1 Benefits of testing memory

Best practices and boundary conditions

Henry L. Roediger, III, Pooja K. Agarwal, Sean H. K. Kang and Elizabeth J. Marsh

The idea of a memory test or of a test of academic achievement is often circumscribed. Tests within the classroom are recognized as important for the assignment of grades, and tests given for academic assessment or achievement have increasingly come to determine the course of children’s lives: score well on such tests and you advance, are placed in more challenging classes, and attend better schools. Against this widely acknowledged backdrop of the importance of testing in educational life (not just in the US, but all over the world), it would be difficult to justify the claim that testing is not used enough in educational practice. In fact, such a claim may seem to be ludicrous on the face of it. However, this is just the claim we will make in this chapter: Education in schools would greatly benefit from additional testing, and the need for increased testing probably increases with advancement in the educational system. In addition, students should use self-testing as a study strategy in preparing for their classes.

Now, having begun with an inflammatory claim – we need more testing in education – let us explain what we mean and back up our claims. First, we are not recommending increased use of standardized tests in education, which is usually what people think of when they hear the words “testing in education.” Rather, we have in mind the types of assessments (tests, essays, exercises) given in the classroom or assigned for homework. The reason we advocate testing is that it requires students to retrieve information effortfully from memory, and such effortful retrieval turns out to be a wonderfully powerful mnemonic device in many circumstances.

Tests have both indirect and direct effects on learning (Roediger & Karpicke, 2006b). The indirect effect is that, if tests are given more frequently, students study more. Consider a college class in which there is only a midterm and a final exam compared to a similar class in which weekly quizzes are given every Friday, in addition to the midterm and the final. A large research program is not required to determine that students study more in the class with weekly quizzes than in the class without them. Yet tests also have a direct effect on learning; many studies have shown that students’ retrieval of information on tests greatly improves their later retention of the tested material, either compared to a no-intervention control or even compared to a control condition in which students study the material for an equivalent amount of time to that given to students taking the test. That is, taking a test on material often yields greater gains than restudying material, as we document below. These findings have important educational implications, ones that teachers and professors have not exploited.

In this chapter, we first report selectively on findings from our lab on the critical importance of testing (or retrieval) for future remembering. Retrieval is a powerful mnemonic enhancer. However, testing does not lead to improvements under all possible conditions, so the remainder of our chapter will discuss qualifications and boundary conditions of test-enhanced learning, as we call our program (McDaniel, Roediger, & McDermott, 2007b). We consider issues of test format in one section, such as whether multiple-choice or short answer tests produce greater enhancements in performance. Another critical issue, considered in the next section, is the role of feedback: When is it helpful, or is it always helpful? We then discuss how to schedule tests and whether tests should occur frequently with short spacings between them – should we strike memory again when the iron is hot, as it were? Or should tests be spaced out in time, and, if so, how? In the next section, we ask if true/ false and multiple-choice tests can ever have negative influences on learning. These tests provide students with erroneous information, either in the form of false statements (in true/false tests) or plausible alternatives that are nearly, but not quite, correct (in multiple-choice tests). Might students pick up misinformation from these kinds of tests, just as they do in other situations (e.g., Loftus, Miller, & Burns, 1978)? We then turn to the issue of metacognition, and examine students’ beliefs and practices about testing and how they think it compares to other study strategies. Finally, we discuss how the findings on testing reviewed in this chapter might be applied in the classroom, as recent studies show that test-enhanced learning works in actual classrooms from middle school to college. We end with a few reflections on the role of testing in enhancing educational attainment.

TEST-ENHANCED LEARNING

Psychologists have studied the effects of testing on later memory, off and on, for 100 years (Abbott, 1909). In this section we report two experiments from our own lab to illustrate the power of testing to readers who may not be familiar with this literature and to blunt one main criticism of some testing research (see Roediger & Karpicke [2006b] for a thorough review).

Consider first a study by Wheeler and Roediger (1992). As part of a larger experiment, students in one condition studied 60 pictures while listening to a story. The subjects were told that they should remember the pictures, because they would be tested on the names of the pictures (which were given in the story). The test was free recall, meaning that students were given a blank sheet of paper and asked to recall as many of the items as possible. After hearing the story, one group of students was permitted to leave the lab and asked to return 1 week later for the test. A second group was given a single test that lasted about 7 minutes. A third group was given three successive tests. That is, a minute after their first test, they were given a new blank sheet of paper and asked to recall as many of the 60 pictures as they could for a second time. After they were finished, the procedure was repeated a third time. The group that was given a single recall test produced 32 items on the test; the group that took three tests recalled 32, 35 and 36, respectively. The improvement in recall across repeated tests (even though each later test is further delayed from original study) is called hypermnesia. However, the real interest for present purposes is how students performed on a final test a week later. All subjects had studied the same list of pictures while listening to a story, so the only difference was whether they had taken 0, 1 or 3 tests just after the study phase of the experiment.

