![]()

1 Introduction

The Growth and Context of Tourism in China

Chris Ryan and Gu Huimin

INTRODUCTION

This book is about tourism in China and the context within which Chinese tourism develops—a context that is formed by a wish to lift many millions out of poverty, a need for economic growth, a political system that is in transition with a dismantling of statism to form a socialist market system with a Chinese perspective, and a culture still imbued with Confucian values yet influenced by Buddhism, Taoism and Maoism. To concentrate upon the purely touristic without reference to these wider frameworks would lead to an incomplete understanding of tourism development in China today. Such developments are seen ‘on the ground’, and thus this book concentrates upon destination developments and policies with reference to tourism.

The Chinese data relating to the growth of tourism are generally well known in terms of the rates being exceptional with the outcome that within a few decades China will not only be the major tourist generating country in the world but also the major tourism receiving destination. However, as noted in the following, much of the current tourism flows are intraregional, and thus some caveats have to be noted with reference to such predictions. A brief review of those data and the accompanying growth in hotel accommodation is provided in the following, but impressive though the figures are, the wider context needs to be established if one is to understand the motives that lie behind these developments, and their implications. For all of the high-rise architecture of Shanghai and Shenzhen, and the impressive buildings associated with the Beijing Olympics, China remains, at least for the moment, a developing country. While the populations of its major cities number in total about 76 million and thus exceed the populations of many countries, and its total urban population was estimated at 562 million in 2007, thus far exceeding that of the United States (approximately 305 million in 2007), in the rural areas almost a further 767 million people live, and for many of them the promise of economic development has yet to arrive. In 2005 the average annual disposable rural per capita income was 3,255 RMB, that is approximately US$400 a year. Not that all living in the urban areas enjoy much higher standards of living, for again in 2005 the mean average per capita urban disposable income was 10,493RMB (US$1,281). Yet any visitor to Shanghai or Beijing will see as many expensive cars as in London, Paris or any other major global city while the luxury car manufacturers see China as a market with an exciting future. The nature and speed of development in China, and the stresses it involves can be traced in the movement of population from the rural areas to the urban. In 2001, 64 per cent of the population lived in rural areas, by the end of 2006 that figure was 56 per cent (data derived from State Statistical Bureau of China—http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/). However, such changes are not solely due to rural emigration. There is also the physical enlargement of the cities themselves as in their growth they encroach upon once surrounding countryside.

THE CONTEXT OF TOURISM POLICIES IN CHINA

Poverty alleviation is thus a driving motive behind much of China’s economic development and strategies. In 1996, at a speech at the Central Work Conference on Poverty Eradication on 23 September, the then premier, Li Peng, declared that the country would see an end to poverty in its rural areas by the end of the century. This objective meant the lifting of more than 65 million people out of poverty (Gustafsson and Zhong 2000). Gustafsson and Zhong proceed to note that poverty is very much associated with location. Poverty is very much associated with rural areas, with mountainous areas and being in the west. Wealth is associated with the cities of the Yangzhi River delta, Pearl River delta and eastern coastal areas.

