1 The past and the other in the present

Kokunai kokusaika kanko—domestic international tourism

Nelson Graburn

With a candor far removed from the usual poetic fog of the imperial court, Emperor Akihito, in remarks to the news media that took Japan by surprise in December, all but declared his own Korean ancestry. Speaking of the culture and technology brought to Japan … [he] said that ‘it contributed greatly to Japan’s subsequent development.’ Then, he added, ‘I, on my part, feel a certain kinship with Korea,’ and went on to cite an ancient chronicle that says that the grandmother of his eighth-century imperial ancestor, Kammu, was from a Korean kingdom.

(Howard W. French, New York Times, 11 March 2002)

Introduction1

It is not often that, in my career as an ivory tower social scientist, I have been scooped by a member of the imperial family. This quote refers to a particular strand in the complex phenomenon of Japan’s relations to outside peoples and nations, the cultural and now it appears ‘filial’ ties between Japan and Korea. This particular strand has been neglected, avoided and denied by most Japanese until recently (DeVos and Lee 1981; Ohnuki-Tierney 1990). The story that I relate here involves two places where the relations of Japan to Korea in the historical past—one where Koreans settled in Japan four centuries ago, and the other more than 1,300 years ago—have been recognized and promoted for a complex set of reasons, and whose present sites are the targets of domestic and international tourism.

The point in this experimental chapter on tourism and foreignness is to show how the usual construction of spatial identity by which places and regions get themselves ‘on the map’ (Graburn 1995) has been expanded by the inclusion of domesticated foreignness. In this case we may reverse Lowenthal’s dictum (Lowenthal 1985) by stating that ‘a foreign country is the past’. In this case the insertion of Koreanness into the structured panoply of meibutsu (things to be famous for) has reflected with both the ideological trend towards liberal multiculturalism in Japan (Graburn 2002, 2003; Graburn et al. 2007; Lie 2001) and pragmatic responses to Koreans’ emergence as the leading sources of foreign tourists entering Japan since the early 1990s. A unique feature of one of the following cases is the asserted connection between core features of Japanese culture and antecedent features coming from Korea and the implied relationship between the Korean connection and the mythological, archaeological and historical origins of Japan’s imperial family.

Those aspects of Chineseness and Koreanness coming from the dawn of Japanese civilization are not commonly recognized as ‘foreign’ except in the analytical sense. Foreignness consists of the frequent and remembered incursions and borrowing from the outside world within recorded history. Until the Tokugawa shoguns closed Japan at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Japanese were often in trade (or at war) with overseas civilizations, and the Japanese countryside is marked with sites and memories of these contacts. Historically remembered events or sites are part of the fabric of today’s Japan; most places have special events or products which contribute(d) to the organic whole. Thus each location has one or more allegedly unique characteristics, meibutsu (things it is famous for), which are key tourist attractions, even if they are non-Japanese (cf. Hendry 2000 for a slightly different version of foreignness as Japanese). It is the uniqueness of a place that is its particular part in ‘making Japan’ (Wigan 1997). Thus different areas are known by different events, characteristics and products.

It happens that the southern island of Kyushu ‘is unique’ for its multiple non-Japanese historical events and characteristics. According to a typical Japanese guidebook for domestic tourists (Ikuchi 1999: 18), ‘Kyushu has always been a window on other cultures’, i.e. its ‘near foreignness’ is its meibutsu, the thing for which it is famous within the Japanese system.

This is particularly true of the southernmost daimyoship, known as Satsuma province (centred on but covering more than present-day Kagoshima), which is famous not only for spearheading the revolution which toppled the shogunate and put the emperor back on the throne in 1868, but also for its long history of foreign contacts. Some people of that area today are proud to say that they were far from Tokyo and Kyoto so their daimyo could get away with things that other Japanese could not.

Miyama: domesticated Koreanness

Prime among the historical evidence of foreignness and hence the sources of many ‘foreign attractions’ for domestic tourists are: Christianity, brought by the Portuguese Jesuits led by Saint Francis Xavier (Nagai 2001; Turnbull 1996; Whelan 1997) in the fifteenth century (leading eventually to their expulsion and the ‘closing’ of Japan); the long history of trade and eventually incorporation of the Ryukyuan kingdom of Okinawa in the eighteenth century, a direct source of trade and products from China and South-East Asia; and the Imjin War when Shogun Toyotomi Hideyoshi invaded Korea in the 1590s. The seventeenth daimyo, Shimazu Yoshihiro of Kagoshima, accompanied Hideyoshi to Korea and, when the invasion was eventually repelled, he had 80 Korean potters brought back with him. They were set up in three towns in Satsuma where there were suitable clays and minerals, in order to produce superior porcelain and pottery, known as Satsumayaki, as sumptuary goods for the daimyo and nobility. This ‘stolen’ Korean tradition is so important to Koreans that the invasion is sometimes called the ‘pottery war’, especially as Korea lost its best traditions and skills in later history (Geon-Soo Han, personal communication, 2000).