The results from the 1-week delayed test are shown in Figure 1.1. Subjects who did not take a test during the first session recalled 17 items, those who had taken one test recalled 23 items, whereas those who had taken three tests recalled 32 items. The number of tests given just after learning greatly affected performance a week later; three prior tests raised recall over 80% relative to the no-test condition (i.e., (32 - 17)/17 × 100). Looked at another way, immediately after study about 32 items could be recalled. If subjects took three tests just after recall, they could still recall 32 items a week later. The act of taking three tests essentially stopped the forgetting process in its tracks, so testing may be a mechanism to permit memories to consolidate or reconsolidate (Dudai, 2006).

Figure 1.1 Number of pictures recalled on a 1-week delayed test, adapted from Table 1.1 in Wheeler and Roediger (1992). The number of tests given just after learning greatly affected performance a week later; three prior tests raised recall over 80% relative to the no-test condition, and the act of taking three tests virtually eliminated the forgetting process.

Critics, however, could pounce on a potential flaw in the Wheeler and Roediger (1992) experiment just reported. Perhaps, they would carp, repeated testing simply exposes students to information again. That is, all “testing” does is allow for repeated study opportunities, and so the testing effect is no more surprising than the fact that when people study information two (or more) times they remember it better than if they study it once (e.g., Thompson, Wenger, & Bartling, 1978). This objection is plausible, but has been countered in many experiments that compared subjects who were tested to ones who spent the same amount of time restudying the material. The consistent finding is that taking an initial test produces greater recall on a final test than does restudying material (see Roediger & Karpicke, 2006b). Here we report only one experiment that makes the point.

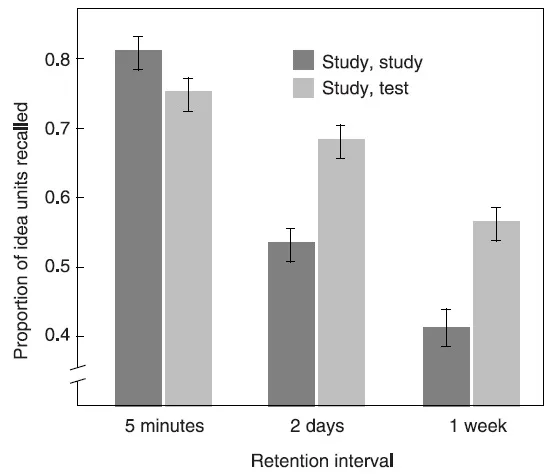

Roediger and Karpicke (2006a, Experiment 1) had students read brief prose passages about a variety of topics, many having to do with science (“The Sun” or “Sea Otters”) and other topics. After reading the passage, students either took a 7-minute test on the passage or read it again. Thus, in one condition, students studied the passage twice, whereas in the other they studied it once and took a test. The test consisted of students being given the title of the passage and asked to recall as much of it as possible. The data were scored in terms of the number of idea units recalled. The students taking the test recalled about 70% of the idea units during the test; on the other hand, students who restudied the passage were of course exposed to all the ideas in the passage. Thus, students who reread the passage actually received a greater exposure to the material than did students who took the test. The final test on the passages was either 5 minutes, 2 days or 7 days later, and was manipulated between subjects.

The results are shown in Figure 1.2 and several notable patterns can be seen. First, on the test given after a short (5-minute) delay, students who had repeatedly studied the material recalled it better than those who had studied it once and taken a test. Cramming (repeatedly reading) does work, at least at very short retention intervals. However, on the two delayed tests, the pattern reversed; studying and taking an initial test led to better performance on the delayed test than did studying the material twice. Testing enhanced long-term retention. Many other experiments, some of which are discussed below, have reported this same pattern (see Roediger & Karpicke, 2006b, for a review).

The results reviewed above, along with many others dating back over a century, establish the reality of the testing effect. However, not all experiments reveal testing effects. In the sections below, we consider variables that modulate the magnitude of the testing effect, beginning with the format of tests.

Figure 1.2 Results from Roediger and Karpicke (2006a, Experiment 1). On the 5-minute delayed test, students who had repeatedly studied the material recalled it better than those who had studied it once and taken a test. Cramming (repeatedly reading) does work, at least at very short retention intervals. However, on the two delayed tests, the pattern reversed; studying and taking an initial test led to better performance on the delayed test than did studying the material twice.

THE FORMAT OF TESTS

The power of testing to increase learning and retention has been demonstrated in numerous studies using a diverse range of materials; but both study and test materials come in a multitude of formats. Although the use of true/false and multiple-choice exams is now commonplace in high school and college classrooms, there was a time (in the 1920s and 1930s) when these kinds of exams were a novelty and referred to as “new-type,” in contrast to the more traditional essay exams (Ruch, 1929). Given the variety of test formats, one question that arises is whether all formats are equally efficacious in improving retention. If we want to provide evidence-based recommendations for educators to utilize testing as a learning tool, it is important to ascertain if particular types of tests are more effective than others.

