![]()

1

CULTURAL AND CEREMONIAL BACKGROUND TO THE NORTH EUROPEAN MEGALITHS

Before the advent of agriculture, northern Europe was a land of hunter-gatherers. The process of transition here, from hunting-gathering to farming, was part of a much wider development that was taking place over the vast area of north-western Europe. Through their agricultural practices, the farmers altered the natural landscape in which they lived: forests were cut to create land suitable for crop fields, meadow pastures and settlements, and natural resources were transformed into economically and socially beneficial goods. Their most powerful and lasting legacy, however, was achieved not so much through agricultural practices but rather through the creation of a rich ceremonial landscape – a theatrical setting for social interaction and for expression, through rituals on a scale never encountered before, of the cosmological principles that shaped their vision of the universe in which they lived.

The most enduring testimony of that distant world view is offered by the megalithic tombs which, in the earlier part of the fourth millennium BC, the northern farmers built across the land in their thousands. It is these tombs, set within the context of the wider ceremonial landscape, that are the subject of this work. However, megaliths in northern Europe began to be built only after the first farming communities were fully established across the area. Even more importantly, they emerged on the scene after the early farmers had already developed a taste for expressing some of their ideas about the world through other ceremonial structures, namely the long barrows. These, although not built of such enduring materials, created architecture which was monumental not only in size but also in its conception, and thus they prepared the way for the subsequent feats in stone. By way of setting the appropriate scene this chapter therefore discusses, however briefly, first the culture and then the earliest monumental creations of the north European farmers.

The TRB culture

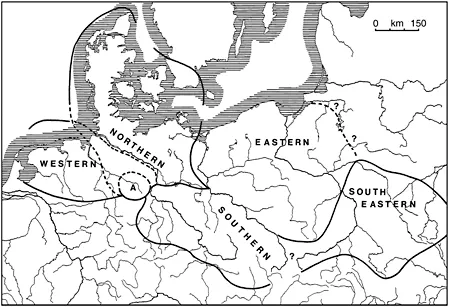

The megalithic tombs in northern Europe were created by communities which, in the archaeological literature, are known under the name of the TRB culture (from the German name Trichterrandbecher for one of the most characteristic vessel forms of the period, the funnel-necked beaker). The adoption of farming economy in northern Europe began, along the southern fringes of the north European plain, some time during the middle of the fifth millennium BC. At least half a millennium separated these first indigenous attempts and the final appearance of farming in southern Scandinavia. In its final extent, the distribution of the TRB culture was vast – from the Netherlands in the west to south-eastern Poland in the east, and from Bohemia and Moravia in the south to southern Scandinavia in the north – and several regional groups are recognised, which differ slightly from one another in details of material culture as well as chronology (Figure 1.1).

The idea of large-scale colonisation by central European Danubian farmers migrating from the south is no longer supported, and it is generally assumed that hunter-gatherers themselves adopted agriculture, although this does not exclude the movement of individuals as well as smaller communities. While the considerable degree of continuity with the preceding period is important, nevertheless many aspects of everyday life were given a new content and symbolism, not just in terms of novel economy but also, significantly, in the transformations within cultural, social and ideological spheres. In order to illustrate some of these phenomena, we may briefly consider aspects of settlement, economy and industrial developments, all of which demonstrate the originality and profundity of this historically momentous process.

The chronology of the TRB culture

The relative chronology of the TRB culture is based primarily upon the analysis of ceramic styles and is well established in all regions (see Midgley 1992, Chapter 4, for a detailed discussion of typo-chronology). The difficulties in establishing the absolute chronology result from the small number of radiocarbon dates, especially those in the transitional and early stages of the culture, as well as from the complexities of calibration.

In absolute terms the emergence of the TRB culture in its core area, which stretches from Kujavia in Poland to Lower Saxony in Germany, is dated to 4500/ 4400 BC, and it took at least half a millennium to manifest itself in southern Scandinavia. Dates from the area of Schleswig-Holstein suggest the presence of the TRB from about 4200–4100 BC onwards, and in Scandinavia a little later, from about 4000–3900 BC. The end of the TRB culture, some time between 2900 and 2700 BC, was as complex a process as its emergence. Within the broad north European context, the TRB culture was succeeded by the new cultural complex of the Corded Ware, although the situation is complicated in regional terms by the presence of smaller cultural groups such as the Globular Amphora culture on the north European plain and the Pitted Ware culture in southern Scandinavia.

Within this overall chronological framework the burials in flat graves and in monumental long barrows belong to the earliest horizon, beginning around 4400 BC on the north European plain and from about 3900 BC in Scandinavia; they continue in use until the end of the EN (Early Neolithic in the Scandinavian nomenclature), with

flat graves being in use throughout the entire TRB culture. The earliest dolmens contain pottery belonging to the EN II (the earliest dated dolmen is from Rastorf in Schleswig-Holstein, c. 3700/3500 BC) and the youngest materials belong to the MN I/MN II ceramic horizon. None of the passage graves contain materials older than MN I, and they continued to be built throughout MN II. Although there is some indication that the passage graves in the Falbygden area of central Sweden might have been built as early as 3500 BC (Persson and Sjögren 1996) the traditional view places most passage graves somewhat later, at around 3300 BC.

TRB settlement and land use

The early farmers in northern Europe chose to settle upon light soils, placing their settlements in undulating landscapes which were interspersed with boggy and marshy areas and stretches of open water. This choice of topography underlined the significance of the dry higher landscape and the low-lying wetter ground; it offered ecological diversity in which the forest, meadow and arable land created conditions suitable for early agriculture but also facilitated the traditional exploitation of wild resources.