The town of Miyama (Beautiful Mountain), formerly known as Naeshirogawa, about an hour’s drive west of Kagoshima City, is famous for two phenomena of ‘national’ importance. Firstly, it is the site of the manufacture of Satsumayaki, a distinctive kind of pottery characteristic of Satsuma (see above), in its 14 working kilns. Secondly, there is a memorial hall dedicated to the life and works of the infamous former minister of foreign affairs in the Pacific War, Togo Shigenori2 (Ikuchi 1999: 336–7).

There are two major forms of pottery produced in Miyama today. The more famous and expensive form is called ‘white’ Satsumayaki, which includes pottery with painted decorative motifs over a ‘crackled’ golden-yellow base colour; it looks distinctively Japanese yet, when compared with now more popular and stereotypical, stark, shibui (simple yet refined) asymmetrical pottery, one might suspect some Chinese influence. For even less utilitarian purposes there is another more purely white unpainted form of pottery, usually in the form of sculptural figurines rather than dishes. In the less expensive register is ‘black’ Satsumayaki, which the promotional brochures say ‘is widely cherished among the common people [consisting of] items such as tea pots, tea cups and such … deeply rooted to the people’s daily lives’. Of course many readers will recognize such phrases as reminiscent of the language of Yanagi Muneyoshi, who ‘created’ the idea of the artless peasant craftsman and popularized his mingei (folk art) products (Moeran 1981). Like nearly all such contemporary pottery in Japan, it is consumed by middle-class urbanites for its slightly nostalgic ‘furusato-like’ (like the rural village community where most ancestors of the Japanese originally came from) qualities.

Primus inter pares among these 14 potters—all of Korean descent—(and one guitar maker) in the village is the ‘house’ of Jukan Toen (Jukan Chin Satsuma ware factory).

When one enters the formal gate of the huge compound of old-fashioned wooden houses which constitutes the ‘factory’, one is greeted by masts with equal-sized flags, Japanese and Korean, flying side by side. Further inside, one of the side buildings is labelled ‘Honorary Korean Consulate’. The major garden decoration is a large white-flowering bush, the mugunghwa (hibiscus syriacus), the national flower of Korea.3

The publicity tells that for 400 years the enterprise has been run by a Korean family, the Chin Ju Kan family (Shim Su Kwan in Korean), of which the present head goes by the ‘professional’ name Shim Su Kwan XIV. Since my first visit there in summer 2000, he has passed the baton on to his son Kazuteru Osako, now Shim Su Kwan XV.

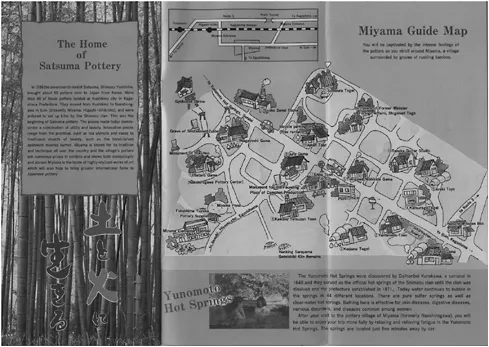

Figure 1.1 English-language tourist map of Miyama (note Jukan Toen on the main street).

These ‘professional immigrant’ families used to wear Korean dress up until the beginning of the Meiji period (1868–1912), and they used the Korean language even longer (Brian Moeran, personal communication, 2002). The Shim (also named Osako) family remained under the Shimazu patronage for nearly 300 years. After the opening of Japan their wares were shown at European expositions, where the daimyo often mounted his own Satsuma pavilion (Graburn 1991: 241) and exported through to the 1870s. However, as the daimyos were divested of their landed property, their sponsorship ceased in 1875 and the family had to go it alone. Shim Su Kwan XII restored the technique and reputation of Satsumayaki, and found or renewed patronage by nobility and rich buyers abroad. He was suitably rewarded with a distinguished service medal from the export-minded Meiji government in 1885. He even gained the patronage of the imperial household and was visited by the prince and princess in 1893. One book emphasizes that Shim Su Kwan XIV ‘contributed significantly to cultural exchange and goodwill between Japan and Korea’ (Chinjukan 2001) and was the first Japanese to be appointed as the honorary consul-general of Korea.

In 1998 he planned and promoted the four-hundredth anniversary of Satsumayaki and was lionized after an exhibition in Seoul, where he received Korea’s highest cultural award, the Silver Crown medal of the Order of Culture. Shim Su Kwan’s pottery exhibition in Seoul drew 50,000, and was accompanied by many articles, a book, and visits by many upper-class people and government officials to Miyama (Geon-Soo Han, personal communication, 2000). On the four-hundredth anniversary of the arrival of the original 80 potters by ship, the town was unusually bustling; a Korean reproduction of a sixteenth-century sailing ship came directly from the Korean coast, bringing ‘fire’ from the supposedly original pottery kilns there. When Korean potters carried the ‘sacred fire’ to Miyama, they were, according to Korean reports, reclaiming the pottery tradition by asserting that the kilns were now fired by Korean flames. The Japanese newspaper said this was the ‘fire of friendship’.