In a study designed to examine precisely this issue, Kang, McDermott, and Roediger (2007) manipulated the formats of both the initial and final tests – multiple-choice (MC) or short answer (SA) – using a fully-crossed, within-subjects design. Students read four short journal articles, and immediately afterwards they were given an MC quiz, an SA quiz, a list of statements to read, or a filler task. Feedback was given on quiz answers, and the quizzes and the list of statements all targeted the same critical facts. For instance, after reading an article on literacy acquisition, students in the SA condition generated an answer to “What is a phoneme?” (among other questions), students in the MC condition selected one of four possible alternatives to answer the same question, and students in the read-statements condition read “A phoneme is the basic sound unit of a language.” This last condition allowed the effects of testing to be compared to the consequences of focused re-exposure to the target information (i.e., similar to receiving the test answers, without having to take the test). This control condition was a very conservative one, given that students in real life generally do not receive the answers to upcoming exams. A more typical baseline condition (i.e., having a filler task after reading the article) was also compared to the testing and focused rereading conditions. Three days later, subjects took a final test consisting of MC and SA questions.

Figure 1.3 shows that final performance was best in the initial SA condition. The initial MC condition led to the next best performance, followed by the read-statements condition and finally the filler-task condition. This pattern of results held for both final MC and final SA questions. Final test scores were significantly worse in the filler-task condition than the other three conditions, indicating that both testing (with feedback) and focused reexposure aid retention of the target information. Importantly, only the initial SA condition produced significantly better final performance than the readstatements condition; the initial MC and read-statements conditions did not differ significantly. Retrieval is a potent memory modifier (Bjork, 1975). These results implicate the processes involved in actively producing information from memory as the causal mechanism underlying the testing effect. Regardless of the format of the final test, the initial test format that required more effortful retrieval (i.e., short answer) yielded the best final performance, and this condition was significantly better than having read the test answers in isolation.

Figure 1.3 Results from Kang, McDermott, and Roediger (2007). Regardless of the format of the final test, the initial test format that required more effortful retrieval (i.e., the SA condition) yielded the best final performance, which was significantly better than being given the test answers without having to take a test. Although taking an initial MC test did benefit final performance relative to the filler-task control condition, the boost was not signifi-cantly above the read-statements condition.

Similar results from other studies provide converging evidence that effortful retrieval is crucial for the testing effect (Carpenter & DeLosh, 2006; Glover, 1989). Butler and Roediger (2007), for example, used art history video lectures to simulate classroom learning. After the lectures, students completed short answer or multiple-choice tests, or they read statements as in Kang et al. (2007). On a final SA test given 30 days later, Butler and Roediger found the same pattern of results: (1) retention of target facts was best when students were given an initial SA quiz, and (2) taking an initial MC test produced final performance equivalent to reading the test answers (without taking a test). As discussed in a later section of this chapter, these findings have been replicated in an actual college course (McDaniel, Anderson, Derbish, & Morrisette, 2007b).

Although most evidence suggests that tests that require effortful retrieval yield the most memorial benefits, it should be noted that this depends upon successful retrieval on the initial test (or the delivery of feedback). Kang et al. (2007) had another experiment identical to the one described earlier except that no feedback was provided on the initial tests. Without corrective feedback, final test performance changed: the initial SA condition yielded poorer performance than the initial MC condition. This difference makes sense when performance on the initial tests is considered: accuracy was much lower on the initial SA test (M = .54) than on the initial MC test (M = .86). The beneficial effect of testing can be attenuated when initial test performance is low (Wenger, Thompson, & Bartling, 1980) and no corrective feedback is provided.

This same conclusion about the role of level of initial performance can be drawn from Spitzer’s (1939) early mega-study involving 3605 sixth-graders in Iowa. Students read an article on bamboo, after which they were tested. Spitzer manipulated the frequency of testing (students took between one and three tests) and the delay until the initial test (which ranged from immediately after reading the article to 63 days later). Most important for present purposes is that the benefit of prior testing became smaller the longer one waited after studying for the initial test; i.e., performance on the initial test declined with increasing retention interval, reducing the boost to performance on subsequent tests. In a similar vein, it has been shown that items that elicit errors on a cued recall test have almost no chance of being recalled correctly at a later time unless feedback is given (Pashler, Cepeda, Wixted, & Rohrer, 2005). In other words, learning from the test is handicapped when accuracy is low on the initial test (whereas this problem does not occur with rereading, where there is re-exposure to 100% of the target information). For the testing effect to manifest itself fully, feedback must be provided if initial test performance is low. Recent research showing that retrieval failure on a test (i.e., attempting to recall an answer but failing to) can enhance future encoding of the target information (Kornell, Hays, & Bjork, 2009; Richland, Kornell & Kao, 2009) emphasizes further the utility of providing feedback when initial test performance is poor.

A recent study (Agarwal, Karpicke, Kang, Roediger, & McDermott, 2008) delved more deeply into the issue of whether the kind of test influences the testing effect. In a closed-book test, students take the test without having concurrent access to their study materials, and this is the traditional way in which...