The new affluence is thus unequally distributed, as are the opportunities to acquire such wealth. The reforms introduced after the Fall of the Gang of Four and the ushering in of the ‘Open Door’ policy has meant radical changes in the fortunes of many, but it is marked by unequal spatial, generational and educational opportunities. Younger people tend to gain advantage, and access to higher education becomes a key to affluence, thereby explaining the annual tension of university entrance examinations in China. Yet arguably it is the economic revival of the rural areas that helped China initiate the economic boom that is seen in the early decade of the twenty-first century. An important mechanism ushered in by the reforms enacted between 1978 and 1983 was the end of collective farming and the restoration of private ownership of land (Peng 1999), although land can still remain in village collective ownership effectively controlled by local political structures. As described by Gu and Ryan in their chapter on Hongcun and Xidi, and Zhou and Ma in their chapter on Baiyang Lake, this collective village entrepreneurship and Township and Village Enterprises (TVEs) (or xiangzhen qiye) came to be important in the development of rural-based tourism initiatives. Indeed, more generally, as described in Chapter 15, the TVEs were an important contributor to GDP until the latter part of the 1990s when banking practices began to change. However, Peng (1999) argues that the land reforms tended to produce a one-off economic impetus because although rural production rose, food prices tended to remain relatively flat for long periods with exceptions as in 1987–1989, and again in 2006–2007 when pork production was affected by swine fever and inflationary pressures began to be exerted in the Chinese economy. Given these slow increases in rural incomes, it is not surprising that small-scale tourism rural enterprises emerged based primarily on farm stays and bed and breakfast accommodation that had easy access to major urban populations. Important keys that account for the success in the removal of so many people from poverty include migration to the cities and expatriation of monies back to rural family members as in the population rural–urban distribution noted earlier, and second, especially prior to 1995, the encouragement and emergence of rural enterprises as discussed in Chapter 15. Today China’s domestic private sector or non-state sector is now used to include the following entities: (a) TVEs; (b) small-scale household enterprises or family businesses with fewer than eight employees (getihu); (c) private businesses with eight or more employees (siren qiye); (d) state-owned enterprises (SOEs) that have been privatized; and (e) publicly listed joint stock companies. Excluded from this definition are firms completely owned by investors from Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan, and joint ventures formed by these investors with their partners in China (Li 2005; Tsui et al. 2006). Hence another contextual theme within which tourism development needs to be located is the dismantling of statism, as is discussed in Chapter 8. This is evident at many different levels. For example, at the time of writing the 11th Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) was taking place (March 2008). In the government work reports by Premier Wen Jiabao and Jia Qinlin, the chair of the 10th CPPCC, several references are made to the development of a socialist market economy with Chinese perspectives, and the need for socialist responsibility on the part of private sector entrepreneurs.

With reference to the evolution of a socialist market economy with ‘Chinese characteristics’ a debate exists as to the real reasons for Chinese economic growth. Woo (1999) entitles competing schools of thought as the experimentalist and convergent, and comments past research has tended to find that economic growth almost always accompanies the dismantling of any centralized state. Woo’s analysis is based in part on the performance of TVEs not categorized as being in the private sector, but one problem that is noted in the processes of classification is that categorization was and is not, in itself, always an accurate guide to the de facto situation of ‘on the ground’ ownership, especially in the period prior to about 1995. Chen (2000) draws upon the distinctions and interactions between de jure and de facto owner-ship of TVEs in his analysis of China’s market liberalization. Be this as it may, given the lack of importance attributed to tourism prior to 1978 and the commencement of economic reform, the tourism sector was able to fully take advantage of the trend towards freedom from state control, but did so within the ‘birdcage’ of centralized planning. Tourism has thus gained from Chinese entrepreneurialism within the Chinese socialist market system, and as will be discussed within the book, one key emergent theme has been a role assumed by rural communities, albeit one primarily motivated by a need for economic growth.

A further context is the recognition of minority peoples and religious minorities within China. It is part of the concept of a harmonious Chinese socialist state that these peoples are recognized and brought into a harmonious relationship with the Chinese state. Thus, as illustrated in this book, various initiatives exist to endorse tourism as a means of economic growth, but a key issue remains, namely that of recognition. The recognition of minorities such as the Bai or Sani peoples, or of the Buddhist and Taoist faiths, for tourism purposes possesses advantages for destination promotion and economic revival, but the aspirations of such peoples may not be constrained within a touristic–economic dimension alone. Any review of the literature of indigenous-based tourism in other countries reveals a linkage between tourism patronage and the use of tourism as a legitimization of cultural, economic, social and political aspirations (e.g. see Ryan and Aicken 2005). The Chinese government thus seeks to develop well-being for its various peoples as a whole, and to a western eye there may appear longer term difficulties as minorities may seek further rights beyond the purely economic, as became evident in Greater Tibet in March 2008. To argue from this that potential problems lie in the future becomes an evident pattern of potential discourse, but it needs to be remembered that Buddhism, Taoism and the different minority peoples share cultures that tend to the collective, and share a similar understanding of harmonious relationships. Given this, the official statements of harmonious development within a socialist market system becomes possibly less paradoxical, yet more nuanced, than would be understood in western societies, and also perhaps generates ways forward for peaceful development.