Naturally, the Higashi Ichiki town office, within which Miyama falls, has latched on to these distinctive traditions, alongside its other attractions, including the Yunomoto onsen, the birthplace of Boku Heii, the grave of Shozaemeon Zusho and, of course, the commemorative hall celebrating the former minister of foreign affairs in the Second World War, Togo Shigenori.

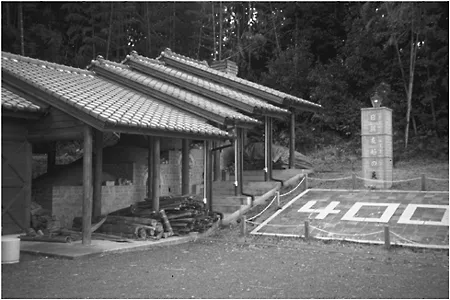

To draw attention to the centrality of pottery in the village and regional identity, they built an imposing multi-purpose community centre beside a restored old noborigama (climbing kiln) on a small hill near the centre of Miyama (Naeshirogawa Pottery Center on the map in Figure 1.1). Between the centre and the old kiln is the memorial proclaiming 400 years of Korean-Japanese friendship, consisting of hundreds (perhaps 400) of clay tiles each with the hand impression of a child with its name (all Japanese as far as I could make out). Next to the hands-on clay memorial is a larger wooden plaque in Nihongo (the Japanese language) and hangul (the uniquely Korean form of syllabic writing) recalling the glorious relationship, erected by the Japan-Korea Friendship Society, of which our family leader, Nozoesan,4 was an active member.

The large wooden building that serves as the community and tourist centre has in one large room pottery wheels and a kiln, for the use of amateurs such as schoolchildren, old people and tourists. It also has an impressive permanent exhibition of local pottery, as well as a gallery of local products and a shop selling ceramics as omiyage (souvenir gifts) and serving refreshments.

Preceding my second visit, in 2002, Shim Su Kwan XIV and his pottery were featured in the World Ceramic Exposition 2001, held in Ichon, Korea, which was the site of the Japanese-Korean revival of classical Korean pottery in the 1920s (Moon 1997). Already renowned in Korea, he was accompanied from Japan by a number of delegates from the Japanese-Korean Friendship Association from the Kagoshima area. And, expectedly, Korean-language travel literature on Japan features this ‘local hero abroad’ as one of the main attractions of the island of Kyushu.

The second paragraph in the Korean-language pamphlet is the statement that the Seoul-based Korean baseball team, the Lotte Giants, have been staying at the nearby Yunomoto onsen hot spring resort as their training camp since 1990! This inclusion of multiple attractions in the ‘selling’ of Japanese tourist locations is typical (Graburn 1983, 1995), as seen in the Miyama map (Figure 1.1), which ‘sells’, alongside Satsumayaki, not only the old historical sites mentioned above but the local shrine, the guitar studio, the Togo Shigenori hall and the (road to) the Yunomoto hot springs. In the same way, the Korean-language pamphlet emphasizes the multiple ‘Korean’ attractions of the region, at the same time ‘familiarizing’ the atmosphere with the name of a ‘home’ team.

Figure 1.2 Four hundred years of friendship memorial next to noborigama (climbing kiln).

Koreanness emergent

Now let us step back nearly another thousand years to the tourist site of Nango Son (village) in Miyazaki prefecture, where allegedly the defeated seventh-century emperor of the Paekche (Kudara) kingdom sailing from the Korean peninsula found refuge in the village of Nango 40 kilometres inland from the ancient town of Hyuga on the south-east coast of Kyushu (Ikuchi 1999: 290–1). Hyuga itself recalls an almost pre-nostalgic past, for it is the present-day bearer of the surviving name of the ancient province of Hyuga, which was to the present prefecture of Miyazaki what Satsuma was to the prefecture of Kagoshima. As one follows the twisted road inland, up the valley from Hyuga, all the road signs are in Japanese and Korean hangul syllabic characters.

As one arrives in the small village of Nango and turns into the broad car park between the main road, running along the bottom of the hillside, and the small river which forms the other boundary, one can see the annai, the signboard showing the major tourist features of the place: the Kudara Restaurant, Kudara no Mori (the Mikado Shrine), the new ‘Western Shosoin’5 and the Paekche Palace. This small village once had a population of 7,000, but, as is typical in rural Japan (Graburn 1997), it suffered a continuous exodus and by 1990 this had dropped to 3,000; by 2002 it was about 2,500.

The Nango Restaurant is constructed in a modern ‘retro-style’ typical of country eating places—black beams and white registers with unpainted wooden pillars inside. Although it has ‘Korean hot tables’ in the middle for Korean foods, it has other attractions than Koreanness, for in Korean cuisine the menu actually only runs to something like ‘Kimu Chi Setto [set meal with the Korean pickled vegetables kim chi]’, but it also advertises other local delicacies including a unique delicacy called kodawari made of...