p(I|E), participants neglected the base rates of p(E) and p(I) that they themselves had estimated. Instead, they appeared to derive p(I|E) directly from p(E|I). Bayes’s theorem states that the two inverse conditional probabilities are the same only when the two base rates are the same (which they were not for most participants). In Robyn’s analysis, people assumed a symmetry of association that is rare in the real world.

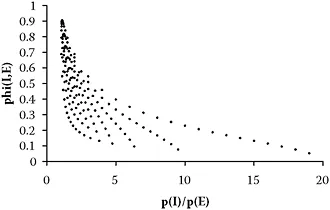

Associations between variables are often represented as correlations. One may want to predict, for example, illness versus health from positive versus negative test results, yet a perfect correlation can only be obtained when the two base rates are the same. Overgeneralization becomes more likely inasmuch as the base rate of the diagnostic sign is larger than the base rate of the underlying illness. It is worth considering a numerical example. Suppose a certain test response is rather common (p[E] = .8), whereas the underlying illness is rare (p[I] = .3). The ceiling for the correlation between the two is .327. Even if everyone who is ill emits the response (i.e., p[E|I] = 1), the inverse probability, p(I|E), is only .375. The former probability expresses the sensitivity of the test, or how typical the response is of the underlying disposition. The inverse probability, however, also depends on the ratio of the base rates. According to Bayes’s theorem, p(I|E) = p(E|I) p(I)/p(E), where p(E) = p(I)p(E|I) + p(−I)p(E|−I). In other words, p(E) depends greatly on the probability of the evidence given the absence of the illness (which, in turn, is the complement of the test’s specificity, or 1 − p[−E|−I]). This is what people neglect to take into account and what leads them to confuse pseudo-diagnosticity with true diagnosticity.

As the predictive validity of a test can be expressed as the correlation between test results and actual health status, this Bayesian analysis shows that the ceiling of validity coefficients becomes lower as the two base rates become more discrepant. In Figure 1.1 the maximum correlations are plotted against the ratio of the base rates. Data for this illustration were constructed by letting p(I) range from .05 to .95 and letting p(E) range from .05 to p(I). Across the simulated instances, the correlation between the base rate ratio and their maximum statistical association is −.65. When the natural logarithms of the ratios are used to reduce the biasing effect of nonlinearity, this correlation is almost perfectly negative (r = −.81).

The irony of this result is that a mere increase in positive test responses may be seen as an improvement of the test when in fact its diagnostic value drops even when the test’s sensitivity remains the same. This example can be extended to current research on prejudice, with the variables I and E, respectively, denoting implicit and explicit attitudes. Research with the implicit association test (IAT; Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwarz, 1998) routinely shows large effect sizes for implicit bias and

low to moderate correlations between I and E. As the high values of p(I) are hailed as important evidence for how many people are really prejudiced, it is overlooked that the same finding reduces the predictive power of the test. In clinical assessment the reliance on pseudo-diagnosticity is particularly fraught with danger because a person’s true status is difficult to ascertain. Ultimately, criterion judgments about underlying conditions are also clinically derived. Such judgments are notoriously elastic, as they allow, for example, speculative assessments of a person’s latent (i.e., not overtly expressed) pathological disposition.

To Robyn, social responsibility demands that people, and presumed experts, be disabused of associationist thinking. Ultimately, his outlook is optimistic. He defines rational thought as the avoidance of contradictory beliefs. A set of beliefs or inferences is rational if it is coherent, and to insure coherence, it is necessary to make comparisons. In Bayesian language, drawing inferences from the ratio’s numerator alone is associationist and bound to be incoherent. In contrast, drawing inferences from comparisons avoids contradiction. Often, associationist thinking is considered primitive and automatic, whereas comparative thinking is controlled, effortful, and resource-consuming. Robyn generally agrees with this view, but he suggests his own characteristic metaphor. As a young man, he taught children in a summer camp to swim. He noticed that the kids instinctively tried to keep their heads above water, which moved their bodies into a vertical position, thereby making drowning more likely. To help them overcome their fear, he had to teach them to keep their faces beneath the waterline and come up for air only periodically and rhythmically. As all swimmers know, this new attitude quickly becomes second nature, and so it can be with rational thinking, according to Robyn.

Of course, proper comparisons require the presence of all the necessary information. Sometimes people do not have access to that information but act as if they do. To illustrate, Robyn extended Tversky and Kahneman’s notion of the availability heuristic to incorporate what he termed a “structural availability bias” (Dawes, 2005). Again, a clinical example is instructive. Robyn observed that many clinicians claim that “child abusers never quit on their own without therapy.” All that clinicians know, however, is the probability with which child abusers stop given that they are in therapy. The probability with which abusers stop without being in therapy is out of view. When the proper input for rational judgment cannot be obtained, Robyn advised suspending judgment, an insight that is as indicative of his genius as it is counterintuitive.

Another inspiration Robyn drew from Tversky and Kahneman’s work is the gambler’s fallacy. In Rational Thought in an Uncertain World (Dawes, 1988) Robyn illustrated this bit of irrationality with a letter to Dear Abby, in which the writer insisted that the law of averages [sic] demanded that a baby boy was due after five consecutive baby girls. Whereas the gambler’s fallacy is easily explained statistically and equally easily demonstrated empirically, the field of psychology has sorely bee...