Another context that must be considered if one is to understand tourism in China are the very levels of economic growth that have been achieved. As Weymes (2007) describes, in 1983 a visitor to China would have found Beijing airport in desperate need of maintenance, a poor road connecting the airport to Beijing, and in Beijing itself, little traffic. In 2008 the city hosted the Olympic Games, state-of-the-art buildings existed and traffic congestion was a problem for the Beijing Olympic Games Organizing Committee. In 1978 there were only 137 star classified hotels in the country. Today more than 18,000 exist (CNTA 2007). For each of the last 30 years China has achieved GDP growth of over 9 per cent per annum. Foreign trade has averaged a 15 per cent annual growth rate over the same period, and the economy is now one of the largest in the world. Commentators speak of the twenty-first century as the Chinese millennium (Naisbitt 1995). China is, after all, the Middle Kingdom from the Chinese perspective, and thus will stand as the central point in a global network of business interests. One consequence of this is the growth of domestic and Chinese outbound tourism.

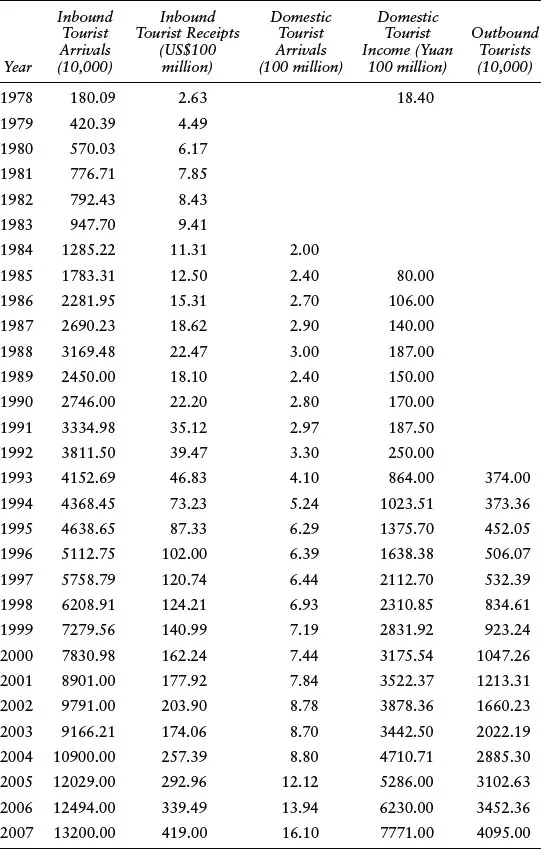

With reference to inbound tourism, in 1996 51.3 million visitors were hosted, and these visitors spent 10.2 billion RMB. By 2007 total tourism income exceed 1,000 billion RMB for the first time with an average increase of 22.6 per cent. In the same year the inbound visitors numbered 131.87 million and the first estimates of visitor expenditure indicated total spending of about 35 billion RMB (CNTA 2007). The main markets, (other than Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan which continue to dominate the statistics), by numbers of visitors in 2007 were Japan (3.7 million), South Korea (3.9 million), Russia (2.4 million) and the United States (1.7 million) (CNTA 2007). Domestic tourism numbered 639 million traveller arrivals in 1996, and an estimated 1,610 million in 2007 involving an expenditure of 777.1 billion RMB. The pattern of growth has almost been unbroken, other than in 2003 with the crisis of SARS, but in 2004 growth rebounded quickly. With reference to outbound tourism, in 1995 4.5 million Chinese tourists travelled overseas, and a decade later that figure had increased to 31 million. In 2007 the figure had climbed to 40.95 million with an average increase rate of 18.6 per cent which made China the number one tourism generating country in Asia (CNTA 2007). Impressive though these figures are, predictions that China will be the leading tourism generating country by a given date need to be tempered by the actual patterns of travel. Much of this travel is accounted for by travel to Hong Kong (which in many instances are day trips), Macau and other bordering countries such as Russia. The longer stay visitors tend to travel on package tours, and these account for about one-quarter of all private trips (G. Zhang 2006). Indeed, Hong Kong and Macau together account for about 70 per cent of all outbound Chinese tourism, and other Asian nations account for about 20 per cent of that tourism. Only about 5 per cent of outbound Chinese tourists visit Europe, and approximately the same amount visit North America, and of these many are on official business. Another sector of importance here is a VFR market involved in visiting relatives who are studying overseas (see Table 1.1).