Once fully established, the economy of the TRB culture was based on mixed farming, although these resources may have been taken up at varying rates and in accordance with regional climatic and ecological conditions. Cereals of various types (wheats and barley), leguminous plants such as peas and beans, and flax are known from all regions of the TRB culture, although barley seems to have been particularly suited to the cooler climatic conditions of southern Scandinavia. Domesticated animals – cattle, pigs, sheep and goats – were an important source of food in the form of meat and dairy produce, and of raw materials, providing hides, wool and bone for tool manufacture. In the case of oxen, pulling power was becoming economically important, and undoubtedly their ownership also enhanced the social position of individuals and small communities.

Traditional exploitation of wild resources – hunting of game, fishing and fowling – continued alongside agricultural activities throughout the TRB, with farmers making good use of the hunting and fishing stations established along lakes, rivers and coasts during the Late Mesolithic. The lake belt across the north European plain provided a favourable environment for fowling and freshwater fishing, and the forests were abundant in deer, bison, wild boar and a range of smaller animals. Forests and river meadows also provided seasonal edible plants and fungi, as well as various wild fruits which, although rarely attested in the archaeological record, must have been gathered to provide medicines and add nourishment to the daily diet.

In the coastal regions, on the Baltic and along the North Sea, seals, migratory birds and deep-sea fish continued to be caught, and the Mesolithic shell-middens demonstrate that marine shellfish – oysters, cockles and periwinkles – were still collected as important nutritional supplements. Bones of wild animals provided suitable raw materials for manufacture of tools, and the continued, if somewhat diminished, importance of wild animal teeth, boars’ tusks and fish vertebrae in the crafting of ornaments suggests that hunting was still an important social pursuit, providing opportunities for gaining prestige and experience outside the ordinary quotidian sphere.

Against the background of the solidity and permanence of the megalithic chambers, the archaeological record with respect to the actual settlement sites is ambiguous. Early TRB settlements generally appear small and of relatively short-lived duration, although this view may to some extent be influenced by the excavation strategies, especially at sites only partially preserved under later monuments such as the Neolithic or Bronze Age mounds. Such seems to have been the case at Sarnowo in Kujavia, where small rectangular houses have been found preserved under the long mounds, although the settlement does seem to have shifted to a higher and drier location by the time the cemetery was being constructed. Similar finds are known from Denmark, for example light buildings found underneath the mounds of Mosegården in Jutland or Lindebjerg on Zealand.

However, recent rescue excavations in western Sweden suggest that we may have underestimated the scale of some of the early sites. At Saxtorp 23, in western Scania, an area of 15,000 m2 was settled, with clear division of space for dwellings, wells, industrial pits and even burials; while at Dagstorp, another site nearby, there were at least two long houses (of the so-called Mossby type, after a settlement on the south coast of Scania).

Indeed this type of house, long with rounded gable ends and central roof-bearing posts, is now commonly identified on the EN Scandinavian sites and may well represent a characteristic form of early TRB dwelling in this region. Such structures are known from the early phase at Limensgård on the island of Bornholm – the settling of which must have posed a considerable challenge to the early farmers – at Mossby itself and at Dagstorp in Scania, Slottsmöllan and Hästhagen in Halland, and Ornehus on east Zealand. They vary in length from 12 to 18 m and are usually between 5 and 6 m wide. The sites also contain, scattered in between the houses, large numbers of pits full of domestic debris, suggesting that many activities may have taken place outside the actual dwellings. Similar oval houses are known from Lower Saxony, at Wittenwater and Engter (P. O. Nielsen 2004; Andersson 2004; Malmer 2002).

The later TRB settlements display a somewhat different character. Although house structures continue to be elusive, some of the sites can be quite large; thus settlement traces at Spodsbjerg on Langeland covered 300,000 m2, and at Bronocice in southern Poland the settlement spread out over an area 500,000 m2 in size. Indeed, in the later TRB some of the earlier ceremonial enclosures, such as Sarup, Siggersted, Hygind and Bundsø, became places of permanent or at least long-term settlement, with rich occupational traces.

The island of Bornholm continued to be occupied during the later TRB, and long houses up to 22 m in length are known from Limensgård and Grødbygård. They appear to have been sturdier than the EN houses, with foundation trenches on at least three sides. The overlap of many of the Grødbygård houses suggests that perhaps only two or three buildings were contemporary (P. O. Nielsen 1999). Further evidence from this island comes from Vasagård and Rispebjerg (Kaul et al. 2002). Vasagård became a large settlement, twice the size of the original EN causewayed enclosure, protected by a double timber palisade. Although there was a large amount of typical domestic debris, certain structures – for instance circular features defined by post holes – as well as the character of some deposits (burnt flint) suggest that cults and rituals continued here alongside quotidian activities. Rispebjerg appears to have been an even more complex site, with at least 14 palisades, the outermost enclosing an area six hectares in size.

That palisaded settlements were quite common in the later TRB is also demonstrated by a number of other Scandinavian sites, for example at Sigersted and Spodsbjerg in Denmark, and Dösjebro near Malmö in Scania (P. O. Nielsen 2004; Svensson 2004). Palisaded sites may suggest a need for a degree of protection, especially in areas where other cultural groups (such as the early Corded Ware) may have been engaged in economic and social competition. The ultimate burning of the palisade at the Dösjebro settlement – a site strategically placed at the confluence of two rivers – although it post-dates the TRB occupation, may be indicative of socially unstable times.

Although houses continue to be elusive on some of these large settlements, once again the Scanian evidence provides some indications of the layout of settlement sites. Thus during the MN period at Dagstorp one rectangular and four trapezoidal houses (some divided into individual rooms) were built side by side, clearly in simultaneous use. Other structures, identified through post holes in between the houses, could represent workshops in small huts or protected by temporary windbreaks, as they contained large amounts of flint and pottery (Andersson 2004, 169).

The 1938–40 excavations at the ...