To summarize, economic growth has helped to create a marketplace for tourism. A newly emergent, younger, professional, often western-educated and urban-market segment has emerged that wishes to emulate the consumer spending of their western counterparts. This is, however, in spite of appearances, more than a simple replication of the purchasing of consumer goods, as the ties of family responsibilities remain high, and, especially for those who gain access to urban wealth from rural areas through the portals of higher education, an awareness of the sacrifices made by parents must weigh heavily on their minds. Confucian mindsets of respect and familial duty are still present in Chinese society, and the current middle-aged beneficiaries of the reform policies exist as a generation in transition that seeks the best for its children while recognizing the role of their parents. As stated in different chapters in this book, studies of Chinese visitors, both domestically and internationally, show a socio-economic bias in the samples. They tend to be under the age of 45 years, tertiary educated and coming from the upper-income groups in China. The social changes are, however, significant and commentators like Weymes (2007) observe distinct generational differences beginning to emerge.

Table 1.1 Tourism Statistics in China

Source: Adapted from CNTA, Yearly Tourism Statistic Book, 1979–2007.

TOURISM AS A CREATOR OF ECONOMIC GROWTH.

It has been noted that tourism in China has emerged as a result of economic growth. However, over the last decade the growth in domestic and inbound tourism has tended to be faster than the overall rate of economic growth with, for example, CNTO (2007) data on international arrivals providing evidence of fast growth rates, such as in 2004 with a growth rate of 47.87 per cent in the rebound from the SARS-affected tourism of the previous years. Indeed, for the period since 1978, international arrivals have exceeded 15 per cent per annum in 16 of the 28 years to 2005. Given this it can be asked if tourism itself has become a contributor to economic growth. This is an especially pertinent question if one of the motives for tourism policies is the relief of poverty and low incomes.

Many studies have found strong contributions to economic growth that emanate from tourism development. In a study of OECD and non-OECD countries Lee and Chang (2008) developed a model of economic and tourism growth based on cointegration tests. They concluded that ‘unidirectional causality relationships exist from tourism growth to economic development in OECD countries, but bidirectional causality relationships are … found in non-OECD countries’ (Lee and Chang 2008: 191). They also found that the relationships are weaker in the case of Asian than non-Asian countries. The work of Kim, Chen and Jang (2006) in Taiwan independently supports these observations, for they found a mutual bidirectional relationship between tourism and more general economic growth in the case of Taiwan. In a Spanish context Parilla, Font and Nadal (2008) examine the issue of perceived lower productivity rates in tourism and the degree to which these lower productivity rates might inhibit longer term economic growth. They find that specialism in tourism in areas of Spain like the Balearics and Canary Islands has been a driving force for development, but longer term economic growth is dependent upon linkages between the tourism industry and other economic sectors, and the nature of diffusion effects and technology transfers. They also note that the public sector, mainly education, research and infrastructures, is also a key to sustained increases in productivity. They conclude that ‘the problem does not lie in the abundance of natural resources nor in specializing in tourism per se, but rather in the failure of economic agents to attend to the determinants of long-term growth. Thus, public policies must be aimed at palliating the lower growth in productivity that stems from the productive specialization itself and correcting the low propensity of economic tourism to address innovation and education’ (721). There is reason to believe that as the Chinese economy matures the same issues will arise. Namely that tourism is a generator of economic growth, but its longer term capabilities and productivities rest on its incorporation into wider economic systems including those provided by the public sector.

INTRODUCTION TO THE BOOK

Arising from these contextual issues this book will consider problems and management practices in China with reference to destinations and their planning. The book is divided into three main themes, namely ‘Destination Change and Planning’, ‘Destinations and Cultural Representations’ and ‘Community Participation and Perspectives’. Almost inevitably there is some overlap between these three themes, but the various contributions tend to possess different emphases that justify these distinctions. Each section is introduced by a separate chapter that picks up the contexts outlined here and which then serves to establish a context within which the following chapters provide case studies, illustrations and conceptual materials. A number of these chapters also provide further information about structural processes current in China.

The first section, ‘Destination Change and Planning’ comprises, after the introduction, two specific studies on China’s National Parks. One relates to issues of efficient use of resources, and the role of proximity as creating external economies of scale, while the second utilizes theories of destination development and spatial patterns to illustrate how economic growth emanating from tourism growth can have potential negative environmental and social impacts. Other chapters pick up similar themes. Thus the cha...